In honour of Yom Ha’Atzmaut this week—Israel’s Independence Day—let’s take a journey back into the ancient and little-known early history of Zionism. In the past, we have already explored how the Zionist movement did not begin with secular Jews in the late 19th century, as is commonly thought, but decades earlier with religious Jews. In fact, the history of Zionism dates back even further when we properly define Zionism simply as a movement to restore the Jewish people to their ancestral homeland. This did not begin in modern times, but all the way back in the 1st century. As soon as the Romans had destroyed the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE and exiled a large majority of Jews, there has been a deep yearning to return to the Holy Land and rebuild.

The first such “proto-Zionist” movement was that of Shimon bar Kochva (d. 135 CE). Shimon is believed to have hailed from the small Judean town of Koziba, and was originally referred to as Shimon bar Koziba. The Emperor Hadrian made plans to flatten Jerusalem and rebuild it as Aelia Capitolina, with a shrine to Jupiter on the Temple Mount. Jews were understandably incensed. Bar Koziba managed to organize and train a group of Jewish rebels that miraculously succeeded in expelling the Roman forces from the Holy Land. They cleared the Temple Mount and even began construction of a new Holy Temple. Jews started returning to Israel, and it appeared that the ancient prophecies were beginning to be realized.

The first such “proto-Zionist” movement was that of Shimon bar Kochva (d. 135 CE). Shimon is believed to have hailed from the small Judean town of Koziba, and was originally referred to as Shimon bar Koziba. The Emperor Hadrian made plans to flatten Jerusalem and rebuild it as Aelia Capitolina, with a shrine to Jupiter on the Temple Mount. Jews were understandably incensed. Bar Koziba managed to organize and train a group of Jewish rebels that miraculously succeeded in expelling the Roman forces from the Holy Land. They cleared the Temple Mount and even began construction of a new Holy Temple. Jews started returning to Israel, and it appeared that the ancient prophecies were beginning to be realized.

The greatest sage of the day, Rabbi Akiva, believed Koziba to be the potential messiah of the generation, and even declared him as the new king of Israel (see Yerushalmi Ta’anit 24a). He applied to him the verse in the Torah that a “A star shall emerge out of Jacob” (Numbers 24:17), hence the nickname Bar Kochva, “son of a star”. Unfortunately, Bar Kochva became something of a dictator and even ended up killing one of the leading sages, Elazar haModai, in a fit of rage. The Romans returned with superior forces and crushed the rebellion. Rabbi Akiva and his 24,000 students tragically perished in the war as well (as explored in depth in this week’s shiur). Bar Kochva was renamed Bar Koziva, “son of a lie”.

Interestingly, Israeli archaeologist Yigael Yadin found evidence that Bar Kochva had sought to restore Hebrew as the primary spoken language in Israel at the time, and made it the official language of his short-lived kingdom. Recall that in those days the vernacular in Israel was Aramaic (followed by Greek). Hebrew was reserved only for the sacred. This is another way in which Bar Kochva pre-empted modern Zionism.

It is worth noting that it was after the Bar Kochva Revolt when the term “Palestine” was first used officially. The Romans had suffered massive casualties, and were fed up by yet another Jewish revolt, so they decided to obliterate Judea off the face of the Earth. They renamed the province to “Palestine”—after the Biblical enemies of the Israelites, the Philistines—and redrew the boundaries so that it was no longer an independent province but attached to Syria, creating the province of Syria-Palestina.

Nehemiah’s Rebellion

In the early 7th century CE, Israel was under the control of the Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire. The Byzantines often warred with Sassanian Persia, where the majority of Jews lived at the time. A Jewish military captain named Nehemiah ben Hushiel (possibly the son of the Reish Galuta, the “Exilarch” who was the official government-appointed liaison to the Jewish people) commanded a “Jewish legion” for the Persians. In 614 CE, the legion was able to recapture Jerusalem from the Byzantines. Like Bar Kochva before him, Nehemiah cleared the Temple Mount and began plans for rebuilding the Temple. Jews slowly started to stream back to Israel. Nehemiah also began a search for legitimate lines of kohanim to re-establish Temple services. His works were greatly assisted and funded by a wealthy Jew named Benjamin of Tiberias.

It wasn’t long before Jerusalem’s Christians revolted, and soon after the Persians betrayed the Jews, leading to a Byzantine recapture of the city. According to some sources, the Jews continued to resist for a long time, until 628 CE. Eventually, most of the Jewish inhabitants, including Nehemiah, were executed. Ironically, it was this event that severely weakened Byzantine control over the area, opening the door for the Muslim armies to take over just a few years later in 634 CE.

Although this episode of Jewish history is little-known and oft-forgotten, historians today believe it had a large impact on Judaism, and on Jewish texts. Some say the wicked Byzantine ruler who put down the revolt, Heraclius I, inspired the figure of “Armilus” in later Jewish apocalyptic writings. Others might argue that Jews at the time already expected an anti-messianic Armilus figure, and simply identified Heraclius as that Armilus.

Rebuilding Israel from the 16th Century

In the 12th century, Menachem ben Solomon of Baghdad inspired a proto-Zionist movement and gathered a group of Jews to head back to Jerusalem and rebuild. He renamed himself David Alroy and claimed to be Mashiach. The Sultan arrested him, and Alroy managed to escape (miraculously, according to legend). He led an uprising that was successful for a short time, based in Amadiya. Though his rebellion was quashed, he inspired groups of Jews to head back to their ancestral homeland, and for decades afterwards there were still a small group of “Menachemites” that continue to believe in his messiahship.

A far more successful attempt was made by Dona Gracia Mendes (1510-1569). She was born to a family of Sephardic conversos (those forcibly converted to Christianity by the Inquisition), and married a banker. When he passed away, she took over the banking business and grew it to new heights, at one point becoming the most powerful woman in Europe, if not the world. She organized an “underground railroad” to help those Jews forcibly-converted to escape the Inquisition and settle in free lands, where they could return to their true faith. Mendes herself ended up settling in Istanbul where she could freely express her Judaism once more. She began to heavily finance synagogues, yeshivas, and Jewish infrastructure across the Ottoman Empire.

More significantly, Mendes had a vision of re-establishing an independent Jewish state in the Holy Land, free of persecution. In 1558, she managed to secure a lease from the Sultan to resettle and rebuild Tiberias. She revived the ancient Jewish town and settled many Jewish refugees there. Her nephew, Don Joseph Nasi (1524-1579) continued her work and went on to be granted the official title “Lord of Tiberias”. He expanded the lease to cover more of the Holy Land, and began planting the seeds of an independent Jewish state in Israel. Many historians consider Dona Gracia and Don Joseph as the first true “proto-Zionists”. Their work also helped to make Tzfat the flourishing Jewish town that it soon became: the “capital” of Kabbalah and the place where the Jewish code of law, the Shulchan Arukh, was composed, along with the revolutionary mystical teachings of the Ramak (1522-1570) and the Arizal (1534-1572), not to mention popular hymns like Lecha Dodi.

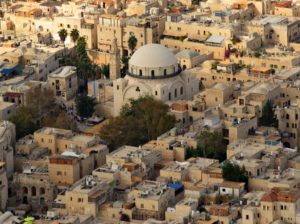

Now that the Holy Land was habitable again, more Jews started to return. In the late 1600s, Yehudah Segal of Moravia, known as “Yehuda haHasid” (not to be confused with the Yehuda haHasid of the 12th century) convinced 31 families to come with him to Israel. Along their journey, they gathered more Jews yearning to make aliyah, and eventually numbered 1500 migrants. After a long and arduous trip which took the lives of nearly a third of the group, they finally arrived in Jerusalem in 1700. It was this group that first built what is now known as the Hurva Synagogue, twice destroyed and rebuilt, and currently the largest Jewish dome in the Jerusalem skyline.

Many more groups of Jews from Europe followed, including both Hasidim and Mitnagdim (those who initially opposed the Hasidic movement). The founder of Hasidism himself, the Ba’al Shem Tov, sought to make aliyah, but was thwarted. The students of the Vilna Gaon (1720-1797) settled successfully, first arriving on the 5th of Iyar which later happened to become Yom Ha’Atzmaut, a spiritual coincidence whose significance was explored here. Disciples of the Mitteler Rebbe (1773-1827), the second rebbe of Chabad, settled in Hebron around 1815. Around the same time, a prominent Moroccan-American Jew named Moses Yulee Levy (1782-1854) sought to establish a Jewish state in Israel. He ended up instead buying 50,000 acres in Florida to build a “New Jerusalem” refuge for Jews. His contemporary, Mordechai Noah (1785-1851), similarly bought land near Buffalo to establish the “Ararat” refuge for Jews in 1825. When the project failed, he realized a Jewish state could only succeed in Israel, and devoted the rest of his life to that cause.

Finally, one of the most fascinating proto-Zionist stories is that of Warder Cresson (1798-1860). He was a deeply religious Quaker and in 1844 became America’s first consul in Jerusalem. Inspired by Jerusalem’s Jewish community, he ended up circumcising and converting to Judaism, taking on the name Michael Boaz Israel. In 1852, he established one of the first modern agricultural colonies in the Holy Land, long predating the kibbutzim. Some years earlier, a Hasidic Jew named Israel Bak (1797-1874) established an agricultural colony near Tzfat, where he also established the first modern printing press in the Holy Land. He was one of the key inspirations for Sir Moses Montefiore (1784-1885) to invest heavily in Israel, setting the foundations for the State of Israel.

All of these great individuals predated Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), who did not launch the Zionist movement (contrary to popular belief) and actually passed away at a young age with minimal progress yet having been made. Nonetheless, Herzl managed to inspire a lot more people, particularly secular people, to join all the religious pioneers that had already done so much to set the stage. Herzl gave the necessary push for a ball that had already been rolling for centuries. (He is specifically credited with founding Political Zionism.) And there were many more key figures after him without whom the State of Israel would have never materialized. All of these people should be celebrated and remembered on Yom ha’Atzmaut, as we mark 74 years of a renewed, thriving, independent, far-from-perfect-but-the-best-we’ve-got Jewish state in the Promised Land.

Chag Sameach!

Make your Shavuot all-night learning meaningful with

Tikkun Leil Shavuot – The Arizal’s Torah Study Guide

(15% off this week with code REACHOUT15)

Pingback: Blessings Through Curses | Mayim Achronim