One of the surprising things about the Torah is that it actually does not say much about spiritual matters, at least not on the superficial level. Adam is given a soul (Genesis 2:7) and all human beings subsequently have one, but there is no exposition on what a soul actually is. There is no discussion of the afterlife, either. In this week’s parasha, Va’etchanan, we are cautioned to “carefully guard our souls” (Deuteronomy 4:15). How exactly does one do so? We know that to keep the soul healthy, we need to fulfil mitzvot, yet mitzvot are mostly actions performed with the body. How does this connection between body and soul actually work? Moreover, our Sages use the above phrase in teaching that one is responsible for the health of their body as well. What is the difference between a healthy body and a healthy soul?

To begin, it is worth recalling the parable of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi to Antoninus (Sanhedrin 91a-b):

Antoninus said to Rebbi: “The body and the soul can both free themselves from judgment. The body can plead: ‘The soul has sinned, since from the day it left me, I lie like a dumb stone in the grave.’ While the soul can say: ‘The body has sinned, since from the day I departed from it, I fly freely in the air like a bird.’”

He replied: “I will tell you a parable. To what may this be compared? To a king who owned a beautiful orchard which contained splendid figs. Now, he appointed two watchmen, one lame and the other blind. [One day,] the lame man said to the blind: ‘I see beautiful figs in the orchard. Come and take me upon your shoulders, that we may procure and eat them.’ So the lame strode the blind, procured them, and they ate them. Some time after, the owner of the orchard came and inquired: ‘Where are those beautiful figs?’ The lame man replied, ‘Do I have feet to walk with?’ The blind man replied, ‘Do I have eyes to see with?’ What did [the king] do? He placed the lame upon the blind and judged them together. So will the Holy One, blessed be He, bring the soul, place it in the body, and judge them together…”

We see that there is an intricate connection between body and soul. In the parable above, the soul is like the lame man, unable to move in this world on its own. The body is the blind man who, though mobile, has no vision or direction. It is the lame man that makes the suggestion to the blind, and the blind that allows the suggestion to be fulfilled. Similarly, the soul powers the body which, in turn, commits the sin.

Now, the soul itself is pure, so how could it ever suggest sin, as the lame man did? To understand this, we must remember that “spiritual” is not necessarily synonymous with “good” or “pure”. There are two spiritual realms, one of holiness, and the “other side”, the Sitra Achra, of impurity, the source of evil. The Sitra Achra is the necessary counterweight to the side of holiness, for otherwise there would be no true free will. The Sitra Achra seeks to encapsulate everything holy in its kelipot, “husks” of impurity. While the soul itself is pure, the impure kelipot can surround it and suppress it. In that situation, there is improper communication between soul and body as the kelipot get in the way. For instance, the soul may be sending a message to seek enlightenment, but the signal is contaminated and the body may then seek “enlightenment” through dangerous drugs instead of through kosher means.

The soul wants to break free from all kelipot, and “fly free like a bird”. Fulfilling mitzvot breaks through the kelipot, while sinning only adds more layers. The more a person breaks through those husks, the more their soul is able to exude. A spiritual person is one who has broken through many or most of their kelipot and is therefore truly in-tune with their soul, and sensitive to the spiritual realities around them. (It is worth mentioning that many people today believe they are “spiritual” and in-tune, but often sense nothing more than the Sitra Achra!)

The body plays a key role, too, since the soul is attached to the body in this world. A weak body is a weak vessel, and a strong soul cannot be contained within it. Furthermore, a weak body is an easy target for kelipot to enter. It is therefore no wonder that our Sages described the forefathers and prophets as powerful men: Abraham battled five kings, Moses took on the giant Og, David and Samson were mighty heroes. The entire story arc of Jacob in the Torah is how a scrawny, fearful youth who “sat in tents” (Genesis 25:27) overcame a series of physical challenges and rose up to “battle gods and men and prevail”! (Genesis 32:29). Jacob is Israel, and his story is the story of our nation. This is one reason Rav Kook famously stated (in his Orot) that along with “spiritual glory”, Jews must have “healthy flesh and blood, strong and well-formed bodies, and a fiery spirit encased in powerful muscles.” Long before, our Sages made clear that two of the prerequisites for spiritual greatness is to be gibbor, “mighty” and a ba’al komah, having a strong physical “stature” (Shabbat 92a). So, the body needs to be worked on, strengthened, and kept in good health.

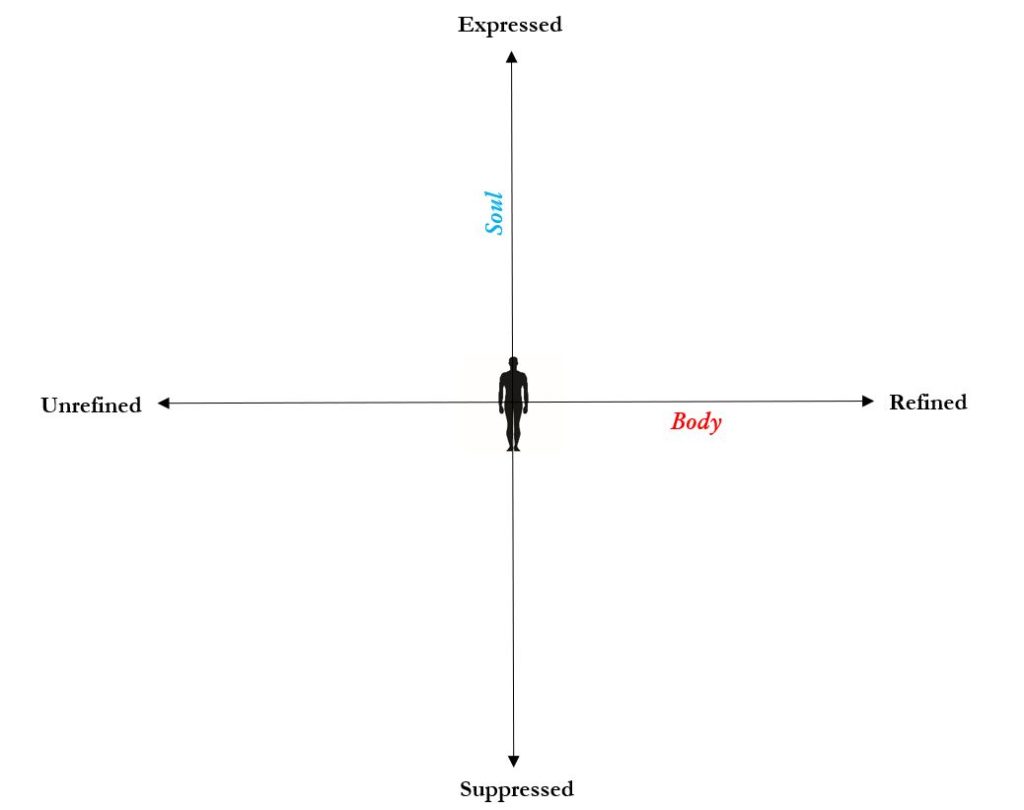

To put it all together, we can say that the soul is measured on a scale of expression, while the body on a scale of refinement. The soul itself is wholesome, unbounded, otherworldly. One cannot really “exercise” or “refine” their soul, since it is already pure (as we affirm each morning when we recite Elohai Neshamah); what one can do is express more or less of it. With the body, on the other hand, expression is not the issue. A person is essentially in full expression of their body most of the time, with minor exceptions. The body’s issue is that it is animalistic and instinctual, naturally greedy and self-absorbed. It is the body that drags the soul into sin. So, the body needs to be refined and improved upon. However, refining the body is more than just exercising and having a good diet. It is also about being in control of the body and its desires, which is the true definition of being gibbor. Today, society focuses on the external refinement of the body, but little on the internal refinement. On the contrary, the message out there is not to worry about internal refinement: Go ahead, indulge in the body’s desires as much as you like. Don’t bother trying to change your internal qualities or predispositions—that’s futile. The only thing worth working on is the external physique. And for that, society has a smorgasbord of cosmetics, steroids, and surgeries.

In reality, our mission is to refine the body to the greatest degree, externally and internally, to make it a fine vessel for the soul, a place where the soul can rest comfortably and express itself to the greatest degree. The body and soul, therefore, are deeply intertwined, and the success of one is inexorably tied to the success of the other. If we were to graph the relationship, we would start with something like this:

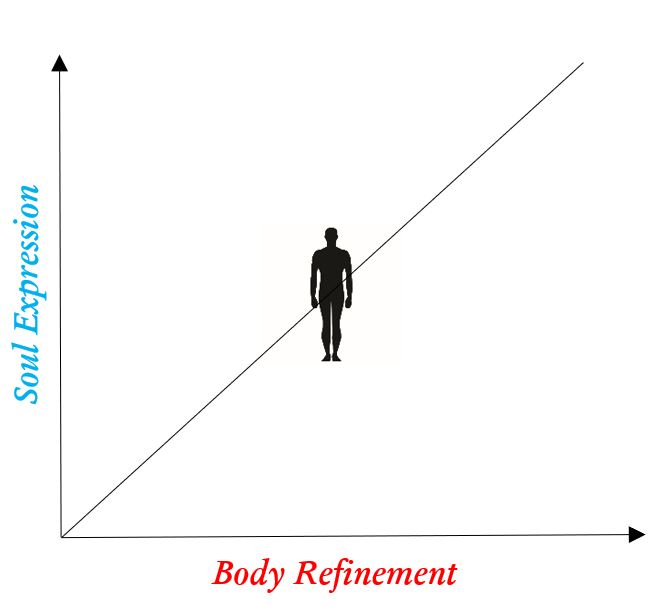

A person should strive to be in the top right corner. This is where the body is at its healthiest, and the soul at its peak expression. Generally speaking, we may think of the body-soul relationship as being linear, ie. the more refined the body, the more the soul can be expressed, and vice versa, like this:

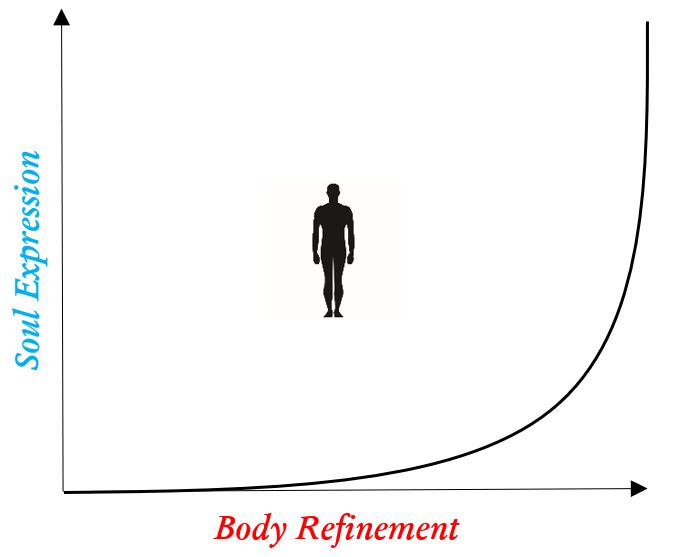

In truth, it is probably more of a geometric relationship, like this:

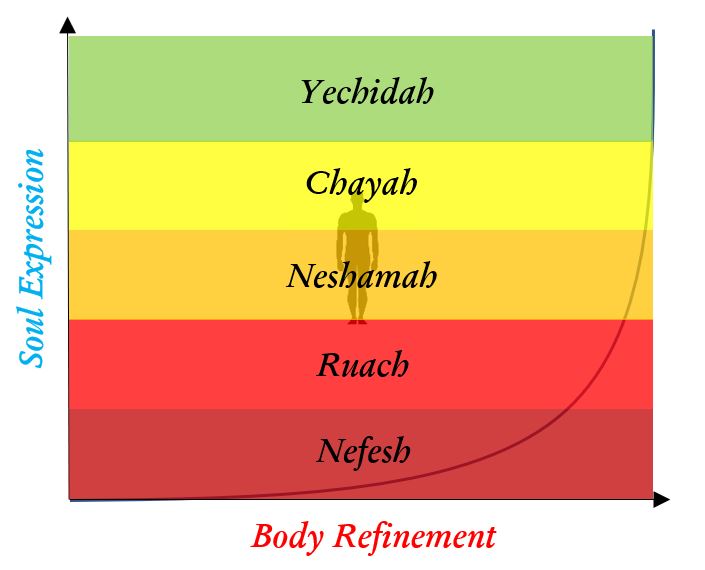

It takes a lot of refinement at first, with little spiritual gains. After a while (once the toughest kelipot have been shattered), the trend switches and the spiritual growth becomes dramatic. There is another important reason why this graph is more accurate. Since the body is finite, there is a limit to its refinement. The soul, on the other hand, is unlimited, and so the graph can continue going up endlessly, an asymptote that never quite reaches the end. We find that, as expected, 100% body refinement is not exactly possible (the frail, mortal body can never be perfect after all), but there is always room for evermore increases on the soul axis. Finally, we can add one more element to the graph, labelling the growth periods roughly according to the levels of soul:

Pingback: Stages of Spiritual Development | Mayim Achronim