This week’s parasha, Pinchas, begins by praising Pinchas, grandson of Aaron, for slaying the wicked Zimri and Cozbi, and describes God’s eternal reward to him. In the past, we have already explored in depth how Pinchas became Eliyahu. In addition to this, Kabbalistic texts note that smaller soul-sparks of Pinchas went to several other people in history. One of these people is the Talmudic sage Pinchas ben Yair, who is featured even more prominently in the Zohar. The Talmud seems to state that Pinchas ben Yair was the son-in-law of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, while the Zohar makes clear that he was his father-in-law. The contradiction has puzzled many in the past. How do we make sense of this, and what does the Biblical Pinchas have to do with it all?

The Zohar states in a few places that the three greatest mystics were Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (“Rashbi”), Rabbi Pinchas ben Yair, and Rabbi Elazar the son of Rabbi Shimon. In Zohar III, 203a, we are told that these three figures correspond to the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, respectively. So, Pinchas ben Yair is likened to Isaac. This is not just cosmetic. In Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, the “Book of Reincarnations”, Rabbi Menachem Azariah de Fano (1548-1620) points out that Isaac reincarnated in the Biblical Pinchas. In fact, the numerical values of their names are the same! (יצחק = 208 = פינחס) Of course, a spark of Pinchas then went to Pinchas ben Yair, completing the spiritual connection. The book also points out something even more fascinating:

Isaac’s main adversary in life was his half-brother Ishmael. The latter was eventually expelled from the home of Abraham so that he would no longer be a bad influence on Isaac. The Torah predicts that Ishmael would go on to become a “wild-ass” of a man (Genesis 16:12). Rabbi de Fano incredibly points out that to rectify his sins, Ishmael was literally reincarnated into a wild ass, a donkey, and this was the famous donkey of Pinchas ben Yair!

The Donkey of Pinchas ben Yair

The Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 60:8) tells the story of how the donkey of Pinchas ben Yair was once stolen by brigands. The donkey refused to eat their non-kosher food. After three days, the criminals gave up and let the donkey go, wishing to avoid a rotting donkey corpse. The donkey returned home and Pinchas ben Yair called out to have food brought out to the poor animal immediately, for he knew that his donkey did not eat anything for three days. The servants brought some barley, but the starving donkey refused to eat it! Pinchas ben Yair asked the servants if all the appropriate tithes had been separated, and it turned out that the produce was demai, meaning there was a slight uncertainty regarding a particular tithe. Truly, the barley was still kosher, but the donkey had taken on an extra stringency! Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot explains why the donkey was so special: it was actually Ishmael, who had to be extra stringent to make up for the many sins of his past life.

The Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 60:8) tells the story of how the donkey of Pinchas ben Yair was once stolen by brigands. The donkey refused to eat their non-kosher food. After three days, the criminals gave up and let the donkey go, wishing to avoid a rotting donkey corpse. The donkey returned home and Pinchas ben Yair called out to have food brought out to the poor animal immediately, for he knew that his donkey did not eat anything for three days. The servants brought some barley, but the starving donkey refused to eat it! Pinchas ben Yair asked the servants if all the appropriate tithes had been separated, and it turned out that the produce was demai, meaning there was a slight uncertainty regarding a particular tithe. Truly, the barley was still kosher, but the donkey had taken on an extra stringency! Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot explains why the donkey was so special: it was actually Ishmael, who had to be extra stringent to make up for the many sins of his past life.

The Midrash concludes with the later rabbis declaring that “if the early Sages were angels, we are merely humans; and if they were humans, we are merely donkeys”, to which Rav Mana counters: “We are not even donkeys” compared to the donkey of Pinchas ben Yair! This implies that Pinchas ben Yair was among the earlier generation of great Sages, a point that may help us in solving the Pinchas ben Yair father-in-law/son-in-law dilemma.

The problematic Talmud passage is in Shabbat 33b. It recounts how Pinchas ben Yair heard that Rashbi and Rabbi Elazar finally emerged from their many years of hiding in the cave. The phrasing there is that Pinchas ben Yair, chataney, “his son-in-law”, heard. This contradicts the multiple places in the Zohar where Pinchas ben Yair is described as Rashbi’s father-in-law. The solution can be found in the Ben Yehoyada of the Ben Ish Chai (1832-1909), in his commentary on the story that follows in the Talmud. Since Rashbi and Rabbi Elazar spent their time in the cave buried in the ground, learning Torah, their skin had become terribly parched and cracked. Pinchas ben Yair immediately took them to the bathhouse for healing.

The Talmud says that Pinchas was bathing Rashbi and tending to his wounds, crying over the suffering that Rashbi went through. Ben Ish Chai points out that a son should not bathe his father so as not to see him naked (something that we learn all the way back in the case of Noah and his sons following the Flood). The same rules of father and son apply to father-in-law and son-in-law. So, if Pinchas ben Yair was bathing Rashbi, it means he must have been his father-in-law, not son-in-law. (For obvious reasons, a father is allowed to bathe his child.)

Moreover, the Talmud continues that when Pinchas ben Yair cried, Rashbi responded that he should be happy, not sad, for his wounds were really the scars of his tremendous Torah learning in the cave. The Talmud concludes that initially, Rashbi would ask a question and Pinchas ben Yair would have 12 different answers for him, and henceforth, it was Pinchas ben Yair who would ask a question and Rashbi would have 24 different answers in return! The clear implication here is that Pinchas ben Yair was initially Rashbi’s teacher, and only after the cave experience had the disciple surpassed his master. Thus, Rashbi told his father-in-law to be happy that he merited to see his son-in-law attain such Torah greatness.

And so, we can confidently conclude that Pinchas ben Yair really was the father-in-law of Rashbi, as the Zohar says. When the Talmud says chataney in the passage above, it must be referring to Rashbi being the chatan. The reading should be that Pinchas ben Yair heard about his chatan, Rashbi. With this in mind, we can better understand another famous incident of that era.

Bar Kochva and the Messianic Age

As discussed many times in the past, Rashbi was one of the five main surviving students of Rabbi Akiva, who himself perished at the hands of the Romans during the Bar Kochva Revolt. At the time, Rabbi Akiva had declared Bar Kochva to be the presumptive messiah. If Rabbi Akiva did so, it means Bar Kochva was not a false messiah, but rather a failed messiah. Indeed, Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot says that Bar Kochva really did contain the spark of Mashiach ben Yosef. We know that Eliyahu is supposed to come first to herald the coming of Mashiach. So, who would have been the Eliyahu of that generation?

If Pinchas ben Yair is Rashbi’s father-in-law, that would make him a contemporary of Rabbi Akiva. He likely would have been among the rabbis that proclaimed Bar Kochva the presumptive messiah. And Pinchas ben Yair is the spark of Pinchas, who is Eliyahu! In that case, Pinchas ben Yair would have served as the Eliyahu of that generation. And this now allows us to better understand the most famous teaching of Pinchas ben Yair, in the final Mishnah of Sotah:

Pinchas ben Yair says: Alacrity [in the observance of mitzvot] leads to cleanliness, cleanliness leads to purity, purity leads to abstinence, abstinence leads to holiness, holiness leads to humility, humility leads to fear of sin, fear of sin leads to piety, piety leads to Ruach HaKodesh [divine inspiration], and Ruach HaKodesh leads to the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Resurrection of the Dead is initiated through Eliyahu, of blessed memory.

Pinchas ben Yair himself was on the highest levels of alacrity, holiness, and Ruach HaKodesh—the Eliyahu of his generation—and believed the time was ripe for the Messianic Age and the Resurrection of the Dead. Alas, it was not to be, but he left the foundation for the path to that Final Redemption. His Mishnah served as the basis for a similar statement given in his name in Avodah Zarah 20b:

Torah study leads to vigilance, vigilance leads to alacrity, alacrity leads to cleanliness, cleanliness leads to abstinence, abstinence leads to purity, purity leads to piety, piety leads to humility, humility leads to fear of sin, fear of sin leads to holiness, holiness leads to Ruach HaKodesh, Ruach HaKodesh leads to the Resurrection of the Dead…

This, in turn, served as the basis for Mesilat Yesharim, “Path of the Just”, the classic textbook for personal development and spiritual growth, composed by the great Ramchal (Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, 1707-1746). The book has become standard reading in the Jewish world today, and every individual now has the tools to ascend to the highest spiritual levels. Through this process, we will be able to usher in the Messianic Age and the Resurrection of the Dead, as Pinchas ben Yair intended long ago.

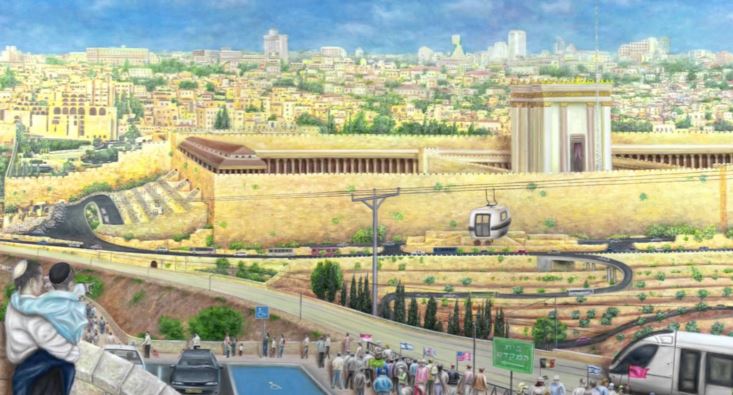

‘Going Up To The Third Temple’ by Ofer Yom Tov

*Note: for those who might point out that Pinchas ben Yair is also featured in stories together with Rabbi Yehuda haNasi, a later figure, this actually isn’t a problem. According to tradition, Rabbi Yehuda haNasi was born the same day that Rabbi Akiva died. Rashbi went into the cave some time after that, and 13 years later we know Pinchas ben Yair was still alive and well. At this point, Rabbi Yehuda would have already been in early adulthood. So, there is no reason why they cannot be featured in the same story!