‘Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem’ by Francesco Hayez (1867)

On Tisha b’Av we commemorate numerous tragedies in Jewish history, most notably the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem. The Tanakh outlines quite clearly the events that led to the destruction of the First Temple. When it comes to the Second Temple, however, little is generally spoken of even though we have a lot more historical information about what was going on at the time. We tend to greatly simplify things by reducing it to the same old adage that “the Temple was destroyed because of sinat chinam”, baseless hatred. How did the destruction of the Temple really come about? What were the events that led to the Great Revolt and the first Jewish-Roman War? And who, exactly, were those Jews that harboured such immense hatred for each other?

Casus Belli

At the end of the Second Temple era, Judea was under Roman rule and oppression. There was widespread negative sentiment against the Roman overlords. Abuse and rape by Roman soldiers was common. On several occasions, the Romans raided the Temple treasury and stole its wealth. Heavy taxation was another major issue, with many Jews refusing to pay anything to the idolatrous Romans. In fact, the Sages of the time went so far as to institute a minor holiday (on the 25th of Sivan) to commemorate when the Roman tax collectors were expelled! In Megillat Ta’anit, this holiday is listed as a happy date on which it is forbidden to fast.

Josephus (c. 37-100 CE) gives us a lot more details. He was an eyewitness to the Temple’s destruction and lived in the decades leading up to it. Josephus records several major incidents that sparked the Great Revolt (in his Antiquities of the Jews, Book XX, Ch. 5; and Wars of the Jews, Book II, Ch. 12). One was when a Roman soldier mocked the Jews and made inappropriate gestures to worshippers at the Temple during Pesach. The Jews started to riot, leading to a Roman response that killed several thousand Jews, mainly due to a panicked stampede. (Josephus says as many as twenty thousand may have died.)

Then, a Roman official named Stephanus was attacked and robbed, probably by Zealots, near the town of Beit Haran. In response, the Romans plundered the town, and in the process one Roman soldier tore up a Torah scroll and burned it. The Jews were livid and riots erupted. The Roman governor at the time, Ventidius Cumanus, actually had to publicly execute his own Roman soldier in order to restore calm!

The final straw took place in the year 66. Josephus describes how a group of Jewish rebels slaughtered some Romans at Masada. At the same time, a prominent kohen named Elazar ben Chananiah decided to stop offering sacrifices in the Temple on behalf of Rome and the Caesar. (This may be connected to the famous story of “Kamtza and Bar Kamtza” as given in the Talmud, Gittin 55b. Interestingly, in his autobiography, Josephus does briefly mention a man named “Compsus, son of Compsus”, who was one of three great “men of worth and gravity” in the city of Tiberias. Some say this is the bar Kamtza of the Talmud!) Elazar ben Chananiah was the son of the kohen gadol, and Josephus describes him as a bold young man who had been appointed “governor of the Temple” (see Wars II, 17:2, 6).

The Romans responded to these events by sending troops under Cestius Gallus to teach the Jews a lesson. Surprisingly, Jewish rebels quickly routed Gallus’ forces. The following year, Nero sent the famed general Vespasian with a much larger contingent. It should have been a quick victory, but the Jewish rebels fought valiantly and kept the Romans at bay for several years. In July of 69, Vespasian was elected the new Caesar and left for Rome, leaving behind his son Titus to finish the job. Here the plot thickens: Vespasian knew that his son was inexperienced and couldn’t do it alone. So, he called up one of his top military geniuses from Egypt to serve as Titus’ chief of staff and second-in-command. This high-ranking general happened to be a Jew named Tiberius Julius Alexander.

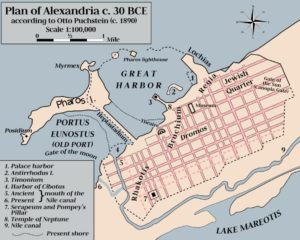

Nobles of Alexandria

In the first centuries of the Common Era, the world’s most populous Jewish city was Alexandria, Egypt. Hundreds of thousands of Jews lived there, making up as much as half the city’s population. Our Sages note how the Great Synagogue of Alexandria was so large it fit twice as many Jews as came out of Egypt during the Exodus! (See Tosefta, Sukkah 4:4) Alexandria even boasted its own “holy temple” of sorts, in nearby Leontopolis, where sacrifices were offered by kohanim, as described in the Talmud (Menachot 109a) and by Josephus (Antiquities, XIII, Ch. 3). (For more on the Leontopolis Temple, and how it came to an end, see ‘The Secret History of the Holy Temple’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.)

In the first centuries of the Common Era, the world’s most populous Jewish city was Alexandria, Egypt. Hundreds of thousands of Jews lived there, making up as much as half the city’s population. Our Sages note how the Great Synagogue of Alexandria was so large it fit twice as many Jews as came out of Egypt during the Exodus! (See Tosefta, Sukkah 4:4) Alexandria even boasted its own “holy temple” of sorts, in nearby Leontopolis, where sacrifices were offered by kohanim, as described in the Talmud (Menachot 109a) and by Josephus (Antiquities, XIII, Ch. 3). (For more on the Leontopolis Temple, and how it came to an end, see ‘The Secret History of the Holy Temple’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.)

One of the most illustrious families of kohanim in Alexandria produced the great Jewish philosopher Philo (c. 20 BCE-50 CE), who may have been history’s first official Torah commentator. Philo’s brother was Alexander, whom Josephus describes as the richest Jew in Alexandria. He was close with the Roman authorities, and eventually became the alabarch, the official head of Jewish affairs, and overseer of Alexandria harbour’s customs and duties. Josephus describes how, at one point, Alexander the Alabarch renovated the Second Temple in Jerusalem, and overlaid nine of its gates with silver and gold (Wars, V, 5:3). It is therefore especially ironic that his son would be the one leading the way to the Temple’s destruction.

A 1572 sketch of ancient Alexandria, highlighting the pharos, the city’s world-famous “Great Lighthouse”.

Alexander’s son Tiberius Julius appears to have married the daughter of King Agrippa I, the last Herodian king of Judea (whom our Sages actually described positively). Unfortunately, he turned his back on Judaism and wanted to be entirely Roman, for which both his uncle Philo and Josephus condemn him in their writings. Tiberius became close friends with Emperor Claudius, who appointed him as an official in one of the Egyptian provinces. After four years there, he was made governor of Judea. He ruled in Jerusalem with an iron fist, and executed several prominent Zealots.

Sadly, Jews executing other Jews was not a rare occurrence at that time. Indeed, our Sages state that the Second Temple was destroyed due to “bloodshed” (Shabbat 33a). It was not just low-level hatred and resentment, the sinat chinam was tragically at the level of murder. For instance, Josephus tells us how a Zealot leader named Menachem, son of Yehuda the Galilean, had the kohen gadol Chananiah assassinated together with his brother. In turn, Menachem was himself abducted from the Temple grounds, tortured and killed (Wars II, 17:9).

In another infamous case, our Sages state that the students of Beit Shammai killed some students of Beit Hillel (Yerushalmi, Shabbat 1:4). Many commentators have stated that it could not be that Torah scholars literally killed each other—it must be a figurative statement. Others maintain they really did rise up against one another, and this is why the Talmud describes that day as the worst in Jewish history since the Golden Calf (when “man killed his brother, his fellow, his kin”, Exodus 32:27). Things were so bad in Jerusalem at the time that our Sages state in the final several decades before the Temple’s destruction, the chut shani, the red string tied to the Yom Kippur sacrificial goat, would no longer turn white to indicate God’s forgiveness (Yoma 39b).

It is all the more important to remember this today, when we see what is going on at the Kotel, with certain people descending to pathetic levels of bigotry and vandalism. The Talmud Yerushalmi states that there were 24 different sects or groups of Jews, all bickering with one another, when God decreed the Temple’s destruction. We do not need a repeat of this today, and the only way to bring back the Temple is to do the very opposite: to increase unity, understanding, dialogue, and ahavat chinam, baseless love. Philosophical and religious differences aside, anyone who does not understand this is fulfilling the old maxim that “every generation in which the Temple is not rebuilt is like the generation in which the Temple was destroyed”.

Destroying the Temple

Tiberius Julius Alexander only had a brief stint as governor of Judea, and was soon replaced by Cumanus (mentioned above). Tiberius decided to instead go down the military route and joined the Roman forces on several campaigns. Rising through the ranks, he became a fierce warrior and able general, and in 66 CE was appointed by Emperor Nero as the new Prefect of Egypt. The Great Revolt began shortly after, and Alexandrian Jews wished to fight alongside their brothers in Jerusalem. Tiberius knew he had to quash the Alexandrian rebellion quickly, and sent 2000 Roman soldiers into the city. Josephus states that Tiberius had no mercy, and slaughtered 50,000 Alexandrian Jews, with “no pity for infants, no respect for the aged; old and young were slaughtered right and left.”

Incredibly, it was Tiberius who helped orchestrate Vespasian’s rise to the emperorship. The Roman Senate had elected Vitellius as the new Caesar, but Tiberius had his troops declare Vespasian as the new emperor instead, and suppressed any opposition. Word of this inspired other generals across the Empire to do the same. Soon, Vespasian left Jerusalem to get rid of the competition in Rome and formally claim the throne. He put his trusted (Jewish) general Tiberius Julius Alexander in his place, alongside his son Titus.

Tiberius turned up the heat in the Siege of Jerusalem. Within a year, the city was in desperation and ready to be attacked. The walls were breached, and the massacres began. When the command was given to destroy the Temple, it seems Tiberius’ Jewish sparked kicked in after all, and he issued a counter-command to spare the Temple and put out the flames. Nonetheless, the situation was so chaotic that it was hard to rein in the Roman soldiers. When a group of Jews entered the Holy of Holies seeking refuge, a Roman soldier lit the space on fire. The flames grew out of control, the soldiers were more interested in plunder and loot, and the Temple was destroyed.

Jewish rebels continued to fight a guerrilla war against Rome until 73, when the last Jewish stronghold at Masada was quelled. (Ironically, Josephus noted the war began when Jews attacked Romans at Masada!) Tiberius Julius Alexander went on to become Prefect of the Praetorian Guard in Rome, making him the highest-ranking Jew in Roman history. He would have probably lived out his life in Rome, alongside Josephus, who was at the same time writing his immensely-important works that give us an invaluable glimpse as to what really went on when the Temple was destroyed.

To access Josephus’ Antiquities online, see here, and for Wars of the Jews, here.

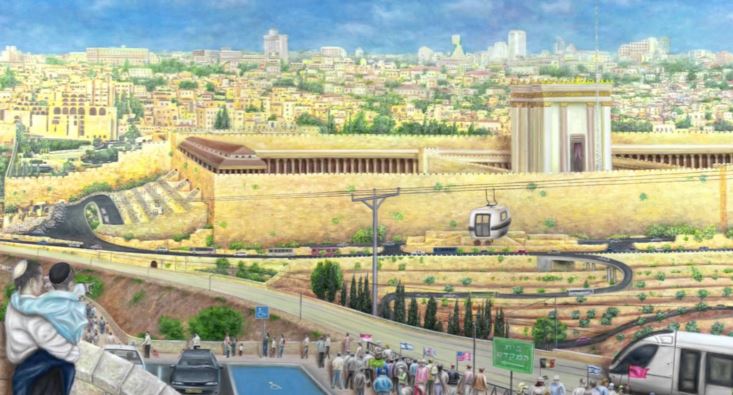

‘Going Up To The Third Temple’ by Ofer Yom Tov

Pingback: Why Was the Temple Really Destroyed? | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The 18 Decrees of Beit Shammai | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Things You Didn’t Know About the Arizal | Mayim Achronim