In this week’s parasha, Vayishlach, we read of Jacob’s famed battle with the angel. According to many sources, Jacob battled Esau’s guardian angel. While the identity of the angel is concealed in the plain text of the Torah, Jewish tradition associates this angel with Samael. That name is one of the most famous—or infamous—of all angelic entities, not just in Judaism, but also in Christianity, Gnosticism, and other Near Eastern traditions. Who is Samael?

‘Jacob Wrestling with an Angel’ by Charles Foster

The Primordial Serpent

One of the most ancient Jewish mystical works is Sefer HaBahir. At the very end of the text (ch. 200), we are told that Samael was the angel that came down to the Garden of Eden in the form of a serpent. We read here that one of his punishments was to become the guardian angel of the wicked Esau. The Bahir explains that Samael was jealous of man, and disagreed with the fact that God gave man dominion over the earth. He came down with the mission of corrupting mankind.

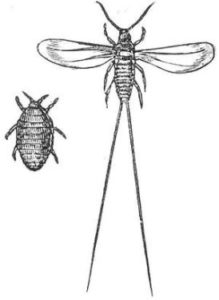

The Midrash (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 14) seems to agree, describing how God “cast down Samael and his troop from their holy place in Heaven.” In the previous chapter of the same Midrash, we read how Samael is unique in that, while other angels have six wings, Samael has twelve, and “commands a whole army of demons”. The Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572) adds that Samael is in charge of all the “male” demons, called Mazikim, while his “wife” Lilith is in charge of all the “female” demons, called Shedim (Sha’ar HaPesukim on Tehilim). He further associates Lilith with the sword of the “Angel of Death”.

A little-known apocryphal text called the Ascension [or Testament] of Moses (dating back at least to the early 1st century CE) states that Samael is the one “who takes the soul away from man”, directly identifying him with the Angel of Death. This ties neatly into his name, since Samael (סמאל) literally means “poison of God”. Indeed, the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 20b) states that the Angel of Death takes a person away by standing over them with his sword, before a drop of poison falls from the tip of the sword into the victim’s mouth. Elsewhere, the Talmud (Bava Batra 16a) tells us that the Angel of Death is the same entity as Satan, and as the source of the yetzer hara (the Evil Inclination).

In his Kabbalah (pg. 385), Gershom Scholem brings a number of sources that state Satan and Samael are one and the same, together with another figure called Beliar, or Belial. There are those who say that while Satan simply means “prosecutor”, and is only a title, Samael is actually his proper name. The Zohar (on parashat Shoftim) appears to agree, stating that the two main persecuting forces in Heaven are Samael and the Serpent. Some sources depict Samael as actually riding upon the Serpent!

Belial, meanwhile, is a term that appears many times in the Tanakh. It is first found in Deuteronomy 13:14, in a warning that certain bnei Belial will come out to tempt Israel into idolatry. While the simple meaning (and the way it is generally translated) is “base” or “wicked men”, the Kabbalistic take is that it refers to impure spirits that come to lure Israel to sin. Note that the Torah says these bnei Belial will emerge from among our own people.

Not surprisingly, the Zohar (Raya Mehemna on Ki Tetze) says that there are a very small group of “Jewish” imposters who actually worship Samael. These are the ones that give all Jews a bad name, and aim to reverse all the good that Jews do in the world. We have written much of this small group of imposters before, as they are more commonly referred to as the Erev Rav. The Zohar states that Samael and Lilith were once good angels before their “fall”, and began to be worshipped as deities in their own right in the pre-Flood generation. The people in those days worshipped them in order to manipulate them to do their bidding. The Erev Rav aims to do the same today. Thankfully, God will destroy them all in the End of Days, and this is the deeper meaning of Zechariah 13:2:

“And it shall come to pass in that day,” says the Lord of Hosts, “that I will cut off the names of the idols out of the land, and they shall no more be remembered; and also I will cause the prophets and the unclean spirit to pass out of the land.”

Which prophets is God referring to? Those leaders of the Erev Rav that attempt to convince the masses that they are “prophets”, only to lead the people astray.

With this in mind, Jacob’s battle with Samael takes on a whole new meaning. It reminds us that the job of each Jew is to fight Samael and all his evil minions—the bnei Belial, the Erev Rav—tooth and nail, unceasingly, all through the dark night, as Jacob did. We must always stand on the side of light and truth, holiness and Godliness. This makes us Israel, as Jacob was renamed, the ones who fight alongside God. The Jewish people are meant to be God’s holy warriors in this world.

Battling 365 Days of the Year

Commenting on this week’s parasha, the Zohar states that there are 365 angels ruling over each of the 365 days of the solar year. These further correspond to the 365 gidim (“sinews”, or more accurately, major nerves) of the human body, as Jewish tradition maintains. In Jacob’s battle, Samael struck him in the thigh, on his gid hanashe, the sciatic nerve. For this reason, the Torah tells us, the Jewish people do not eat the sciatic nerve “until this day” (Genesis 32:33). Removing this sinew is a key part of koshering meat. In most places, since removing it is so difficult, they simply do not include the back half of the cow or sheep in the kosher meat process.

The Zohar says that since there are 365 days corresponding to 365 sinews, the gid hanashe corresponds to a specific day of the year, too, of course. Which day is that? Tisha b’Av, the most tragic day in Jewish history. The Zohar concludes that Samael is the angel that rules over this day, which is why it is so “unlucky” and sad. At the same time, it suggests that Jacob fought Samael on that same day, so even when Samael is at his strongest, each Jew has the power to defeat him.

Interestingly, the Talmud has a different approach. There we read that Satan rules 364 days of the year! (Nedarim 32b) This is why the gematria of HaSatan (השטן, the way it appears in the Tanakh) is 364. According to the Talmud, the one day a year that Satan “rests” is Yom Kippur. Thus, Yom Kippur is a particularly favourable day to repent and to have God accept our prayers. The Midrash (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 46) takes it one step further and states that not only does Satan rest on Yom Kippur, but he actually crosses the floor in the Heavenly Court and joins the defense!

How do we reconcile the seeming contradiction between the Talmud and the Zohar? Perhaps Samael, before his “fall”, was originally appointed to rule over Tisha b’Av. After his rebellion, he sought to dominate as much of the year as possible, and remains at large 364 days of the calendar, being particularly strong on Tisha b’Av. Only on Yom Kippur does God make sure that Satan has no dominion at all.

This should remind us that, at the end of the day, God is infinite and omnipotent, and there is none that can stand before Him. Satan or Samael can be winked out of existence instantaneously if God so willed it. Alas, the impure spirits still have a role to play in history. They will soon meet their end:

Kabbalistic texts state that Satan will lead one last battle in the End of Days, against Mashiach. He will come as the dreaded Armilus. In Sefer Zerubavel, Armilus is identified with Satan himself in bodily form, while in Nistarot d’Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, he is the son of Satan. He will seek to kill Mashiach, and he may succeed in killing Mashiach ben Yosef, before being in turn extinguished by Mashiach ben David. This is why the Arizal instituted a custom to insert a short prayer for Mashiach ben Yosef, that he should survive, in the blessing for Jerusalem in the Amidah. We have written elsewhere, though, why Mashiach ben Yosef must die to accomplish an important tikkun (see ‘Secrets of the Akedah’ in Garments of Light).

Until then, how do we keep Samael away? The Arizal (Sha’ar HaMitzvot on Shemot) taught not to pronounce his name out loud, for this attracts him. In Jewish tradition, we instead say the letters ס״ם, “samekh-mem”. The Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) stated that eating too much red meat during the week gives power to Samael. It is generally best to leave red meat consumption for Shabbat and holidays if possible. It goes without saying that one should eat kosher meat to avoid the gid hanashe. Meanwhile, the Talmud (Shabbat 30b) famously recounts how David kept the Angel of Death at bay by constantly being immersed in Torah study. We should be focused on study of holy texts, prayer, repentance, doing mitzvot and good deeds. Finally, we must do everything we can to defeat our own inner evil inclinations, struggling as long as it takes, unrelenting, as Jacob did in his battle. In the same passage where the Talmud speaks of the death of Mashiach ben Yosef (Sukkah 52a), it tells us:

In the time to come, the Holy One, blessed be He, will bring the Evil Inclination and slay it in the presence of the righteous and the wicked. To the righteous it will have the appearance of a towering hill, and to the wicked it will have the appearance of a hair thread. Both the former and the latter will weep: the righteous will weep saying, “How were we able to overcome such a towering hill?!” The wicked also will weep saying, “How is it that we were unable to conquer this hair thread?!” And the Holy One, blessed be He, will also marvel together with them, as it is said, “Thus says the Lord of Hosts, ‘If it be marvellous in the eyes of the remnant of this people in those days, it shall also be marvellous in My eyes…’” [Zechariah 8:6]