Earlier this week we discussed the necessity of the Talmud, and of an oral tradition in general, to Judaism. We presented an overview of the Talmud, and a brief description of its thousands of pages. And we admitted that, yes, there are some questionable verses in the Talmud (very few when considering the vastness of it). Here, we want to go through some of these, particularly those that are most popular on anti-Semitic websites and publications.

An illustration of Rabbi Akiva from the Mantua Haggadah of 1568

By far the most common is that the Talmud is racist or advocates for the destruction of gentiles. This is based on several anecdotes comparing non-Jews to animals, or the dictum of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai that “the best of gentiles should be killed”. First of all, we have to be aware of the linguistic style of the Talmud, which often uses strong hyperbole that is not to be taken literally (more on this below). More importantly, we have to remember that these statements were made in a time where Jews were experiencing a tremendous amount of horrible persecution. Rabbi Shimon’s teacher, Rabbi Akiva was tortured to death by being flayed with iron combs. This is a man who never hurt anyone, who raised the status of women, sought to abolish servitude, preached that the most important law is “to love your fellow as yourself”, and taught that all men are made in God’s image (Avot 3:14). For no crime of his own, he was grotesquely slaughtered by the Romans. Rabbi Shimon himself had to hide from the Romans in a cave for 13 years with his son, subsisting off of nothing but carobs. The Jews in Sassanid Persia didn’t fare too much better. So, the anger and resentment of the Sages to their gentile oppressors sometimes come out in the pages of Talmud. Yet, the same Talmud insists “Before the throne of the Creator there is no difference between Jews and gentiles.” (TY Rosh Hashanah 57a). Moreover, a non-Jew who is righteous, and occupies himself with law and spirituality, is likened to a kohen gadol, the high priest (Bava Kamma 38a).

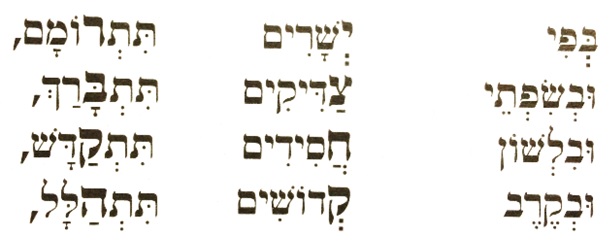

In fact, the contempt that the Sages sometimes had for gentiles is not simply because they were not Jewish, for we see that the Sages had the same contempt, if not more so, for certain other Jews! The Talmud (Pesachim 49b) warns never to marry an ‘am ha’aretz, an unlearned or non-religious Jew, and even compares such Jews to beasts. In the same way that gentiles are sometimes compared to animals, and in the same way Rabbi Shimon said they should “be killed”, Rabbi Shmuel said that the ‘am ha’aretz should be “torn like a fish”! Why such harsh words for other Jews? Because they, too, do not occupy themselves with moral development, with personal growth, or with the law. Therefore, they are more likely to be drawn to sin and immorality. After all, the very purpose of man in this world “is to perfect himself”, as Rabbi Akiva taught (Tanchuma on Tazria 5), and how can one do so without study? Still, the Sages conclude (Avot d’Rabbi Natan, ch. 16) that

A man should not say, “Love the pupils of the wise but hate the ‘am ha’aretẓ,” but one should love all, and hate only the heretics, the apostates, and informers, following David, who said: “Those that hate You, O Lord, I hate” [Psalms 139:21]

Rabbi Akiva is a particularly interesting case, because he was an ‘am ha’aretz himself in the first forty years of his life. Of this time, he says how much he used to hate the learned Jews, with all of their laws and apparent moral superiority, and that he wished to “maul the scholar like a donkey”. Rabbi Akiva’s students asked why he said “like a donkey” and not “like a dog”, to which Akiva replied that while a dog’s bite hurts, a donkey’s bite totally crushes the bones! We can learn a lot from Rabbi Akiva: it is easy to hate those you do not understand. Once Akiva entered the realm of the Law, he saw how beautiful and holy the religious world is. It is fitting that Rabbi Akiva, who had lived in both worlds, insisted so much on loving your fellow. And loving them means helping them find God and live a holy, righteous life, which is why Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani (the same one who said that the ‘am ha’aretz should be devoured like a fish) stated that:

He who teaches Torah to his neighbour’s son will be privileged to sit in the Heavenly Academy, for it is written, “If you will cause [Israel] to repent, then will I bring you again, and you shall stand before me…” [Jeremiah 15:19] And he who teaches Torah to the son of an ‘am ha’aretz, even if the Holy One, blessed be He, pronounces a decree against him, He annuls it for his sake, as it is written, “… and if you shall take forth the precious from the vile, you shall be as My mouth…” [Bava Metzia 85a]

Promiscuity in the Talmud

Another horrible accusation levelled against the rabbis of the Talmud is that they were (God forbid) promiscuous and allowed all sorts of sexual indecency. Anyone who makes such a claim clearly knows nothing of the Sages, who were exceedingly modest and chaste. They taught in multiple places how important it is to guard one’s eyes, even suggesting that looking at so much as a woman’s pinky finger is inappropriate (Berakhot 24a). Sexual intercourse should be done only at night or in the dark, and in complete privacy—so much so that some sages would even get rid of any flies in the room! (Niddah 17a) Most would avoid touching their private parts at all times, even while urinating (Niddah 13a). The following page goes so far as to suggest that one who only fantasizes and gives himself an erection should be excommunicated. The Sages cautioned against excessive intercourse, spoke vehemently against wasting seed, and taught that “there is a small organ in a man—if he starves it, it is satisfied; if he satisfies it, it remains starved.” (Sukkah 52b)

Anti-Semitic and Anti-Talmudic websites like to bring up the case of Elazar ben Durdya, of whom the Talmud states “there was not a prostitute in the world” that he did not sleep with (Avodah Zarah 17a). Taking things out of context, what these sites fail to bring up is that the Talmud, of course, does not at all condone Elazar’s actions. In fact, the passage ends with Elazar realizing his terribly sinful ways, and literally dying from shame.

Another disgusting accusation is that the Talmud permits pederasty (God forbid). In reality, what the passage in question (Sanhedrin 54b) is discussing is when the death penalty for pederasty should be applied, and at which age a child is aware of sexuality. Nowhere does it say that such a grotesque act is permitted. The Sages are debating a sensitive issue of when a death penalty should be used. Shmuel insists that any child over the age of three is capable of accurately “throwing guilt” upon another, and this would be valid grounds for a death penalty. Elsewhere, the Talmud states that not only do pederasts deserve to be stoned to death, but they “delay the coming of the Messiah” (Niddah 13b).

The Talmud is similarly accused of allowing a three year old girl to be married. This is also not the whole picture. A father is allowed to arrange a marriage for his daughter, but “it is forbidden for one to marry off his daughter when she is small, until she grows up and says ‘this is the one I want to marry.’” (Kiddushin 41a) Indeed, we don’t see a single case of any rabbi in the Talmud marrying a minor, or marrying off their underage daughter. Related discussions appear in a number of other pages of the Talmud. In one of these (Yevamot 60b), Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai states that a girl who was converted to Judaism before three years of age is permitted to marry a kohen, although kohanim are generally forbidden from marrying converts. This, too, has been twisted as if Rabbi Shimon allowed a kohen to marry a three-year old. He did not say this at all, rather stating that a girl under three who is converted to Judaism (presumably by her parents, considering her young age) is actually not considered a convert but likened to a Jew from birth. Once again we see the importance of proper context.

Science in the Talmud

Last week we already addressed that scientific and medical statements in the Talmud are not based on the Torah, and are simply a reflection of the contemporary knowledge of that time period. As we noted, just a few hundred years after the Talmud’s completion, Rav Sherira Gaon already stated that its medical advice should not be followed, nor should its (sometimes very strange) healing concoctions be made. The Rambam (Moreh Nevuchim III, 14) expanded this to include the sciences, particularly astronomy and mathematics, which had come a long way by the time of the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204). The Rambam did not state that the Sages are necessarily wrong on scientific matters—for indeed we see that they are often quite precise—nonetheless:

You must not expect that everything our Sages say respecting astronomical matters should agree with observation, for mathematics were not fully developed in those days: and their statements were not based on the authority of the Prophets, but on the knowledge which they either themselves possessed or derived from contemporary men of science.

Some scientific statements of the Talmud which have been proven wrong include: The earth’s crust is 1000 cubits thick (Sukkot 53b)—today we have mines that go down four kilometres, which is well over 5000 cubits at least! Lions, bears, and elephants have a gestation period of three years (Bekhorot 8a)—while the Talmud is right by previously stating that cows have a nine-month gestation period, lions actually have gestation of 110 days, bears of 95-220 days depending on the species, and elephants of 22 months.

On the other hand, the Talmud is accurate, for example, when describing the water cycle (Ta’anit 9a), with Rabbi Eliezer explaining that water evaporates from the seas, condenses into clouds, and rains back down. It is also surprisingly close when calculating the number of stars in the universe (Berakhot 32b), with God declaring:

… twelve constellations have I created in the firmament, and for each constellation I have created thirty hosts, and for each host I have created thirty legions, and for each legion I have created thirty cohorts, and for each cohort I have created thirty maniples, and for each maniple I have created thirty camps, and to each camp I have attached three hundred and sixty-five thousands of myriads of stars, corresponding to the days of the solar year, and all of them I have created for your sake.

Doing the math brings one to 1018 stars. This number was hard to fathom in Talmudic times, and even more recently, too (I personally own a book published in the 1930s which states that scientists estimate there are about a million stars in the universe), yet today scientists calculate similar numbers, with one estimate at 1019 stars.

History in the Talmud

When it comes to historical facts the Talmud, like most ancient books, is not always accurate. Historical knowledge was extremely limited in those days. There was no archaeology, no linguistics, and no historical studies departments; neither were there printing presses or books to easily preserve or disseminate information. This was a time of fragile and expensive scrolls, typically reserved for Holy Scriptures.

All in all, the Talmud doesn’t speak too much of history. Some of its reckonings of kings and dynasties are certainly off, and this was recognized even before modern scholarship. For example, Abarbanel (1437-1508) writes of the Talmud’s commentaries on the chronology in Daniel that “the commentators spoke falsely because they did not know the history of the monarchies” (Ma’ayanei HaYeshua 11:4).

The Talmud has also been criticised for exaggerating historical events. In one place (Gittin 57b), for instance, the Talmud suggests that as many as four hundred thousand myriads (or forty billion) Jews were killed by the Romans in Beitar. This is obviously impossible, and there is no doubt the rabbis knew that. It is possible they did not use the word “myriads” to literally refer to 10,000 (as is usually accepted) but simply to mean “a great many”, just as the word is commonly used in English. If so, then the Talmud may have simply meant 400,000 Jews, which is certainly reasonable considering that Beitar was the last stronghold and refuge of the Jews during the Bar Kochva Revolt.

Archaeological remains of the Beitar fortress.

Either way, as already demonstrated the Talmud is known to use highly exaggerated language as a figure of speech. It is not be taken literally. This is all the more true for the stories of Rabbah Bar Bar Chanah, which are ridiculed for their embellishment. Bar Bar Chanah’s own contemporaries knew it, too, with Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish even refusing to take his helping hand while nearly drowning in the Jordan River! (Yoma 9b) Nonetheless, the Talmud preserves his tall tales probably because they carry deeper metaphorical meanings.

Having said that, there are times when the Talmud is extremely precise in its historical facts. For example, it records (Avodah Zarah 9a) the historical eras leading up to the destruction of the Second Temple:

…Greece ruled for one hundred and eighty years during the existence of the Temple, the Hasmonean rule lasted one hundred and three years during Temple times, the House of Herod ruled one hundred and three years. Henceforth, one should go on counting the years as from the destruction of the Temple. Thus we see that [Roman rule over the Temple] was two hundred and six years…

We know from historical sources that Alexander conquered Israel around 331 BCE. The Maccabees threw off the yoke of the Greeks around 160 BCE, and Simon Maccabee officially began the Hasmonean dynasty in 142 BCE. That comes out to between 171 and 189 years of Greek rule, depending on where one draws the endpoint, right in line with the Talmud’s 180 years. The Hasmoneans went on to rule until 37 BCE, when Herod took over—that’s 105 years, compared to the Talmud’s 103 years. And the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, making Herodian rule over the Temple last about 107 years. We also know that Rome recognized the Hasmonean Jewish state around 139 BCE, taking a keen interest in the Holy Land thereafter, and continuing to be involved in its affairs until officially taking over in 63 BCE. They still permitted the Hasmoneans and Herodians to “rule” in their place until 92 CE. Altogether, the Romans loomed over Jerusalem’s Temple for about 209 years; the Talmud states 206 years. Considering that historians themselves are not completely sure of the exact years, the Talmud’s count is incredibly precise.

Understanding the Talmud

Lastly, it is important never to forget that the Talmud is not the code of Jewish law, and that Judaism is far, far more than just the Talmud. There are literally thousands of other holy texts. Jews do not just study Talmud, and even centuries ago, a Jew who focused solely on Talmud was sometimes disparagingly called a hamor d’matnitin, “Mishnaic donkey”. The Talmud itself states (Kiddushin 30a) that one should spend a third of their time studying Tanakh, a third studying Mishnah (and Jewish law), and a third studying Gemara (and additional commentary). The Arizal prescribes a study routine that begins with the weekly parasha from the Five Books of Moses, then progresses to the Nevi’im (Prophets) and Ketuvim, then to Talmud, and finally to Kabbalah (see Sha’ar HaMitzvot on Va’etchanan). He also states emphatically that one who does not study all aspects of Judaism has not properly fulfilled the mitzvah of Torah study.

A Torah scroll in its Sephardic-style protective case, with crown.

Those who claim that Jews have replaced the Tanakh with the Talmud are entirely mistaken: When Jews gather in the synagogue, we do not take out the Talmud from the Holy Ark, but a scroll of Torah. It is this Torah which is so carefully transcribed by hand, which is adorned with a crown to signify its unceasing authority, and before which every Jew rises. After the Torah reading, we further read the Haftarah, a selection from the Prophets. At no point is there a public reading of Talmud. As explained previously, the Talmud is there to help us understand the Tanakh, and bring it to life.

Ultimately, one has to remember that the Talmud is a continuing part of the evolution of Judaism. We wrote before how we were never meant to blindly follow the Torah literally, but rather to study it, develop it, grow together with it, and extract its deeper truths. The same is true of the Talmud—the “Oral” Torah—and of all others subjects within Judaism, including Midrash, Kabbalah, and Halacha. Judaism is constantly evolving and improving, and that’s the whole point.

For more debunking of lies and myths about the Talmud, click here.