With gratitude to my dear friend Rabbi Yehoshua Gerzi, who first suggested the idea.

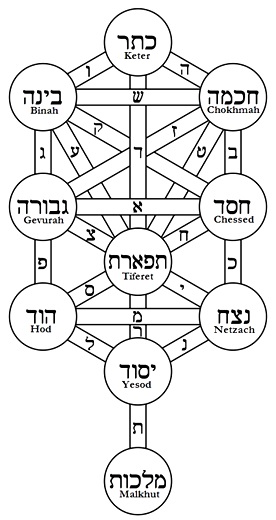

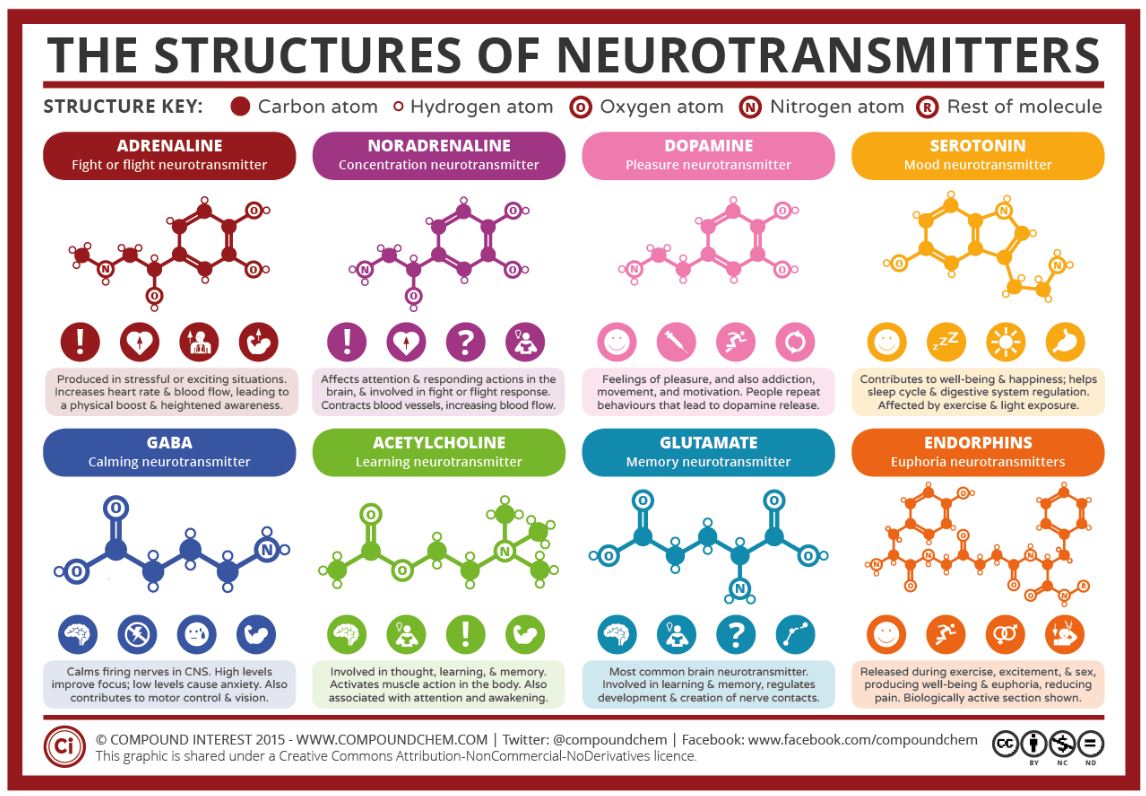

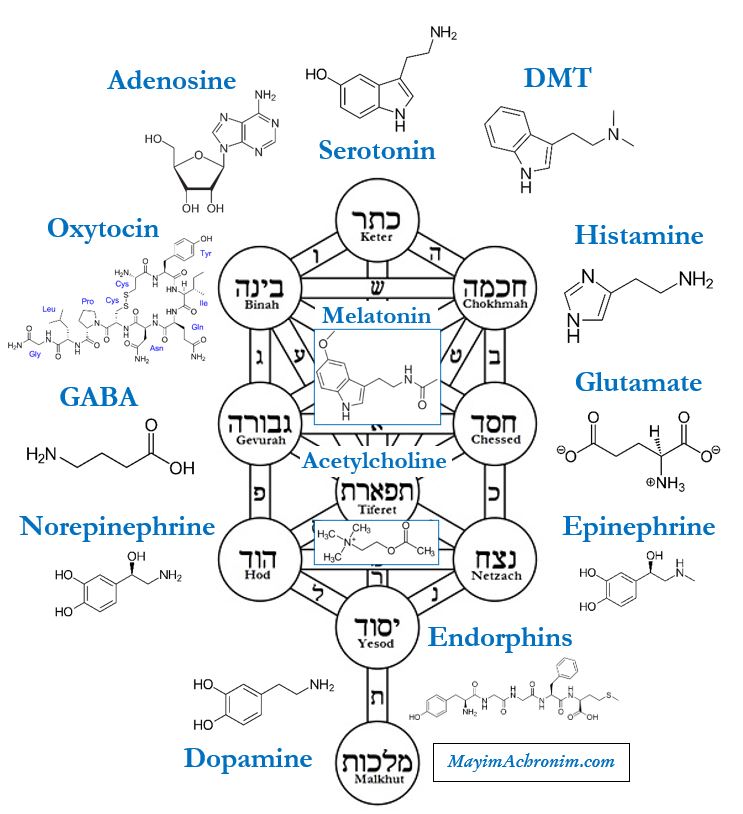

The centrepiece of this week’s parasha, Yitro, is the Ten Commandments relayed at Mount Sinai. As is well-known, all “tens” in the Torah are connected and parallel each other, starting with the Ten Utterances of Creation and the Ten Sefirot, the ten trials of Abraham, the Ten Plagues, and the Ten Commandments. Similarly, there are patterns of ten all over science and nature. Our entire mathematical system is built upon a base-10 system of digits. The human body has ten senses. Relatedly, we find that the human brain relies primarily on a set of ten neurotransmitters (out of a total of about forty altogether). This is particularly relevant to this week’s parasha, where the Sinai Revelation is described as something akin to a synesthetic and psychedelic experience. What are the brain’s major neurotransmitters, and what is their spiritual root in the Sefirot?

The most abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, by far, is glutamate. Glutamate is a small molecule closely related to the the amino acid glutamic acid, and made from the similar amino acid glutamine. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter whose job is to turn things “on”. It is vital for learning, memory, and the formation of new synapses between brain cells. It is also used to make a different neurotransmitter which has the exact opposite role, to turn things “off”: GABA. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. It is also important for brain development, and is involved in regulating moods, and blood sugar, too (directly affecting insulin-producing cells in the pancreas). Alcohol’s effect on the brain is caused by increasing levels of GABA, resulting in an inhibitory effect.

In terms of Sefirot, it is quite clear that glutamate and GABA parallel Chessed and Gevurah, “positive” and “negative” energies that balance each other out and are both vital for healthy functioning. Recall that Chessed is often referred to as Gedulah, “largeness”, fitting for glutamate which is the most abundant neurotransmitter in the body. Meanwhile, mystical texts parallel red wine (and, by extension, all alcohol) to the realm of Gevurah, further solidying the connection to GABA.

It is worth noting that glutamate activates the tongue’s “savoury” (or umami) taste receptors. This is why monosodium glutamate, infamously known as MSG, is added to many foods and snacks. Some have argued that since glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter, too much MSG consumption can result in “excitotoxicity” in the brain, possibly damaging brain cells or interfering with brain development. This is why people often look for MSG on labels to avoid them, so food producers use alternate names to avoid detection, including “flavour enhancer 621” or even just “yeast extract” or “autolyzed yeast”.

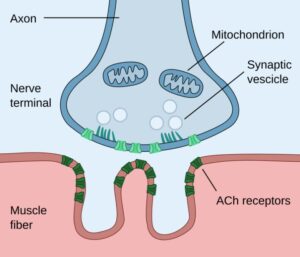

At the neuromuscular junction, the axon (top) releases acetylcholine, which then binds acetylcholine (ACh) receptors on the muscle, ultimately triggering a contraction.

The next major neurotransmitter is acetylcholine. It is involved in excitation, learning, and memory, as well, but has many more roles all over the body. Perhaps most importantly, acetylcholine is the chemical that transforms the brain’s electrical signals into muscle contractions. At every neuromuscular junction between nerves and skeletal muscles is acetylcholine. It is vital for the heart, too, and regulates heart rate and blood pressure. Acetylcholine is precisely the central Sefirah of Tiferet, the only one that intertwines with all other Sefirot, sending energy in all directions, and serving as the “heart” of the Sefirot.

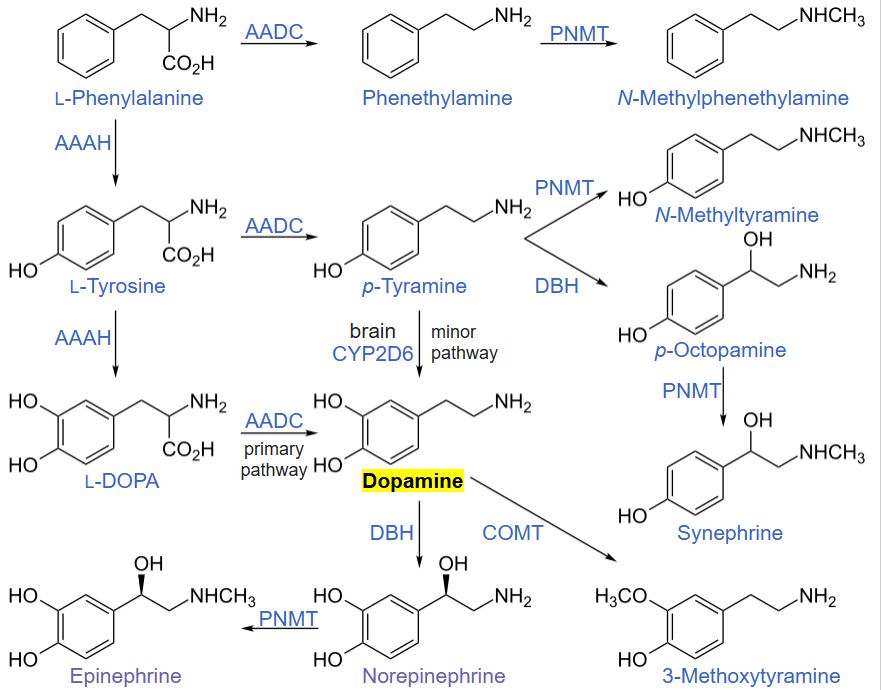

The next two Sefirot, Netzach and Hod, always come in a pair, their literal names meaning “victory” and “glory”. They are compared to the “legs”, and are sources of strength, elevation, and prophecy. Of course, they neatly parallel the twin pair of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine, the main neurotransmitters in the body’s sympathetic “fight-or-flight” response. These neurotransmitters turn up one’s heart rate, breath rate, stress levels, alertness, attention, and focus. No victory or glory was ever achieved in battle (or at a sports game) without a steady flow of adrenaline in the participants. Medically, epinephrine is most commonly used to stop allergic reactions, asthma attacks, and heart attacks, making it a key life-saver (another point for Netzach). Meanwhile, many medications for ADHD and depression upregulate the body’s norepinephrine levels.

We then get to Yesod, the domain of pleasure and intimacy. This corresponds to endorphins, the body’s natural painkillers and pleasure-producers. Release of endorphins from the pituitary gland is the primary cause of sexual pleasure. (The pituitary gland also releases hormones that control the reproductive system and production of both male and female gametes.) The term “endorphin” comes from endogenous morphine, and many drugs and painkillers are actually endorphin mimics. In fact, these are some of the most addictive drugs—including opioids, which are tragically resulting in the deaths of countless people. It is fairly well-known that Kabbalistic texts pinpoint life’s most difficult test to be in the realm of Yesod, and the final tikkun of the pre-Mashiach generation is specifically about rectifying Yesod—which certainly explains the world we see around us today, on many levels.

Finally, we come to Malkhut at the base of the Sefirot, where the final reward lies after the test of Yesod is passed. This is the place of the reward hormone dopamine. Like other neurotransmitters, dopamine plays an important role in learning, memory, and concentration. However, its most famous role is to produce a sense of reward and positivity. Most recreational drugs (including nicotine, cannabis, cocaine, meth, and heroine) mimic dopamine or increase the amount of dopamine in the brain. It is interesting that in mystical texts Malkhut is always described as being “empty”, often devoid of its own energy, and is also called shiflut, “lowliness”. This might explain why people who are in such a state of lowliness or emptiness tend to abuse dopamine-type drugs.

The amino acid phenylalanine (top left) is used to produce a number of important neurotransmitters including dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine.

Now we come to the upper three Sefirot, the Mochin, most closely associated with the brain itself. The motherly Binah, also called Ima, neatly corresponds to the neurotransmitter and hormone oxytocin. Recall that it is oxytocin that causes contractions during childbirth, and is involved with production of breastmilk afterwards. Oxytocin plays a huge role (in men and women) in love and emotional attachment, trust and social bonding, sexual arousal, and even anger management.

On the other side is Chokhmah, the fatherly Abba. This corresponds well with a molecule that until recently was thought to be only a hormone, but is now recognized as an important neurotransmitter, too: histamine. Histamine is made directly from the amino acid histidine, and is popularly known for its role in the immune system and allergic responses. It was once thought that histamine is only made in the immune system and by immune cells. We now know it is produced by the brain as well, and is primarily involved with alertness (hence antihistamines causing drowsiness). More recently, it was found to play a key role in male arousal and erectile function. It also plays a protective role for neurons, and may be involved in forgetting unnecessary things (another stereotypical male trait).

At last, we get to the highest Sefirah of Keter, the root of willpower, ratzon. This is undoubtedly the all-important serotonin, deeply involved in our own human willpower. Serotonin is made from the amino acid tryptophan, and has countless functions in the brain and body. It plays key roles in the digestive system and circulatory system, serves as a growth factor for some cells and organs, and regulates bone mass. (Note that Keter is often referred to as the “skull”.) Its best-known role is in mood regulation, and a lack of serotonin (or rapid reuptake of it) causes depression and a lack of willpower. Many antidepressants target serotonin and serotonin-related receptors and channels, as do many antipsychotics and antimigraine drugs. Interestingly, psychedelic drugs like DMT, psilocybin, LSD, and peyote (mescaline) are also serotonin mimics. And this brings us to the hidden Sefirah of Da’at:

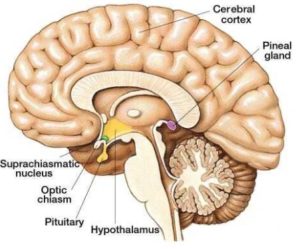

Da’at is thought of as the inner “realization” of Keter, the application of the initial will. It lies directly beneath Keter, between Chokhmah and Binah, usually concealed on a diagram of the Sefirot. It is sometimes described as the “integration” of knowledge. Da’at is intricately tied to Keter, so we should expect it to have its own related set of neurotransmitters. First is melatonin, the sleep hormone. Like serotonin (which also plays a small role in sleep), melatonin is made from tryptophan and has a very similar structure. Sleep is absolutely vital, shutting down our consciousness to allow the brain to reorganize and clean itself up. Like Da’at, sleep allows for “integration” of knowledge. Spiritually, our holy texts teach that most of the soul ascends to higher worlds during sleep, hence the body’s “dead-like” state. And this is what allows some of our dreams to be prophetic, as the wandering soul may pick up and retain higher knowledge from Above.

Scientifically, dreaming is very poorly understood and is still mostly a mystery. No one knows the biological reason for dreaming, but we do know it is essential, and going without dreaming (and the corresponding REM sleep) could be fatal. Incredibly, the Talmud (Berakhot 55a) knew this long ago, pointing out that the Hebrew word for “dream”, chalom, shares a root with “health” and “healing”, hachlamah. Based on Isaiah 38:16, the Talmud points out that dreaming keeps a person alive!

On the neurotransmitter level, dreaming has been linked to another tryptophan-derived molecule closely related to melatonin, popularly called DMT (dimethyltryptamine). DMT is famous for its hallucinogenic and psychedelic properties, and as the active ingredient in Ayahuasca. It can be highly transformative and therapeutic for many people. DMT is found in various plants (including those mentioned in the Torah, as described in a previous essay here.) And it is believed that tiny amounts of DMT may even be naturally produced by our brains, in the same pineal gland that makes melatonin. It may be involved in our own dreams, possibly including prophetic ones.

On the neurotransmitter level, dreaming has been linked to another tryptophan-derived molecule closely related to melatonin, popularly called DMT (dimethyltryptamine). DMT is famous for its hallucinogenic and psychedelic properties, and as the active ingredient in Ayahuasca. It can be highly transformative and therapeutic for many people. DMT is found in various plants (including those mentioned in the Torah, as described in a previous essay here.) And it is believed that tiny amounts of DMT may even be naturally produced by our brains, in the same pineal gland that makes melatonin. It may be involved in our own dreams, possibly including prophetic ones.

The pineal gland—often called the “third eye”—sits at the base of the brain, just as Da’at sits at the base of the Mochin, the literal “brain” of the Sefirot. The pineal gland actually contains photoreceptors like our eyes do, and in birds, for example, it sits at the top of the brain and picks up light signals to help birds navigate as they fly. This “third eye” pineal gland has been linked to the head tefillin worn between the eyes (as well as wearing a kippah, as explored in the past here). Amazingly, the Zohar taught centuries ago that the reason the head tefillin is split into four compartments (while the arm tefillin has just one) is both because it corresponds to the four light receptors in the eyes (the Zohar seems to have incredibly known about rods and cones!) as well as the four aspects of the Mochin! (Ie. Keter, Chokhmah, Binah, and Da’at. See Zohar III, 292b-293b, Idra Zuta.)

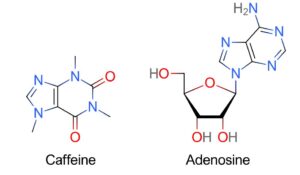

To complete the discussion, there is one more minor neurotransmitter that needs to be mentioned in the concealed “Da’at” category: adenosine. Adenosine is better known for its role as one of the four letters that make up our genetic alphabet (the adenine “A” of ACTG). But it happens to play a critical role in sleep and wakefulness, too. In fact, caffeine is an adenosine mimic, and specifically blocks adenosine receptors to prevent sleepiness! Lastly, while we can group adenosine, melatonin, and DMT together in the “Da’at” category, there is an alternative: In deeper mystical texts, two additional aspects of Keter are mentioned: Ta’anug, “pleasure”, and Emunah, “faith”. So, one might also align sleepy adenosine with Ta’anug (sleep being particularly associated with “pleasure” and oneg Shabbat), and spiritually uplifting DMT with Emunah.

To complete the discussion, there is one more minor neurotransmitter that needs to be mentioned in the concealed “Da’at” category: adenosine. Adenosine is better known for its role as one of the four letters that make up our genetic alphabet (the adenine “A” of ACTG). But it happens to play a critical role in sleep and wakefulness, too. In fact, caffeine is an adenosine mimic, and specifically blocks adenosine receptors to prevent sleepiness! Lastly, while we can group adenosine, melatonin, and DMT together in the “Da’at” category, there is an alternative: In deeper mystical texts, two additional aspects of Keter are mentioned: Ta’anug, “pleasure”, and Emunah, “faith”. So, one might also align sleepy adenosine with Ta’anug (sleep being particularly associated with “pleasure” and oneg Shabbat), and spiritually uplifting DMT with Emunah.

To summarize:

This weekend we welcome the month of Cheshvan and celebrate the first Rosh Chodesh of the new year 5785. In ancient times, the Sanhedrin would officially announce the start of a new month upon sighting of the new moon. Once the Sanhedrin was disbanded, the Sages fixed a set calendar for the millennia ahead. And since then, instead of a formal announcement of a new month upon new moon sighting, we recite a birkat levanah, a “blessing on the moon”. Where exactly did this blessing and practice originate? And what is the meaning behind its enigmatic text?

This weekend we welcome the month of Cheshvan and celebrate the first Rosh Chodesh of the new year 5785. In ancient times, the Sanhedrin would officially announce the start of a new month upon sighting of the new moon. Once the Sanhedrin was disbanded, the Sages fixed a set calendar for the millennia ahead. And since then, instead of a formal announcement of a new month upon new moon sighting, we recite a birkat levanah, a “blessing on the moon”. Where exactly did this blessing and practice originate? And what is the meaning behind its enigmatic text?