On Monday evening, people across the Western world will be celebrating Halloween. Today, it has become common in some places for Jews to partake in these festivities along with their non-Jewish neighbours. Might this be permissible? What are the origins of Halloween and should Jews participate in the holiday?

At first glance, the origins of Halloween appear to be Christian. The Christian “All Saints’ Day”, or “All Hallows’ Day” (hallow meaning “holy”) is commemorated on November 1st. In olden days it was customary for Christians to stay up the night before a holiday and hold a vigil, and the same was done for All Saints’ Day, hence All Saints’ Eve or All Hallows’ Eve, a name that eventually condensed into Hallowe’en, or simply Halloween. On this night, Christians would pray for the souls of the dead, and ring church bells for those in purgatory, as well as to remind the living about their ultimate fate. Some developed a custom to hand out “soul cakes” to commemorate the dead. It is believed that trick-or-treating came out of children and poor people going door-to-door to get soul cakes in exchange for prayers for the dead.

An antique Irish jack-o-lantern made from a carved out turnip.

However, as with many things Christian, the actual origins of Halloween date back to pagan practices. Like Christmas and Easter—which were instituted in place of earlier pagan festivals marking the winter solstice and spring fertility rituals—Halloween came in place of the earlier Celtic and Gaelic pagan holiday of Samhain. Samhain was celebrated on October 31st to mark the end of the harvest season and the start of the cold, dark, lifeless winter. It was believed that ghosts, fairies, and evil spirits emerged and would be more active through the difficult winter. Jack-o-lanterns were made (from pumpkins, turnips, and others) to ward off these evil spirits, and dressing up in ghastly costumes was thought to scare them away, too.

Meanwhile, people would leave offerings for the wicked spirits to appease them, as well as food and drink for the souls of their own deceased ancestors who were thought to return to Earth one night a year. This is the true origin of trick-or-treating! In some places, it was thought that the dead actually arose from their graves in the cemeteries to have a party, so a “danse macabre” re-enactment was performed, with people dressing up like the dead and going to dance and feast.

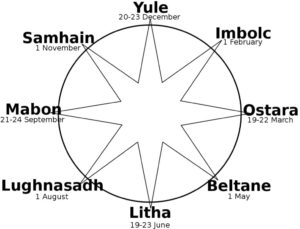

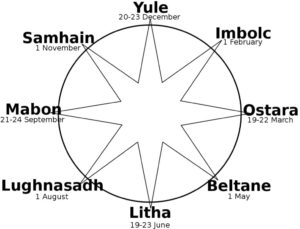

The Witch’s “Wheel of the Year”

Not surprisingly, Halloween was always an especially important day on the calendar for those practicing witchcraft and sorcery. Today, “neopagans” and Wiccans still consider Halloween one of their four major festivals (what they call a “Greater Sabbat”, unfortunately misappropriating our holy Shabbat). In short, Halloween is entirely a holiday of the Sitra Achra, a term for the realm of impurity and evil in Jewish mysticism.

With all of this in mind, there is no doubt at all that Jews should not participate in Halloween festivities. The Torah warns very strictly not to engage in any form of idolatry whatsoever, and something like 46 of the 613 commandments deal with various prohibitions related to idolatry and pagan practices. Jewish law forbids even dabbling in darkei Emori, referring to various other practices of pagans, even if they are not directly idolatrous (as the Torah states in Leviticus 18:3: “Do not walk in their ways…”) In fact, even Protestant Christians used to oppose Halloween, and the Puritans much more vehemently. Halloween was actually not celebrated at all in the Americas at first. It was only with the infux of Irish and Scottish immigrants to America in the 1800s that the holiday started to become popular.

Some will argue that Halloween no longer has any religious connotations, and is simply a secular holiday and a fun time for the kids. This is false for several reasons. First, Halloween is quite clearly all about highlighting the dead, evil spirits, ghosts, demons, and the like, which is fundamentally a religious notion. Second, regardless of how they may be viewed today, the practices of Halloween are deeply rooted in pagan rituals, and there are those who do indeed still celebrate Halloween as a genuine pagan religious festival.

More significantly, Halloween teaches children nothing positive. Young minds are instructed to go out and request candy from strangers (while every other day of the year being cautioned not to take candy from strangers!) Some learn that it is okay to commit mischief. Aside from that, Halloween decorations tend to be disturbing and frightening, and stimulate no beneficial or constructive emotions in anyone. (Worse still, wicked people have used Halloween as an opportunity to abduct children, to poison treats, even to stick pins and needles into candies, among all the other horrible things that have been done on Halloween over the years.)

In stark contrast to Halloween, Judaism has Purim, a festival of “light, happiness, joy, and honour” (Esther 8:16). A holiday to celebrate life and people uniting for a good cause. Instead of begging for candy, children are taught to go out and deliver mishloach manot treats to others. Instead of hooliganism, children are taught to give matnot l’evyonim, charity to the poor. Instead of dressing up as evil spirits, demons, and grotesque beings, children dress up as regal heroes, prophets, prophetesses, and holy patriarchs and matriarchs—and if not these then at least a dignified, modest costume. If you like Halloween, simply switch to Purim!

To conclude, there is little of value in Halloween, a holiday all about death and mischief, eating junk food, frightening other people, and glorifying horror and violence. The decorations are disturbing, the blood sugar levels troubling, and the message entirely ungodly. The spiritual risk in engaging in something so deeply pagan—when God warns so sternly to avoid anything even remotely hinting of paganism or idolatry—is far too great. Thus, not only should Jews not celebrate Halloween in any way, they should encourage each of their friends and neighbours to abolish this unhealthy and unholy satanic death ritual once and for all.

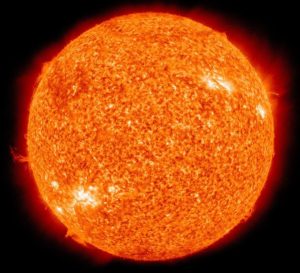

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.