This week’s parasha (in the diaspora) is Nasso, the longest in the Torah. In it, we read how God commanded Moses to instruct Aaron and his priestly descendants to bless the people with the following formula:

יְבָרֶכְךָ יְהוָה, וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ. יָאֵר יְהוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וִיחֻנֶּךָּ. יִשָּׂא יְהוָה פָּנָיו אֵלֶיךָ, וְיָשֵׂם לְךָ שָׁלוֹם

Loosely translated: “God bless you and protect you; God shine His Face upon you, and be gracious to you; God lift His Face upon you, and place peace upon you.” (Numbers 6:25-27) This unique, enigmatic phrase carries tremendous meaning, and an interesting history, too. In fact, the oldest Hebrew inscription of a Torah verse ever found is this blessing!

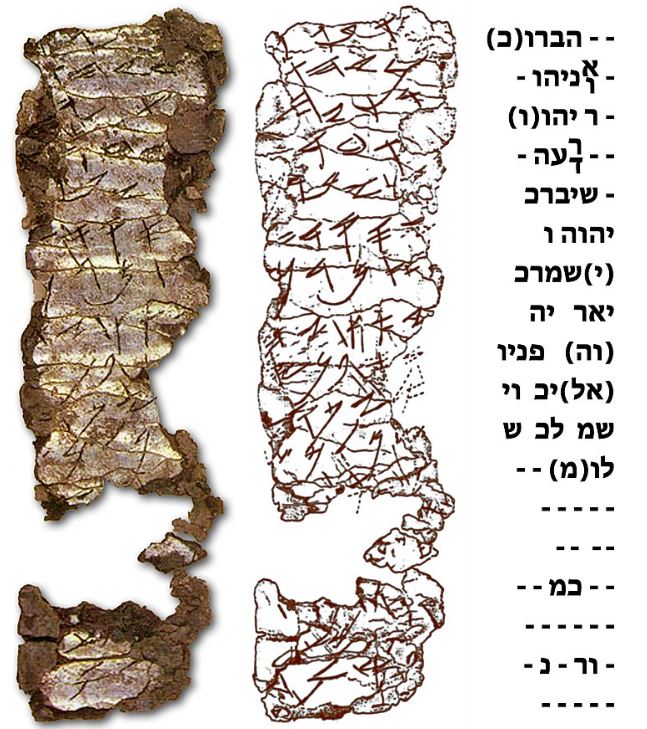

In 1979, archaeologists in Ketef Hinnom near the Old City of Jerusalem discovered two small silver scrolls. After painstakingly unravelling the fragile scrolls (a feat that took three years), they discovered that they were inscribed with Birkat Kohanim, the priestly blessing, along with a few introductory lines. The scrolls have been dated back to the 7th century BCE, and are considered among the greatest finds in the history of Biblical archaeology.

What secrets are buried within the words of Birkat Kohanim?

Silver scroll with priestly blessing, discovered near Jerusalem in 1979

Restoring Divine Light

In introducing the Priestly Blessing, the Torah commands koh tevarkhu, (כֹּ֥ה תְבָרְכ֖וּ), “thus shall you bless…” The Zohar (III, 146a) reminds us that koh is an allusion to the divine light of Creation. The value of koh (כה) is 25, hinting to the 25th word of the Torah, “light”. When Adam and Eve consumed the Fruit, that original divine light of Creation was concealed. This is the secret behind God calling to Adam: ayekah (איכה), usually translated simply as “where are you?” but really meaning ayeh koh, “where is the divine light?” Indeed, the very purpose of the kohen is to help restore some of that hidden divine light. This is why he is called a kohen!

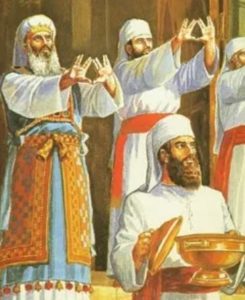

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.

In his commentary on the Torah, the Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1340) states that koh reminds us also of the Akedah, when Abraham told his attendants that he and Isaac would go ‘ad koh, “until there”. The deeper meaning is that Abraham saw the divine light emanating from the top of Mt. Moriah, the future site of the Holy of Holies. This is how he knew exactly where to bind Isaac. Previously, God had already blessed Abraham with the words כה יהיה זרעך, that his offspring would be luminous (and numerous) like the stars (Genesis 15:5). The Ba’al haTurim adds that the Shema has 25 letters for the same reasons and, amazingly, the term “blessing” is mentioned 25 times in the Torah, as is the word “peace”!

The first line of Birkat Kohanim has three words and fifteen letters, the Ba’al haTurim points out, alluding to the three Patriarchs—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—whose lives overlapped for 15 years. Recall that Abraham had Isaac when he was 100 years old, and Isaac had Jacob at 60 years old, ie. when Abraham was 160. Since we know Abraham passed away at the age of 175, there were 15 years when all three Avot lived together.

More specifically, the first line of the blessing is for Abraham, the second is for Isaac, and the third is for Jacob. This is why the second line speaks of illumination since, as is well-known, Isaac saw the intensely bright divine light unfiltered at the Akedah, and this is the reason he later became (physically) blind. The Sforno (Rabbi Ovadia ben Yakov Sforno, 1475-1550) adds that within the second line of the blessing is a request for God to give light to our eyes so that we could see God within all things, in all the wonders of the world, and in all the wealth (material and otherwise) that God has blessed us with.

The Ba’al haTurim continues that the third line of Birkat Kohanim is for Jacob, which is why it begins with the word yisa (יִשָּׂ֨א), reminding us of Genesis 29:1 when Jacob fled (וישא יעקב רגליו). It has seven words to indicate the subsequent births of the Twelve Tribes, who were (except for Benjamin) born to Jacob over a span of 7 years. The last line again has 25 letters to remind us of koh, and further alludes to the Sinai Revelation—another burst of divine light—when God said (Exodus 19:3) “thus [koh] you shall speak to the House of Jacob” (כה תאמר לבית יעקב). The Ba’al haTurim concludes that the final word of the blessing, shalom, has the same numerical value as Esau (376) to teach us that one should spread peace among all people, gentiles included, and even Esau!

Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 1089-1167) says that “peace” means complete peace, with not even a little stone or a wild animal to bother a person. Meanwhile, the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) says that “peace” here refers to shalom malkhut beit David, peace upon the kingdom of David and his dynasty. We may infer from this that it refers as well to geopolitical peace in Israel, and a request to hasten the coming of Mashiach. This is related to the Sforno’s interpretation, as he says the verse refers specifically to the World to Come in which, as described in the Talmud (Berakhot 17a), the righteous will bask peacefully in God’s glory.

May we merit to see it soon!

Finally, we have the citrus etrog. As expected, it has a very high vitamin C content, typically considered the most important vitamin in the body. The greatest champion of vitamin C was Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling. (Pauling is actually one of just four people to win two Nobel Prizes!) He was also ranked the 16th greatest scientist of all time. It was Pauling who first proposed that vitamin C can combat cold and flu infections. He later took it further and suggested vitamin C as a cure for all kinds of ailments, including cancer. His main work was in using vitamin C to treat heart disease and angina. Today, this method is still referred to as Pauling Therapy, though it remains controversial. Nonetheless, it is quite fitting since, of course, our Sages stated that the etrog parallels the heart!

Finally, we have the citrus etrog. As expected, it has a very high vitamin C content, typically considered the most important vitamin in the body. The greatest champion of vitamin C was Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling. (Pauling is actually one of just four people to win two Nobel Prizes!) He was also ranked the 16th greatest scientist of all time. It was Pauling who first proposed that vitamin C can combat cold and flu infections. He later took it further and suggested vitamin C as a cure for all kinds of ailments, including cancer. His main work was in using vitamin C to treat heart disease and angina. Today, this method is still referred to as Pauling Therapy, though it remains controversial. Nonetheless, it is quite fitting since, of course, our Sages stated that the etrog parallels the heart!