In this week’s parasha, Vayeshev, we read about the unfortunate sale of Joseph. Two big questions come up: First, why did Jacob deserve the cruel experience of not only losing his beloved son, but then also being tricked by his other sons? Second, why did Joseph deserve to be sold into slavery and spend a dozen years in prison? We know that God always acts justly, middah k’neged middah, “measure for measure”, so why did these two righteous figures deserve such tribulations?

The Zohar (I, 185b) on this week’s parasha points out some incredible parallels between what Jacob’s sons did to him, and what Jacob did to his father Isaac. Jacob had slaughtered some goats, was dressed up in “goat skins”, and presented his father with delicious goat meat in order to trick his father into a blessing. Jacob’s sons did the same in slaughtering a goat and dipping Joseph’s tunic in its blood to trick their father. Isaac had asked Jacob “Are you my son Esau, or not?” (ha’atah ze bni Esav im lo?) and Jacob’s sons similarly told him “Do you recognize this tunic to be your son’s, or not?” (haker na haktonet binkha im lo?) The result was that Isaac experienced a “great terror” (charadah gedolah), just as Jacob did. Thus, the Zohar says, what Jacob’s sons put him through is precisely what he had put his own father through! And this all came from God, who is medakdek when it comes to tzadikim: He is perfectly, mathematically, precise in His justice, measure for measure.

We can take this teaching in the Zohar one step further. We find that after Jacob tricked Esau, the latter was so angry he resolved to kill Jacob, which prompted Rebecca to send Jacob to her uncle in Haran. Although there are different opinions as to how long it took him to get to Haran, the pshat of the Torah is that he went to Haran immediately and spent twenty years with Lavan (Genesis 31:38). After he came back to the Holy Land, he reunited with his father Isaac whom he hadn’t seen for at least twenty years (Genesis 35:27). In the case of Joseph, the Torah tells us he was seventeen when he was sold (Genesis 37:2), and thirty when he became viceroy of Egypt (Genesis 41:46). There was then a seven-year period of plenty—until Joseph turned 37 years old—followed by the start of the famine, during which time Jacob was reunited with Joseph. Doing the math, we find that Jacob and Joseph were also separated for just over twenty years. Again, God’s retribution is exact!

Let’s turn to Joseph: why did he have to be sold into servitude and spend twelve years in an Egyptian prison? We read that he was an excellent servant in the house of Potiphar, and was put in charge of all of Potiphar’s affairs (Genesis 39:3). He lived very well there, until Potiphar’s wife tried to seduce him incessantly. When he kept refusing, she put in a false report of sexual assault, leading to Joseph’s arrest and imprisonment. This is not a coincidence either, for the parasha begins by telling us that Joseph would bring “bad reports” about his brothers to his father (Genesis 37:2). Just as Joseph made false reports about his siblings, Potiphar’s wife made a false report about Joseph! The result was twelve years in prison, and it is easy to suggest why specifically twelve since, after all, Joseph had a total of twelve siblings (including Dinah). The Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 84:7) further emphasizes God’s exacting punishment:

“Joseph brought evil report of them to their father” – what did he say? Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda, and Rabbi Shimon [taught]: Rabbi Meir says [that Joseph would report]: “Your sons are suspected of eating the limb of a living animal.” Rabbi Shimon says: “They are directing their gaze at the girls of the land.” Rabbi Yehuda says: “They are demeaning the sons of the maidservants [Bilhah and Zilpah] and calling them slaves.”

Rabbi Yehuda bar Simon said: He was punished for all three of them, for “Balances and scales of justice are Hashem’s…” (Proverbs 16:11) The Holy One, blessed be He, said to him: “You said: ‘Your sons are suspected of eating the limb of a living animal.’ As you live, even at their time of corruption, they will slaughter and only then will they eat [as it is written:] ‘and slaughtered a goat.’ (Genesis 37:31) You said: ‘They are demeaning the sons of the maidservants and calling them slaves.’ [And so,] ‘Joseph was sold as a slave.’ (Psalms 105:17) You said: ‘They are directing their gaze at the girls of the land.’ As you live, I will incite the same against you [as it is written,] ‘His master’s wife cast her eyes [upon Joseph, and she said: Lie with me.]’” (Genesis 39:7)

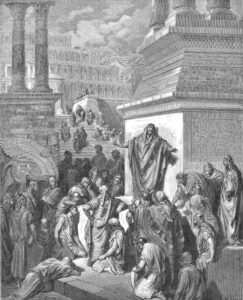

‘Joseph Makes Himself Known to His Brethren’ by Gustav Doré

One thing that we learn from this is that the brothers of Joseph were not all that wrong in being suspicious of him, and perhaps even wanting to rid of him. He did have a dangerously large ego, and we go on to read in the Torah how Joseph consolidated more and more power in Egypt, eventually enslaving the entire Egyptian populace (Genesis 47). It isn’t surprising that the angry and subdued Egyptians later turned the tables and enslaved the Israelites! Because of this need to dominate, the Zohar (I, 200a) says Joseph was not given his own flag among the Tribes. The Zohar points out there was no degel machane Yosef, but only a degel machane Ephraim. The flag of Joseph was replaced with the flag of his son, serving as something of a “demotion” due to Joseph’s desire for superiority. The Talmud (Berakhot 55a), meanwhile, points out that Joseph was first to die among his brothers for similar reasons of ego.

Now, all of this is not to take away from Joseph’s righteousness. After all, he is called Yosef haTzadik, the epitome of righteousness, and embodied sexual purity, restraint, and great wisdom. Nonetheless, no one is perfect, and the Torah highlights the flaws of its heroes so that we can learn from them. The Torah was given to guide us in refining ourselves and becoming better people; to teach us that God is merciful and longsuffering, giving us many opportunities to repent and rectify, even across multiple lives and eras.

In fact, Joseph was reincarnated in his descendant Joshua, the humble servant of Moses (see Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, Letter Mem). Both Joseph and Joshua are described in the Torah as being filled with a Godly spirit, and both died at the exact same age of 110 (see Genesis 50:26 and Joshua 24:29). Joseph was the reason the brothers came down to Egypt in the first place and ended up staying there “in exile” for centuries, so fittingly it was Joshua that brought the Children of Israel back into the Holy Land. Humble Joshua—who spent the first part of his life enslaved to the Egyptians—was the rectification for haughty Joseph. And the final incarnation of that soul is in Mashiach ben Yosef (Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, Letter Pei), to once more bring all the Children of Israel back to the Holy Land at the End of Days, and usher in a better world for all mankind.

Shabbat Shalom and Happy Chanukah!

Chanukah Learning Resources:

Chanukah’s Electrifying Secret (Video)

Chanukah & the Light of Creation (Video)

Did the Jews Really Defeat the Greeks?

When Jews and Greeks Were Brothers

Death of Hellenism, Then and Now

Rabbi Akiva and the Maccabees

Where in the Torah is Chanukah?