‘Deborah’ by Gustav Doré

This week’s parasha, Tetzave, continues with the description of the construction of the Mishkan and its holy vessels. The walls of the Mishkan were held up by 48 pillars of acacia wood, plus 7 lintel beams. The Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) comments on Exodus 26:15 that the 48 pillars correspond to the 48 male prophets named in Tanakh. The 7 lintels, meanwhile, correspond to the seven generations between Abraham and Moses. This second comment is strange since we would expect the Ba’al haTurim to instead say that the 48 pillars correspond to the 48 male prophets while the 7 lintels correspond to the 7 female prophetess, as enumerated by our Sages. We are taught in the Talmud (Megillah 14a) that the Seven Prophetesses of Israel were Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther. Of course, there were other female prophetesses in ancient Israel, just as there were many more than 48 male prophets. These 55 are specifically mentioned because we actually have their prophecies recorded, or because they are explicitly referred to as “prophets” in Tanakh (as Miriam is in Exodus 15:20).

The Seven Prophetesses are particularly special because they are sometimes described as being even greater than their male counterparts. For instance, when Abraham turned to God concerned about Sarah’s plans, God told him to listen to Sarah and do as she says (Genesis 21:12). Deborah is described as being greater than Barak, and Hannah more in tune than Eli the kohen gadol. Amazingly, Rav Yitzchak Ginsburgh points out that when the Torah says there will be more great prophets in the future like Moses to lead the people (Deuteronomy 18:15), the gematria of that entire phrase (נָבִיא מִקִּרְבְּךָ מֵאַחֶיךָ כָּמֹנִי יָקִים לְךָ יהוה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֵלָיו תִּשְׁמָעוּן) is 1839, exactly equal to the value of the names of the Seven Prophetesses! (שָׂרָה מִרְיָם דְּבוֹרָה חַנָּה אֲבִיגַיִל חֻלְדָּה אֶסְתֵּר) That might explain why the 7 lintels lie “above” the 48 pillars, as if implying that the female prophetess were greater than the male ones. What exactly was so great about them?

Sarah’s prophecies ensured that Isaac would inherit the covenant and continue the divine line started by Abraham. Miriam inspired her parents to reunite after their separation, resulting in the birth of Moses. She later guided baby Moses in the river and ensured his survival. There would be no Moses without Miriam! Deborah saved Israel from the cruel subjugation of Sisera, and composed one of history’s ten divine songs. From Hannah we learn how to pray (Berakhot 30b-31b), and Abigail taught us about the afterlife (including terms like kaf hakelah and tzror hachayim). Huldah foresaw the destruction of Judah at the time of King Yoshiyahu (and it is possible this prophecy resulted in the pre-emptive move to save the Ark of the Covenant and hide it for the distant future). Esther saved the Jewish people from near-extinction, and produced one of the 24 books of Tanakh.

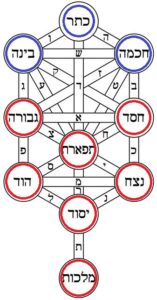

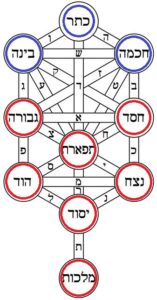

The Sefirot of “Mochin” above (in blue) and the Sefirot of the “Middot” below (in red).

We can further parallel the Seven Prophetesses to each of the seven lower Sefirot (as all things seven in Creation are connected, and emerge from the lower Seven). Miriam embodied the waters of Chessed, taking care of her little brother, nurturing him as an infant, and later providing all the Israelites with water in the Wilderness through her miraculous well. It is specifically by the waters of the Red Sea that the Torah calls her a prophetess. Sarah, on the other hand, was Gevurah, representing severity and judgement. She made the tough call to expel Hagar and Ishmael. While Abraham was the man of Chessed, Sarah was clearly his Gevurah counterpart. (In the next generation it was flipped, with Isaac embodying Gevurah and his wife Rebecca representing Chessed—introduced in the Torah as carrying a water jug on her shoulders and kindly providing abundant waters to the camels of Eliezer.) Deborah was the judge and Torah scholar, the greatest halakhic authority of her day, personifying Tiferet, the source of Torah and emet, “truth”.

Abigail taught us about eternal life—the eternity of Netzach. She introduces us to the transmigrations of the soul following death, calling it kaf hakelah, which the Zohar (II, 99b) explains means that the soul is flung from one body to another, from one reincarnation to another, like a stone flung from a sling. The Arizal (Rabbi Itzhak Luria, 1534-1572) gives the same explanation for kaf hakelah in Sha’ar haGilgulgim (Ch. 22). Incredibly, he reveals that Abigail was herself a reincarnation of Leah! (Ch. 36) Her original husband Naval was a reincarnation of Lavan, while David had a spark of Jacob. Just as Jacob worked for Lavan, David worked for Naval. And just as Lavan cheated Jacob out of his wages, Naval did the same to David. The tikkun here was that Jacob did not wish to marry Leah, and she always felt secondary and unloved. This was rectified with Abigail, as David did indeed wish to marry her and gave her the attention she deserved. Nor was there any trick in getting David to marry Abigail, which is what had happened previously with Lavan tricking Jacob into marrying Leah.

Hannah taught us lehodot, to acknowledge Hashem and to be grateful. She sang a majestic prayer-song of thanksgiving. This is, of course, the Sefirah of Hod. The result of her prayers was Samuel, who went on to anoint the first kings of Israel. Huldah foresaw the destruction of Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah due to the violation of the covenant, the brit associated with foundational Yesod. She lived in Jerusalem (II Kings 22:14), the place of the “Foundation Stone”, even hashetiyah. In fact, the southern wall of the Temple Mount has an ancient gate referred to as the “Huldah Gate”. Huldah also relayed to King Yoshiyahu that he will be spared destruction and die in peace (II Kings 22:20) because of his genuine teshuvah and rectification of his brit. The Talmud (Megillah 14b) says Huldah was a descendant of Rahav, who had an immoral past and rectified her own sphere of Yesod, meriting to marry Joshua and become the mother of many great prophets and figures, including Jeremiah and Neriah.

Finally, Esther is the embodiment of a queen, the final “feminine” Sefirah of Malkhut. In fact, the word “Malkhut” appears ten times in the Megillah, more than in any other book of Tanakh! And we read in Esther 2:17 that “The king loved Esther more than all the other women… so he set a royal crown [keter malkhut] on her head and made her queen…” Recall the teaching of our Sages that when the Megillah mentions “the king” without a name or qualifier, it can also be read as referring to The King, to Hashem. And so, it is as if God Himself crowned Esther with Malkhut.

In these ways, the seven lower Sefirot parallel the Seven Prophetesses, who attained divine inspiration on the highest levels, and ensured the survival of Israel and Judaism throughout the centuries.