One of the most common questions that people ask about the Exodus is: where is the evidence? The truth is that there is a great deal of evidence supporting the subjugation and liberation of the Israelites from ancient Egypt. Much of the evidence has been deliberately suppressed (as explained here), and other pieces of evidence are just not discussed or not well-known. Perhaps the greatest of the latter variety is the Mose Stele. This incredible archaeological find is possibly the best proof that we have of the existence of Moses, and the details of his unique life.

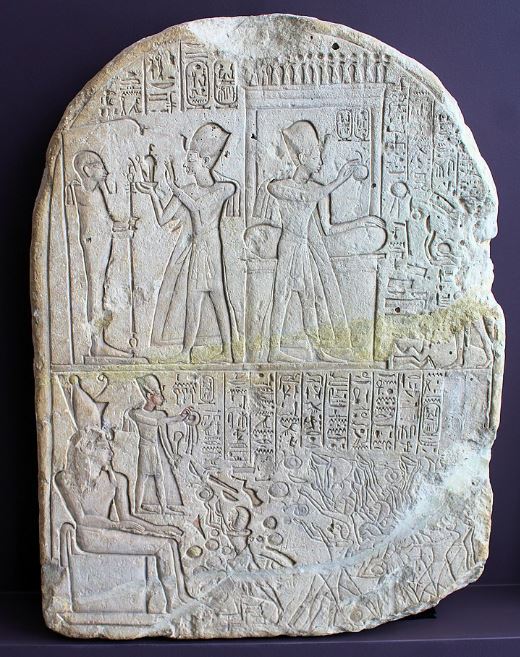

The Mose Stele, currently housed in the Roemer und Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, Germany.

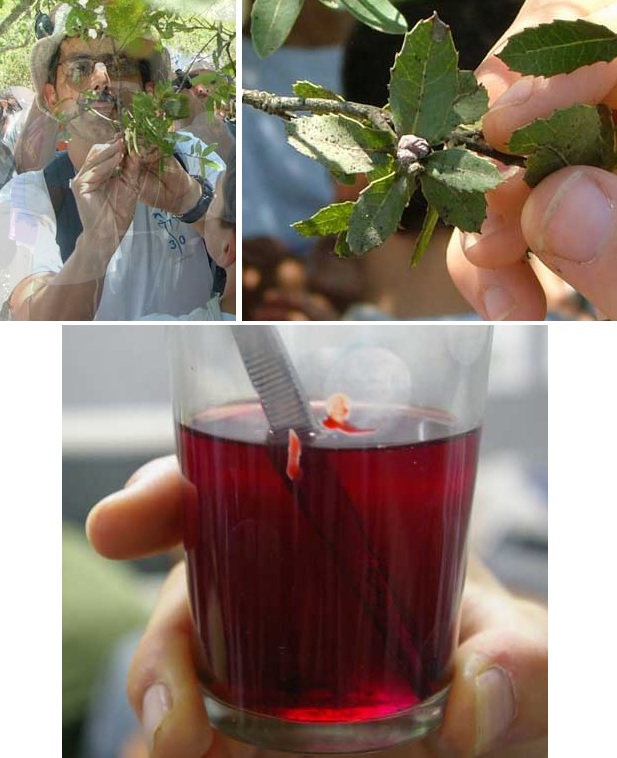

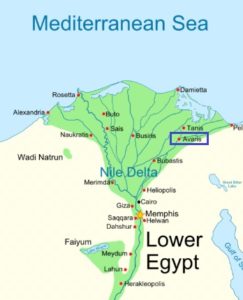

The Mose Stele was found in the village of Qantir, just two kilometres away from the ancient Egyptian city of Pi-Ramesses. The Torah states explicitly that the Israelites built the city of Pi-Ramesses (Exodus 1:11). We know that Pi-Ramesses was built atop the more ancient city of Avaris, which was actually a Hyksos city. Recall that the Hyksos were Semitic foreigners who migrated to Egypt and, at one point, even took over much of the kingdom. Excavations at Avaris (in the northeast of Egypt, a region the Torah calls “Goshen”) show architecture in Canaanite and Syriac style. Amazingly, archaeologists have even found numerous seals bearing the name “Yaqub”.

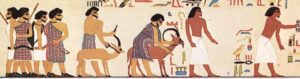

For these reasons, among others, scholars both ancient and modern believe that the Hyksos and the Israelites are one and the same. Already two millennia ago, Josephus identified the Hyksos (which he translated as “shepherd kings”) as the Israelites. If not completely one and the same, it is also highly possible that the Israelites were part of a larger wave of Semitic migration, and were initially a small group among the Hyksos. Whatever the case, the Hyksos as a whole were officially defeated by Pharaoh Ahmose I, who established the 18th dynasty around 1550 BCE.

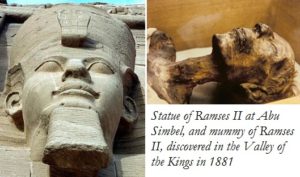

The following dynasty, starting in 1292 BCE, was founded by Ramesses I. His grandson was Ramesses II, the Great (r. 1279-1213 BCE), who ruled for a whopping 66 years. It was Ramesses II who built Pi-Ramesses and made it his new capital, and it is Ramesses II who is typically identified as the pharaoh of the Exodus. This is disputed for several reasons, including that the timing of Ramesses’ reign is both too long after the Hyksos defeat and a bit too late to fit with traditional Jewish chronology (which holds that the Exodus was in 2448 AM, or 1312 BCE). However, Ramesses’ reign is quite close to the Jewish dating and the chronology of ancient Egypt is not exactly known and may very well have discrepancies.

One of the artifacts that we have from the time of Ramesses II is the Mose Stele. It describes a great general in Ramesses’ army. The general’s name is Mose (hence the name of the stele). In ancient Egyptian, this word simply meant a “son” or “begotten by”. Ramesses, for instance, means “son of Ra” or “begotten by Ra”, Ra being the sun god and one of the chief deities of the Egyptian pantheon. We find many Egyptians with mose or mses as a suffix in their name, including Ahmose, Thutmose, and countless others. “Mose” would just mean “son”, which is strange at first glance, since it carries no qualifying prefix. However, it makes perfect sense when we go to the Torah and remember that the daughter of Pharaoh adopted baby Moses and named him. While the Torah says she named him Moshe because she took him out (meshitihu) of the water (Exodus 2:10), it is highly unlikely that an Egyptian princess would give the baby a Hebrew name. She would have named him Mose, in Egyptian, meaning the long-awaited “son” she always wanted. Moshe is indeed his true Hebrew name, as God intended, which is why the Torah records the proper Hebrew etymology. Of course, in Hebrew both Moshe and Mose would be spelled exactly the same anyway (משה), since the shin and sin are one letter with interchangeable sound. Thus, he could simultaneously be “Moshe” to his Hebrew brethren, and “Mose” for his fellow Egyptian royalty among whom he grew up!

The Mose Stele says that Mose was a victorious soldier, and Ramesses is shown lavishing gifts upon him. Ramesses declares: “How good is what he has done! Great, great!” Was the Biblical Moses a soldier? The Torah doesn’t quite say so explicitly, but the Talmud and Midrash do describe Moses as a warrior in several places. The most famous is where Moses is described participating in the battle against Og, and smiting the giant himself (Berakhot 54b). Lesser known is the Midrash that says Moses was once a great general in the land of Cush (see, for instance, Yalkut Shimoni I, 168). This is how he ended up marrying a Cushite woman, as the Torah later mentions in Numbers 12:1 (for more on this see ‘Did Moses Have a Black Wife?’) While the Midrash generally assumes that this happened after Moses fled Egypt and before he came to Midian, Josephus provides an alternate account that says Moses fought in Cush while still an Egyptian prince (Antiquities, II, 10:239). Before he fled, Moses was a highly decorated general in the Egyptian army, and helped the Egyptians subdue their Cushite neighbours.

The Mose Stele fits perfectly with Josephus’ ancient account. Moses returns from battle with Cush as a victorious general, and is praised by Ramesses. The stele adds that Mose is “beloved of Atum and greatly favoured by him”. Atum was none other than the Egyptian creator god, the first of their gods, and the originator of all the others. It is fascinating to note that while Ramesses’ patron god was Ra, the stele describes Mose as being favoured by Atum, not Ra. We can learn from this that Moses was already something of a monotheist among the Egyptian royalty: he made sure that they knew he worshiped only the one true creator God. For the Egyptians, the closest thing to that was Atum! This is how Moses could have masked his Hebrew beliefs while growing up with idolaters in the palace.

There is one last connection to Moshe in the Mose Stele. Ramesses is quoted as saying that he is “pleased with the speech of [Mose’s] mouth”. The Torah tells us that Moses was “heavy” of speech, and Moses himself humbly sought to shy away from oration. The fact that the stele mentions the speech of Mose is unlikely to be a coincidence. Perhaps Ramesses put it there specifically to address the critiques of others who disparaged Moses for his speech difficulties. Moses silenced his critics, and Ramesses declared that he is pleased with the speech of Moses, despite what others might say.

All in all, the Mose Stele is an amazing piece of evidence that strongly supports the existence of the Biblical Moses. It was likely commissioned by Ramesses II while Moses was still a young Egyptian prince and general, before he fled, and long before he returned decades later to liberate his people. We can imagine that after the events of the Exodus, the angry Egyptians would have destroyed any mention of Moses, and would have tried to expunge any relic of his name or life. Thankfully, at least one piece of evidence has nonetheless survived, buried and hidden away for millennia. What other incredible treasures are still lying deep under the sand, waiting to be uncovered?

For more on dating the Exodus and finding scientific evidence, see Did the Jews Build the Pyramids?