‘Sukkot in the Synagogue’ by Leopold Pilichowski (c. 1894)

As we continue to celebrate Sukkot this week and “shake” our arba’at haminim, it is worth exploring the properties of these unique four species. One of the intriguing things about them is that they all happen to be prominent players in medicine. Perhaps most well-known is the bark and leaves of the willow tree (the aravot of the four species), which is the original source for what is today aspirin. The active ingredient in aspirin is acetylsalicylic acid, a synthetic variant of salicylic acid found in high quantities in willow trees. Incredibly, archaeologists have found that teas made from willow were used medicinally as far back as ancient Sumeria (birthplace of Abraham) and ancient Egypt. The ancient Greeks used it to bring down fevers, and it was a staple medicine among Native American tribes.

It was in 1853 that French chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt first synthesized acetylsalicylic acid in the lab. The problem was that these types of medicines were very hard on the stomach. In 1897, a Jewish chemist named Arthur Eichengrün, working for Bayer, invented a new process for producing and purifying acetylsalicylic acid. This one was much easier on the stomach and worked extremely well. Thus, aspirin as we know it was born, and is today the most widely-used drug in the world. Things didn’t turn out so well for Eichengrün, though. When the Nazis came to power, they could not tolerate a Jewish inventor for aspirin, so they wiped his name from the history books and instead made sure to credit German scientist Felix Hoffman with the invention. Eichengrün was arrested and sent to a concentration camp. Thankfully, he survived the Holocaust. Altogether, Eichengrün held 47 patents, and also invented Protargol, which was the standard treatment for gonorrhea for over 50 years.

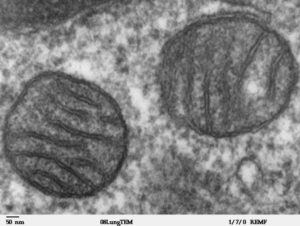

The way that acetylsalicylic acid actually works in the body was only discovered in 1971. It’s main mode of action is by blocking a family of enzymes called cyclooxygenases (COX), key players in the inflammatory pathway. By inactivating these enzymes, aspirin is able to reduce pain and inflammation. It also helps to block the formation of blood clots. More recently, acetylsalicylic acid has been shown to help improve the function of mitochondria—those tiny organelles within each of our cells that powers our bodies.

One of the main uses of aspirin today is to help treat and prevent heart attacks and heart disease, which is the world’s number-one killer. The main cause of heart disease is poor diet, particularly high cholesterol and saturated fats, as well as high sodium which increases blood pressure. Another major cause is smoking. Fittingly, our Sages taught that the aravot parallel the mouth, and resemble the shape of the lips. The purpose of the aravot is to both spiritually rectify the sins of the mouth, as well as to remind us to control what goes in (and out) of our mouths. We ask every morning in birkot haTorah that God should make words of Torah “pleasant-tasting” in our mouths (וְהַעֲרֶב נָא יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֵֽינוּ אֶת־דִּבְרֵי תוֹרָתְךָ בְּפִֽינוּ) and this ties directly to the mouth-like aravot (ערבות). We should increase the use of our mouths for words of Torah, and decrease its use for the oral vices that end up harming people.

Myrtle Leaves

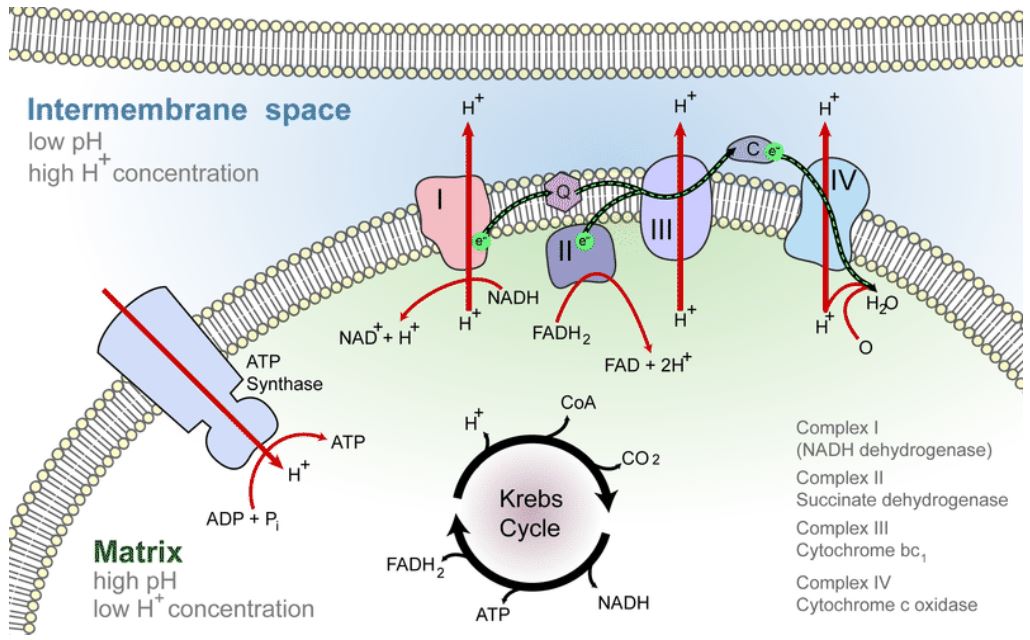

The other leaves in the four species, myrtle or hadassim, also happen to contain high amounts of salicylic acid. Additionally, they are rich in various antioxidants. Those mitochondria mentioned above use the oxygen we breathe in the production of energy. More specifically, producing the energy molecule ATP requires the movement of hydrogen ions. To keep those hydrogen ions moving in the right direction, oxygen comes in to bond with them, and pick up a pair of electrons, too, generating water. This is the main reason for why we need to breathe! The primary role of oxygen in the human body is to be an “electron acceptor”, picking up some electrons and some hydrogens so that energy production can continue.

The Electron Transport Chain within the mitochondria in our cells produces most of our energy. Water is generated at Complex IV, where oxygen comes in to serve as the final electron acceptor. Energy (in the form of ATP) is produced at the Synthase pump, driven by the movement of hydrogen ions.

In this process, however, sometimes the oxygen molecules don’t bond properly, and form dangerous “reactive oxygen species”, or “oxidants”. These free radical oxidants can attack other structures within the cells, causing cellular damage and “oxidative stress”, strongly linked to aging and cancer. Thus, we need anti-oxidants to neutralize these troublesome free radicals. This is why you might see “antioxidants” advertised on the labels of health foods, cosmetics, and other commercial products. The leaves of hadassim naturally contain very high levels of antioxidants.

Throughout history, myrtle leaves have been used medicinally. Today, they have two main uses: One, the essential oil of myrtle is used in aromatherapy and to treat lung illnesses. Myrtle helps to open up the airway and reduce inflammation in the lungs. Second, it is used to treat and help prevent the spread of HPV, a sexually-transmitted disease. It is interesting to point out that our Sages paralleled the hadassim to the eyes. As we read in the Shema, God warns us not to follow after the lustful desires of the heart, which follow the eyes that are easily enticed by inappropriate sights and images. The Torah specifically uses the word zonim, implying sexual immorality, which begins with inappropriate sight. Thus, the use of myrtle leaves in treating sexually transmitted diseases is all the more appropriate!

Date Palms

The kapot tamarim, or lulav, is the “spine” of the date palm, and our Sages paralleled it to the spinal cord of the human. Both the fruit of the tree, and the “hearts of palm” of the lulav are highly nutritious. Their high fibre content was historically used to treat constipation. Recall that the Rambam held constipation to be a major root of poor health, writing in the Mishneh Torah that “Whoever sits comfortably and takes no exercise, holds his waste or has ‘hard’ innards, even if he eats all the best foods and follows the top medicine, all his days will be full of pain and his strength will decline.” (Hilkhot De’ot 4:14-15)

Mitochondria under a microscope.

In ancient Israel, the date palm was the source of honey. As is well-known, when the Torah speaks of Israel being a land flowing with “milk and honey”, it is referring to date honey, not bee honey. Honey is about 80% sugar, our body’s main energy source. In fact, those electrons in the mitochondria mentioned above, which drive the “electron transport chain” to produce our ATP energy, are extracted from sugar! We now see how the main ingredients in aravot, hadassim, and lulav all play a big role within our mitochondria, driving our biological life force.

Dates are also very rich in potassium—50% more than in bananas! Potassium ions play the most important role in the transmission of nerve signals. Every nerve conduction requires an exchange of sodium and potassium. So, it is appropriate that the lulav is compared to the spinal cord, the most important bundle of nerves in the body. Sefer haBahir, one of the most ancient mystical texts, states that not only does the lulav parallel the spinal cord, it also parallels the letter nun sofit (ן), which resembles a spinal cord. The value of the nun is 50, alluding to the 50 Sha’arei Binah, “Gates of Understanding”.

Etrog

Finally, we have the citrus etrog. As expected, it has a very high vitamin C content, typically considered the most important vitamin in the body. The greatest champion of vitamin C was Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling. (Pauling is actually one of just four people to win two Nobel Prizes!) He was also ranked the 16th greatest scientist of all time. It was Pauling who first proposed that vitamin C can combat cold and flu infections. He later took it further and suggested vitamin C as a cure for all kinds of ailments, including cancer. His main work was in using vitamin C to treat heart disease and angina. Today, this method is still referred to as Pauling Therapy, though it remains controversial. Nonetheless, it is quite fitting since, of course, our Sages stated that the etrog parallels the heart!

Finally, we have the citrus etrog. As expected, it has a very high vitamin C content, typically considered the most important vitamin in the body. The greatest champion of vitamin C was Nobel Prize-winner Linus Pauling. (Pauling is actually one of just four people to win two Nobel Prizes!) He was also ranked the 16th greatest scientist of all time. It was Pauling who first proposed that vitamin C can combat cold and flu infections. He later took it further and suggested vitamin C as a cure for all kinds of ailments, including cancer. His main work was in using vitamin C to treat heart disease and angina. Today, this method is still referred to as Pauling Therapy, though it remains controversial. Nonetheless, it is quite fitting since, of course, our Sages stated that the etrog parallels the heart!

The other known medicinal use of the etrog (or “citron”, in English) is as an antibiotic. Specifically, it is the rind of the etrog which is thought to contain strong antibiotic properties. This would help to explain why the Torah calls the etrog a pri etz hadar, one of the classic explanations of which is that it is a “long-lasting” fruit that doesn’t spoil quickly. Spoilage is caused by a number of factors, one of which is the proliferation of bacteria. By containing an antibiotic in its rind, the etrog stays fresh much longer than other fruits.

Related to this is that the etrog has an insecticide property. The ancient Greek scholar Theophrastus (c. 371-287 BCE) wrote that it was common to keep etrogim around clothes to repel moths and bugs. Similarly, Pliny the Elder (c. 23-79 CE) wrote in his Natural History that the etrog “is very useful in repelling the attacks of noxious insects.” (A useful tip for those of us who have to deal with wasps and mosquitos in the sukkah!) This is yet another reason for the etrog remaining fresh and long-lasting. Both Theophrastus and Pliny note how the etrog bears fruit all year round, which ties to the final reason for why the etrog is identified as the Torah’s enduring pri etz hadar. Lastly, Pliny mentions that pregnant women would chew on etrog seeds to prevent morning sickness and nausea, fitting neatly with the notion that the etrog is a potent segulah for fertility.

In short, just as the four species are physically healing, they are even more so spiritually healing. As the Zohar famously states, this lower material world is only a reflection of the higher spiritual worlds. Thus, if the four species have potent medicinal and chemical properties in this lower world, their root in the spiritual realms must be all the more powerful and effective. Something to keep in mind as we fulfil each day of Sukkot the mitzvah of netilat lulav.

Chag Sameach!