‘Two ancient Jewish sages studying and ascending to Heaven’ an image generated for me (in just seconds!) by Midjourney AI (Artificial Intelligence) software.

The Talmud famously quotes the sage Rava as teaching that one should imbibe wine on Purim ad d’lo yada, until one does not know the difference between “cursed is Haman and blessed is Mordechai” (Megillah 7b). This is a bizarre statement, because a Jew is never supposed to be so heavily under the influence. Indeed, the Talmud continues right after to tell a story of how one Purim, that same sage Rava got so drunk that he seemingly “killed” Rabbi Zeira! All was well though because, great sage that he was, Rava resurrected Rabbi Zeira back to life. The short passage ends by saying that the following year, Rava invited Rabbi Zeira to another Purim feast, and Rabbi Zeira politely declined, saying “miracles don’t happen all the time!” Nothing more is said, leaving the reader scratching his head. What really happened between Rava and Rabbi Zeira?

The simplest reading suggests that the Talmud is trying to disqualify Rava’s opinion. It was Rava who suggested that one should get really drunk, so the Talmud right after describes how Rava himself got so drunk that he ended up murdering someone. Lesson: don’t get drunk on Purim! More ironic still, it was Rava who taught, elsewhere, that one shouldn’t even look at wine, since consuming wine could lead to bloodshed! (Sanhedrin 70a) It is most likely that he only taught this after that infamous Purim incident, when he learned his lesson.

The simple solution above works, but doesn’t answer the big mysteries: why did Rava phrase his teaching that one should not know the difference between Haman and Mordechai? To not be able to differentiate at all between good and evil seems almost impossible, even when totally under the influence. Second, how could a tremendously righteous and wise rabbi like Rava kill another person? This, too, seems impossible, even if he was completely drunk. Finally, if Rava had the power to resurrect another person, why did Rabbi Zeira fear to celebrate Purim with him the following year? Surely Rava wouldn’t make the same mistake again, and even in the extremely unlikely event that he did, couldn’t Rava just revive him once more anyway? To solve these problems, we have to look deeper.

As discussed in the past (see ‘The Secret Behind Wearing Masks and Getting Drunk’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two), the real reason to drink wine on Purim is only to be able to understand Torah on a more profound level. One of the effects of alcohol is that it increases levels of (and/or acts like) the neurotransmitter GABA, an inhibitor which shuts things off in the brain. When one drinks a little bit, GABA starts to shut down processes in the outer cortex and prefrontal cortex of the brain. This includes things like motor function, decision-making, and analysis, which serves to remove various inhibitions and restraints one has, often making a person “softer”, more open and more loving, and able to see things as being more attractive. When applied to Torah, a little bit of wine can help a person notice things they never did before, or come to new realizations. Indeed, GABA is also associated with the formation of new neural connections. And, with their normal analytical mind suppressed, a person may be able to think differently than their usual modes of reasoning, opening up the possibility to chiddushim. (With too much alcohol though, GABA levels start to go up deeper and deeper into the brain, and if it gets all the way to the brain stem—which controls vital functions like breathing—it can become fatal.)

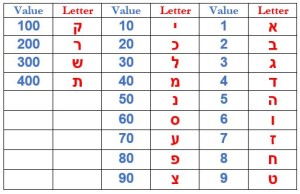

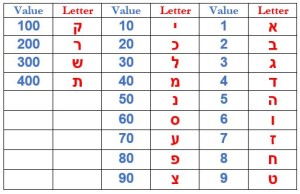

This explains why Rava would teach that drinking wine in moderation can make a person wise (Sanhedrin 70a). Our Sages similarly taught that nichnas yayin, yatza sod: when one drinks wine, “secrets come out” (Sanhedrin 38a). The traditional way to understand this statement is that a person who drinks alcohol is likely to run their mouth and reveal embarrassing secrets. On a deeper level, however, it means that a person who drinks a little bit of alcohol may be able to uncover some new Torah secrets. They may be able to see things on a more profound level. For instance, within the phrase nichnas yayin, yatza sod is a mathematical secret where the value of “wine” (יין) is 70, as is the value of “secret” (סוד). Seventy comes in and seventy comes out!

In the same way, when Rava taught that one should drink until they don’t know the difference between “cursed is Haman” (ארור המן) and “blessed is Mordechai” (ברוך מרדכי), he really meant to look beyond the surface and see that, in gematria, these two statements are exactly equal! (Both add up to 502.) Mordechai is the force of goodness that perfectly neutralized Haman’s evil. So, it’s not that Rava said a person should get smashed on Purim, he meant that a person should drink just enough to learn Torah better and uncover its secrets. With this in mind, we can understand what happened between Rava and Rabbi Zeira that fateful Purim.

Basic Gematria Chart

Ascending to Heaven

As we might expect, when two sages get together on Purim, they are not getting together simply to party. They surely used it as an opportunity to pursue a higher spiritual endeavour. Purim, like all holidays, is when spirituality is heightened and the Heavens are more accessible. What Rava sought to do, with Rabbi Zeira’s help, is nothing less than ascend to the upper worlds. There is a long tradition of a pair or group of sages getting together to accomplish such feats. Surely the most well-known is the story of the Four Who Entered Pardes:

The Sages taught: Four entered “the orchard” [pardes], and they are: Ben Azzai, and Ben Zoma, Acher, and Rabbi Akiva… Ben Azzai glimpsed and died, and with regard to him the verse states: “Precious in the eyes of the Lord is the death of His pious ones” [Psalms 116:15]. Ben Zoma glimpsed and was harmed, and with regard to him the verse states: “Have you found honey? Eat as much as is sufficient for you, lest you become full from it and vomit it” [Proverbs 25:16]. Acher “cut the saplings”. Rabbi Akiva came out safely. (Chagigah 14b)

Long before Rava and Rabbi Zeira, Rabbi Akiva led a group of four to ascend to the Heavenly “orchard”. Through various Kabbalistic means, the souls of the four wise men went up to the upper worlds, and the Talmud even describes some of the incredible things they saw. It was so shocking that Acher, previously known as Rabbi Elisha ben Avuya, “cut the saplings” and became a heretic. Ben Azzai’s soul never returned, while Ben Zoma went mad. Only Rabbi Akiva survived the experience and came out whole.

In his Ben Yehoyada, the Ben Ish Chai (Rabbi Yosef Chaim of Baghdad, 1835-1909) explains that this is precisely what happened to Rava and Rabbi Zeira! They were learning some really deep stuff and Rava was teaching Rabbi Zeira such great mystical secrets that his soul literally left his body and ascended heavenward. Rava was able to then draw Rabbi Zeira’s soul back down to this world and revive him. The Ben Ish Chai connects this to what happened at Mount Sinai, when the entire nation “died” and was “resurrected”, because God’s revelation was so intense. With this in mind, I believe we can properly understand why the Talmud uses a unique word in this passage:

Another version of ‘Two ancient Jewish sages learning Torah and ascending to Heaven’ generated by Midjourney AI

The standard Aramaic term for “killing” in the Talmud is katal (קטל). Yet here, the Talmud doesn’t use that word, but uses shecht (שחט) instead. This word is, of course, the one used in reference to the kosher slaughter of an animal, for meat consumption. So, what does it mean that Rava shechted Rabbi Zeira? We must remember that the purpose of shechitah is not to just kill the animal. Rather, shechitah is the mechanism through which the animal’s soul is able to return to Heaven. On a Kabbalistic level, it functions as a tikkun for the animal’s soul, allowing it to ascend upward. This is precisely what Rava did to Rabbi Zeira, by extracting the soul out of his body and elevating it to the upper worlds, giving him an “out-of-body” experience. I think this is the real reason the Talmud uses the term shecht!

To go back to our three starting questions: 1) Rava did not say one should be drunk out of their minds, rather he taught that one should drink a little wine in order to learn better and be able to unravel Torah secrets. 2) Rava never literally killed anyone, God forbid, but simply elevated the soul of Rabbi Zeira through the depth and breadth of his Torah teachings. 3) Rabbi Zeira did not wish to have another “out-of-body” experience with Rava the following year simply because he knew how perilous such a journey might be. After all, Ben Azzai’s soul was so happy up there that he never returned to Earth. So, it’s not so much that Rava wouldn’t be able to revive Rabbi Zeira again, but that Rabbi Zeira worried he might not wish to return!

It must be mentioned here that there is an alternate way to read the Talmud’s concluding words in this passage. Since the Talmud does not identify who the “he” is, some people read it to mean that it was Rabbi Zeira who asked for another Purim party with Rava—having had such an awesome experience the previous year—and it was Rava who declined, since he was not sure if he could revive Rabbi Zeira again! Whatever the case, we must remember that a Jew need not resort to chemical substances for spiritual elevation; Torah study itself can be far more potent.

Chag Sameach!