This Friday night we will be gathering to celebrate the holiday of Pesach. It will also be Shabbat, which is highly appropriate because Pesach and Shabbat are deeply intertwined. While Shabbat is mentioned multiple times in the Torah, there are two places in particular where Shabbat is commanded and explained: the two times that the Torah records the Ten Commandments. These two passages are nearly identical except for, primarily, the description of Shabbat. In the first account, Exodus 20, we read:

Remember the Sabbath day to keep it holy. Six days shall you labour, and do all your work; but the seventh day is a Sabbath unto Hashem, your God, in it you shall not do any manner of work; you, your son, your daughter, your servant, your maid, your cattle, and the stranger that is within your gates; for in six days Hashem made Heaven and Earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and He rested on the seventh day; therefore Hashem blessed the Sabbath day, and sanctified it.

In the second account, Deuteronomy 5, we read:

Observe the Sabbath day to keep it holy, as Hashem your God commanded you. Six days shall you labour, and do all your work; but the seventh day is a Sabbath unto Hashem your God, in it you shall not do any manner of work; you, your son, your daughter, your servant, your maid, your ox, your donkey, your cattle, and the stranger that is within your gates; that your servant and your maid may rest as well as you. And you shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and Hashem your God brought you out from there by a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm; therefore Hashem your God commanded you to keep the Sabbath day.

There is one striking difference between the two passages. In the first, the reason for keeping Shabbat is to remember Creation, since God created the universe in six days and rested on the seventh. In the second, the reason for keeping Shabbat is to remember the Exodus, and that we were once slaves that worked tirelessly seven days a week, and now that God has freed us from slavery we should make sure to take a day off. We must never be slaves again, nor are we allowed to enslave others, with God insisting that even our servants and maids “rest as well as you”.

From this alone, we see a strong link between Pesach and Shabbat. In fact, each Shabbat when we recite Kiddush we mention how it is both to commemorate maase Beresheet and yetziat Mitzrayim, both Creation and the Exodus. In the Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 10b), the Sages even debate when God had created the world: was it in Tishrei, or in Nissan, the month of the Exodus? And just as Shabbat is a “mini-Pesach”, Pesach is a “mini-Shabbat”. When the Torah commands counting the Omer, it says to being the count mimachorat haShabbat, “from the day after Shabbat”, which is actually referring to Pesach, when we begin the count (on the second night).

The Kabbalists explain that the events of Pesach and the Exodus rectified all of Creation. The Ten Plagues corresponded to the Ten Utterances of Creation, and each one was meant to repair a level of Creation that the Egyptians had tarnished. (See ‘The Ten Plagues: Destroying the Idols of Egypt’ in Garments of Light.) On a mystical level, the Pesach seder reflects this, too.

The Hand of God

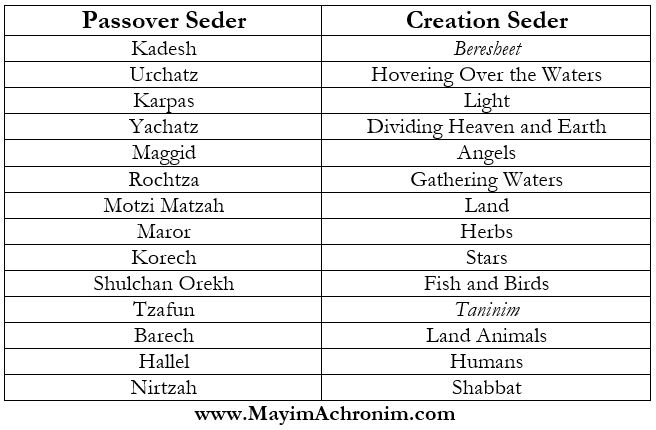

The seder has a total of fourteen distinct steps, easily remembered by the classic rhyme: Kadesh, Urchatz; Karpas, Yachatz; Maggid, Rochtza; Motzi Matzah; Maror, Korech; Shulchan Orekh; Tzafun, Barech; Hallel, Nirtzah. (Note that it is sometimes said that there are 15 steps to the seder, with Motzi and Matzah separated as two, even though they are one mitzvah of eating the matzah.) The fact that there are fourteen parts to the seder is not coincidental. The most common way, by far, that the Torah describes the Exodus is by saying God took us out of Egypt b’Yad chazakah, “with a strong Hand”. The term appears twelve times throughout the Tanakh. Additionally, we read of “God’s Hand” during the plague of pestilence (Exodus 9:3), and at the end of the account of the Splitting of the Sea:

And God saved Israel from the hand of Egypt [mi’yad Mitzrayim], and Israel saw the Egyptians dead upon the sea shore. And Israel saw the great Hand [haYad hagedolah] with which God acted in Egypt, and the people feared God; and they believed in God and in His servant Moses. (Exodus 14:31)

Altogether, we see the word yad used in metaphorical fashion fourteen times with regards to the Exodus, particularly in relation to God’s great “Hand”. And the gematria of yad (יד) itself is 14. I believe this is why the Sages specifically wanted to immortalize the seder with 14 steps.

Similarly, God created His universe with that same great “Hand”. When we look closer at the account of Creation, we find that there are a total of fourteen distinct actions associated with Creation itself:

First there’s “Beresheet”, which the Sages identify as the first Divine Utterance, the origin of time. Then God “hovered over the waters”, said to refer to the formation of the soul of Mashiach (see Ba’al HaTurim on Genesis 1:2, and Beresheet Rabbah 2:4). Then came (3) the creation of light, followed by (4) the division of the waters on the Second Day. On that same day, God created (5) various spiritual worlds, including the heavenly Gan Eden and Gehinnom, and populated them with all the Heavenly hosts and angels (See Yalkut Shimoni, chapter 1, passage 5, and Beresheet Rabbah 1:3). On the Third Day, God (6) gathered all the waters below, and (7) made the dry land appear, before (8) filling the earth with vegetation. Next came (9) the stars on Day Four, followed by (10) fish and birds on the Fifth Day. That day, there was an additional creation described in and of itself (11): “And God created the taninim hagedolim…” (Genesis 1:21). Then came the (12) land animals, (13) mankind, and lastly, (14) Shabbat.

All in all, we see fourteen clear steps in the account of Creation. It is worth mentioning here that in Hebrew the account of Creation (Genesis 1:1-2:4) was traditionally referred to as Seder Beresheet Bara. Creation is a “seder”, too. And we find very clear parallels between the fourteen parts of the Pesach seder and the fourteen steps of the Creation seder.

The Seder of the First Day

The first step of the seder is Kadesh, when we recite Kiddush and drink the first cup of wine. This officially ushers in the holiday and begins the seder process, just as the first act of Creation, Beresheet, officially started time and began the Creation process.

The next step is Urchatz, washing the hands with a cup of water. This first washing is done without saying the blessing al netilat yadayim. In Creation, the second verse tells us that God’s spirit “hovered over the waters.” The connection is self-explanatory.

Eating a vegetable (Karpas) is the third step and parallels the creation of light. As we’ve written in the past, the word “karpas” appears just once in the Tanakh, in describing the great banquet of King Achashverosh at the start of Megillat Esther. It refers to a certain fabric used in the drapery of the banquet. Mystically, it alludes to the fabric of Joseph’s special coat, which was dipped in blood and presented before Jacob to “confirm” the youth’s death. Jacob hence plunged into inconsolable grief and tears. We symbolically dip the karpas into salt water “tears”. That event—the sale of Joseph—led to the young man’s rise to power in Egypt, followed by his family’s settlement there, and then their enslavement, and finally the Exodus. So, that coat—karpas—set the events of the Exodus in motion. While the sale of Joseph was a sad and tragic event, Joseph himself insisted at the end that it was meant to be and all is well.

Eating a vegetable (Karpas) is the third step and parallels the creation of light. As we’ve written in the past, the word “karpas” appears just once in the Tanakh, in describing the great banquet of King Achashverosh at the start of Megillat Esther. It refers to a certain fabric used in the drapery of the banquet. Mystically, it alludes to the fabric of Joseph’s special coat, which was dipped in blood and presented before Jacob to “confirm” the youth’s death. Jacob hence plunged into inconsolable grief and tears. We symbolically dip the karpas into salt water “tears”. That event—the sale of Joseph—led to the young man’s rise to power in Egypt, followed by his family’s settlement there, and then their enslavement, and finally the Exodus. So, that coat—karpas—set the events of the Exodus in motion. While the sale of Joseph was a sad and tragic event, Joseph himself insisted at the end that it was meant to be and all is well.

Joseph is credited for possessing a good eye, and for always being able to see the good within each situation, no matter how terrible (this is why the Sages state that, in turn, the evil eye did not affect Joseph at all). This is the secret of the Light of the First Day. It is called Or HaGanuz, the “hidden light”, and is the light through which Tzadikim see the world. On a deeper level, it represents that hidden divine light concealed within all things. A person like Joseph can see beyond the external into the Godly light inside. Ultimately, the light of the First Day of Creation was preserved for the righteous in the World to Come (Chagigah 12a), who will bask in this divine light in their own Heavenly “banquet”, draped with hur karpas u’techelet, “white, pure, and blue fabrics” (Esther 1:6).

Becoming Angels

Step four in the seder is Yachatz, when the middle matzah is divided in half. This clearly corresponds to the next act of Creation, the division of the waters on the Second Day. On this day, God made a permanent separation between the “upper waters” (Heaven, or Shamayim in Hebrew, literally “waters there”) and the “lower waters” that cover over 70% of the Earth. The larger waters, the Heavens, were concealed by God, just as the larger piece of matzah from the Yachatz is concealed for the afikoman.

Next comes Maggid, when we relate the Exodus story. This corresponds to the other major event of the Second Day. Though not mentioned explicitly in the Torah, the Sages state that God populated the Heavens with angels on this day. Appropriately, the term maggid is actually used to refer to angels that communicate with people. Throughout history, multiple rabbis described how they received mystical secrets from Heaven through a “speaking angel”, a Maggid. The most famous example of this is Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575), the compiler of the Shulchan Arukh, who was visited by a Maggid and recorded some of these teachings in a book called Maggid Mesharim. An angel is first and foremost a messenger, and our job during the Maggid portion of the seder is to act as messengers in relaying the Exodus experience to our children.

Water, Land, and Passover Stars

After Maggid, we get up to wash netilat yadayim, this time with a blessing, because we then sit down to eat the matzah. We say the regular blessing of hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz, as well as the extra blessing al achilat matzah. These two steps, Rochtza and Motzi Matzah, parallel the next two steps of Creation (Genesis 1:9-10):

And God said: “Let the waters under the Heavens be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear.” And it was so. And God called the dry land “Earth” [eretz], and the gathering together of the waters He called “Seas” [yamim]; and God saw that it was good.

Washing the hands is an allusion to the gathering of the waters, and eating the “bread of the earth” (lechem min ha’aretz) alludes to the formation of the earth, eretz.

Right after this, still on the Third Day, God seeded the earth with various grasses, herbs, and vegetation. Needless to say, this corresponds to the next part of the seder, Maror, eating the bitter herbs.

Then comes the “sandwich”, Korech, a combination of matzah, maror, and charoset. As we read in the Haggadah, this step was instituted by Hillel, who would make a sandwich from the matzah, maror, and korban pesach, the Passover lamb, since the Torah explicitly states that the lamb should be eating al matzot u’merorim. Today, we don’t have the Passover lamb, but we do still make a korech. What does the Passover lamb have to do with the next act of Creation, the formation of stars?

Images of the constellation Ares, including a stylized version in the shape of a ram.

The Sages teach that God’s command to take sheep specifically was not without meaning. This is because the Egyptians were idol worshippers and astrologers, and the sheep was one of their main idols and astrological signs. In fact, this bit of astrology remains with us to this day, for the astrological sign of the month of Nissan (or April) is Ares, a constellation in the shape of a ram or sheep. God wanted us to barbeque sheep in particular to once again show the folly of the Egyptians’ idolatrous beliefs. God created the stars as chronological markers for “the holidays, days, and years” (Genesis 1:14), not for them to be worshipped.

Completing the Seder, Completing Creation

We now enter Shulchan Orekh, the great feast. We traditionally begin with eggs and fish. In fact, in olden days some had the custom to place an egg and fish on the seder plate itself (today we retain the egg, but not the fish). These represent what was created next, on the Fifth Day: fish and birds.

The Torah then states that God created taninim gedolim. There is much discussion about the identity of these mysterious creatures. Is the Torah speaking about whales (which, though in the seas, are not fish so they are listed as a separate creation)? Perhaps they are dinosaurs, since the most literal translation would be “large reptiles”? The Sages say that these actually refer to two great monsters or dragons (see Rashi on Genesis 1:21). God created a pair of them, male and female, but they were so terrible that He slayed one immediately afterwards so that the two wouldn’t reproduce. The remaining Leviathan is hidden away, perhaps prowling the deep seas.

‘Destruction of Leviathan’ by Gustav Doré

The taninim correspond to Tzafun, the consumption of the afikoman. The hidden half of the matzah is finally revealed and eaten to end the meal. This alludes to the meal at the End of Days, the so-called “Feast of Leviathan”, where the righteous will join Mashiach in partaking of the Leviathan’s flesh. (For more on the connection between Mashiach and the afikoman, see here.)

With the meal officially over, we recite Birkat Hamazon, and drink the third cup of wine with it. Our rabbis state that on holiday feasts one should especially partake of meat, which is the centrepiece of the holiday meal. (There is even a halachic debate whether one fulfils the mitzvah of a holiday meal if they did not consume meat, and another discussion of whether poultry is okay.) In Temple times, the major part of the meal was the roasted lamb itself. Having consumed our fill of meat, we say Barech to thank Hashem for it. This corresponds to the creation of land animals on the Sixth Day, without which we wouldn’t have the meat to begin with.

We then recite Hallel, to literally “praise” God. This corresponds to the creation of man, who was made for this very purpose. Unlike all other creations, man alone is capable of contemplating Hashem, serving Him, and connecting to Him.

Finally, there’s Nirtzah, where we declare our hope for the Final Redemption, and that next year we will be able to celebrate our complete freedom in Jerusalem. This is a wish for the coming of the great age at the End of Days that will be kulo Shabbat, an everlasting “Sabbath”. Of course, it parallels the final act of Creation: Shabbat.

In these ways, the Passover seder neatly parallels the seder of Creation. To summarize:

Chag Pesach Kasher v’Sameach!

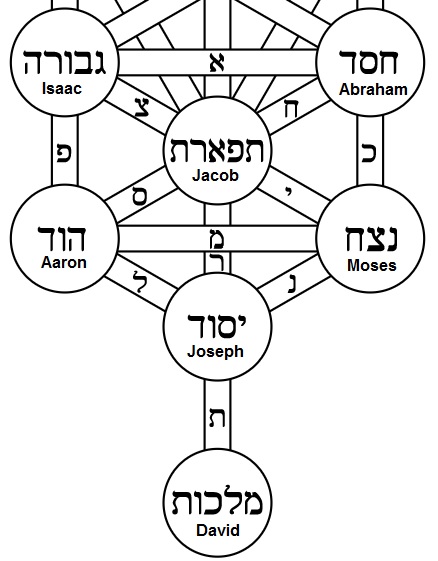

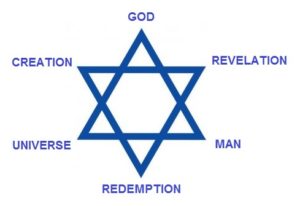

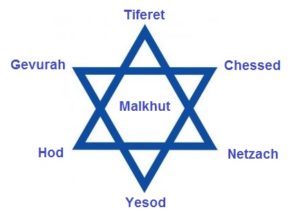

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.