The holiday of Passover commemorates the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt over three thousand years ago. The Torah tells us that because of their hasty departure, the dough of the Israelites did not have time to rise, hence the consumption of matzah. Yet, the term matzah appears in the Torah long before the Exodus! We read in Genesis 19:3 that Lot welcomed the angels into his home and “made them a feast, and baked matzot, and they ate.” Since the angels came to Lot immediately after visiting Abraham and Sarah to announce the birth of Isaac at that time next year (Genesis 18:10), the Sages learn from this that Isaac was born on Passover. Of course, the Exodus only took place four hundred years after Isaac’s birth! How is it that the patriarchs are already eating matzah?

The holiday of Passover commemorates the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt over three thousand years ago. The Torah tells us that because of their hasty departure, the dough of the Israelites did not have time to rise, hence the consumption of matzah. Yet, the term matzah appears in the Torah long before the Exodus! We read in Genesis 19:3 that Lot welcomed the angels into his home and “made them a feast, and baked matzot, and they ate.” Since the angels came to Lot immediately after visiting Abraham and Sarah to announce the birth of Isaac at that time next year (Genesis 18:10), the Sages learn from this that Isaac was born on Passover. Of course, the Exodus only took place four hundred years after Isaac’s birth! How is it that the patriarchs are already eating matzah?

An Eternal Torah

Although the Torah was given to the Israelites following the Exodus, Jewish tradition affirms that the Torah is eternal, and even predates existence. A famous verse in the Zohar (II, 161a) states that “God looked into the Torah and created the universe.” Adam knew the whole Torah, and was taught its deepest secrets by the angel Raziel. Many of these teachings were passed on by Adam to future generations, down to Noah, then his son Shem, and eventually to the Patriarchs who, according to tradition, studied at Shem’s academy. So, while the Torah tradition officially dates back to Sinai, in some ways it dates back all the way to Creation! It’s also important to keep in mind that the Patriarchs were prophets, which means that even though they did not have a physical, written Torah, there is no reason why they could not have received the Torah’s wisdom directly from God.

As such, it is said that the Patriarchs kept the entire Torah and fulfilled all the mitzvot. When Jacob sends a message to Esau after his sojourn in Charan he tells him “I have lived [garti] with Laban” (Genesis 32:5). On this, Rashi says that garti (גרתי) is an anagram of taryag (תרי״ג), the 613 commandments, meaning that despite living under the oppressive Laban for twenty years, Jacob still observed all 613 commandments. Yet, this is impossible since Jacob married two sisters—a clear Torah prohibition! Similarly, when Abraham meets Melchizedek (ie. Shem) following his victory over the Mesopotamian kings, he tells him that he will not take any reward whatsoever, not even “a thread or strap” (Genesis 14:23). For this, the Sages say, Abraham’s descendants merited the mitzvah of tzitzit (the threads) and tefillin (the straps). In that case, Abraham himself did not wear tefillin or tzitzit. From such instances we see that the patriarchs did not keep the Torah completely, at least not the Torah as we know it.

Emanations of Torah

While Kabbalistic texts often point out that the Torah is eternal and served as the very blueprint of Creation, they also go into more detail to explain that this primordial Torah was not quite the same as the Torah we have today. Each of the four mystical universes (Asiyah, Yetzirah, Beriah, Atzilut) has an ever-more refined level of Torah, with the highest being the Torah of Atzilut. Our Torah is the one of Asiyah, and is full of mitzvot only due to Adam’s sin and the corruption of mankind. In Olam HaBa, the Torah of Atzilut will finally be revealed, which is why Jewish tradition holds that many mitzvot will no longer apply in that future time. This is said to be the meaning of Isaiah 51:4 where God proclaims that in the messianic times “a Torah will go forth from Me”; and of Jeremiah 31:30 where God says He will forge a brit chadashah, a “new covenant”, with Israel. (This latter term was usurped by Christians for their “New Testament”.)

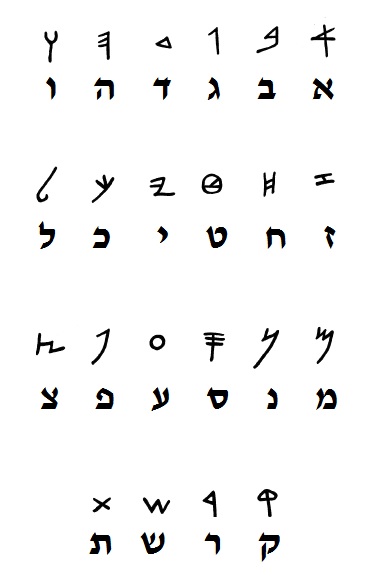

An even more intriguing idea is that the “New Torah” will be composed of the exact same letters as the current one we possess, just rearranged to form new words! Yet another is based on the well-known principle that the Heavenly Torah is composed of “black fire on white fire”. This is often used to explain the fact that the Torah actually has 304,805 letters, even though it is always described as having 600,000 letters (one for each Israelite at Mt. Sinai)—there are 304,805 letters of “black fire” and the rest are the invisible letters of “white fire”. Gershom Scholem cites a number of Kabbalistic and Hasidic texts suggesting that these currently-invisible “white fire” letters are the true eternal Torah! (See Scholem’s Kabbalah, pgs. 171-174, for a complete analysis of these concepts.)

It is this primordial Torah that was originally taught to Adam, and was passed down through his descendants to the Patriarchs, who carefully observed it. As such, it appears that eating matzah is an eternal mitzvah that already appeared in the primordial Torah before the Exodus and the revelation of the current Torah of Asiyah. What was the meaning behind that consumption of matzah?

Bread of Faith

Matzah is called the “bread of faith”. It symbolizes our faithfulness to God, who took us out of Egypt to be His people: “Let My people go so that they may serve Me” (Exodus 7:16, 26). Further emphasizing this point, the word matzot is spelled exactly like mitzvot. This simple, “humble” bread symbolizes our subservience to God’s commands. We are His faithful servants, just as the Patriarchs were His faithful servants. So they, too, ate matzah as a sign of their faith. They ate matzah because God had liberated them, too, from various hardships.

The very first Patriarch, Abraham, was miraculously saved from Nimrod’s furnace. He also dwelled in Egypt for a time before God miraculously brought him out of there with great wealth, just as his descendants would do centuries later. And then came his greatest test of faith: the Akedah. Amazingly, the apocryphal Book of Jubilees connects this event with the future Passover holiday. In chapter 18, it suggests that God commanded the Akedah to Abraham on the 15th of Nisan. As the Torah states, Abraham journeyed for three days before the Akedah happened and then, naturally, it took him three days to return home. Thus, the whole ordeal spanned seven days, and when Abraham returned, he established a seven-day “festival to Hashem” from the 15th of Nisan. The future seven-day Passover holiday would happen on those same days in that same month.

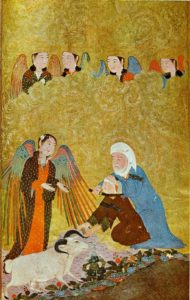

“Abraham’s Sacrifice”, a 15th century piece of Timurid-Mongolian art

While the Sages do debate whether some of the Torah’s major events (including Creation itself) happened in the month of Tishrei or Nisan, the accepted Jewish tradition is that the Akedah happened in Tishrei. Nonetheless, it is quite fitting that the Binding of Isaac should happen on Passover, when Isaac was born. In this case, the ram that Abraham ultimately offered in place of Isaac would serve as a proto-Pesach offering. After all, the ram is nothing but a male sheep, and it is the ram that is the astrological sign of Nisan, and it was those ram-headed gods that the Egyptians worshipped that needed to be slaughtered by the Israelites (as discussed last week). Whatever the case, the Book of Jubilees offers an intriguing possibility for the spiritual origins of Passover, and for why the Patriarchs themselves ate matzot long before the Exodus.

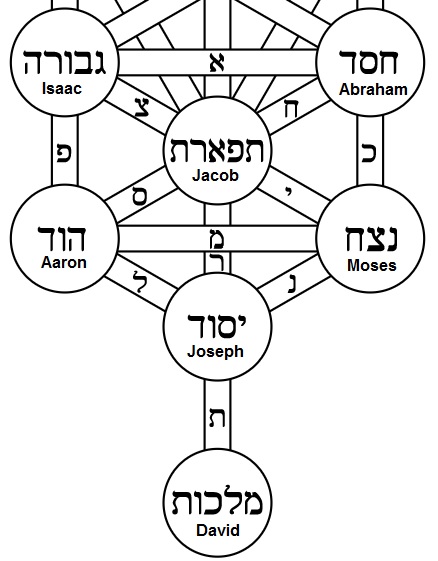

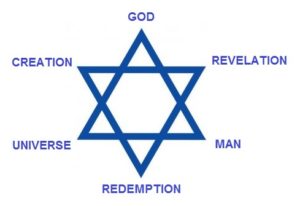

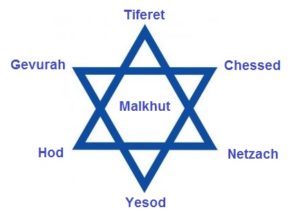

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.

This arrangement of seven (or more specifically, of three-three-one) is found within the Menorah, too, that most ancient of Jewish symbols. For this reason, some argue that the opinion of the Shield of David having the Menorah and the opinion of it having the hexagram are really one and the same. They both reflect a divine geometry of 3-3-1. The sefirot are arranged in the same 3-3-1 manner, and corresponding to them are the seven shepherds of Israel: Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet parallel the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Netzach, Hod, Yesod parallel the next three great leaders of Moses, Aaron, and Joseph; and Malkhut (“Kingdom”) naturally stands for David. David is at the centre of the star, so it is fitting that the star is named after him.