The most recognizable symbol of Lag b’Omer is undoubtedly the bonfire. What is the meaning behind it? The simplest and most-oft heard answer is to commemorate the passing of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and the fiery description of his last moments in the Idra Zuta, his concluding mystical discourse, as recorded in the Zohar (on parashat Ha’azinu). The last verse that Rashbi cited was Psalm 133:3 (note the 33s!) which states that Zion is the place where “God commanded blessing, everlasting life.” As he recited the word “life”, chaim, his last breath left him and his soul ascended Heavenward.

The most recognizable symbol of Lag b’Omer is undoubtedly the bonfire. What is the meaning behind it? The simplest and most-oft heard answer is to commemorate the passing of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and the fiery description of his last moments in the Idra Zuta, his concluding mystical discourse, as recorded in the Zohar (on parashat Ha’azinu). The last verse that Rashbi cited was Psalm 133:3 (note the 33s!) which states that Zion is the place where “God commanded blessing, everlasting life.” As he recited the word “life”, chaim, his last breath left him and his soul ascended Heavenward.

Such was the testimony of Rashbi’s scribe, Rabbi Abba, who writes how he frantically took notes as Rashbi spoke (these writings would later form the core of the Zohar). Rabbi Abba couldn’t look at Rashbi for his light was blindingly strong. After Rashbi passed on, “the fire did not cease from the house and no one reached him for they could not because of the light and fire that encircled him.” When the fires finally subsided, the students saw Rashbi “lying on his right side with a smiling face.” They prepared a bed for him and carried him out towards the caves outside Meron. The villagers of nearby Tzippori (Sepphoris) rushed after them wishing to have his holy body buried in Tzippori. The bed rose into the air and blazed with fire. Rabbi Abba and Rashbi’s son Rabbi Elazar ultimately brought the bed to the cave in Meron, and heard a Heavenly voice resonate: “This is the man who caused the earth to tremble…”

Since it is believed that Lag b’Omer is the day Rashi passed away and this fiery event took place, it is customary to light bonfires and gather around them to share words of Torah. Having said that, there aren’t actually any ancient sources suggesting that Rashbi passed away on Lag b’Omer. Some say it is instead the day when Rabbi Akiva began to teach Rashbi, or when Rashbi and his son left the cave after 13 years in hiding and study, or when Rashbi first started to reveal the Torah’s deepest secrets. What we know is that it is the day the students of Rabbi Akiva ceased dying, and Rashbi was one of the few survivors who went on to revive Judaism. The almighty Roman Empire was unable to extinguish the Jewish flame, which continues to burn brightly today.

Historical reasons and customs aside, there is tremendous spiritual meaning to fire. Let’s uncover a little bit of that mystery.

Three Mystical Substances

One of the most ancient mystical texts is Hilkhot HaKise, “Laws of the Throne”, dating back to the time of Rashbi himself. This short work is almost entirely unknown today. It can be found in a compilation of ancient texts called Merkavah Shlemah, the “Complete Chariot”, compiled by one of my ancestors, Rabbi Shlomo Moussaieff, who was a collector of antiques and precious manuscripts. In Hilkhot HaKise, we read how God has a set of 73 names that are related to Creation. This number is the gematria of chokhmah (חכמה), “wisdom”, with which God created the cosmos. God then took three of these names and from them formed the primordial elements of fire, water, and light—the most mysterious of substances.

Amazingly, as scientifically advanced as we are today, we are still quite clueless about the nature of fire, water, and light! Quantum physicists have spent much time studying light, and are still baffled by its wave-particle duality, its unfathomable speed, and its ability to defy time (it seems that time literally stops at the speed of light!) Chemists are still puzzled by the incredible properties of water, which simply do not fit into the natural pattern. I think it was best described by renowned scientist Oliver Sacks in his book about his “chemical boyhood”, Uncle Tungsten, where he wrote:

…the hydrides of sulfur (H2S), selenium (H2Se), and tellurium (H2Te), all Group VI elements, all dangerous and vile-smelling gases. The hydride of oxygen, the first Group VI element, one might predict by analogy, would be a foul-smelling, poisonous, inflammable gas, too, condensing to a nasty liquid around -100℃. And instead it was water, H2O – stable, potable, odorless, benign, and with a host of special, indeed unique properties (its expansion when frozen, its great heat capacity, its capacity as an ionizing solvent, etc.) which made it indispensable to our watery planet, indispensable to life itself…

Based on the natural laws of the universe, water should be a poisonous and foul gas like the other compounds in its group, yet instead it is a potable, life-giving liquid. It’s special molecular shape and teeny-tiny size, coupled with unusually strong intermolecular forces, make water unlike anything else in existence. And that’s not to mention its controversial (some might say pseudo-scientific) ability to hold information and store “memories” (a notion that even made its way into the Frozen 2 children’s film). Like light, water is an absolute mystery. (For more, see: ‘Shehakol: the Mystical Chemistry of Water’.) And like light and water, fire is also a puzzle.

Six Types of Fire

What is fire? It is hot, and the result of a combustion reaction—we know that much. But what is it exactly? It seems to be gaseous, yet typically contains solid soot particles within, too, all while the flame itself cannot actually be “grasped” or contained like regular matter. It can come in many mesmerizing colours, is affected by gravity, and is able to emit a wide variety of radiation besides visible light, including infrared and UV. It is an energy of some sort, but very difficult to accurately describe or define. Our Sages spoke of six types of fire (Yoma 21b):

There is fire (1) that “eats” but does not “drink”; and (2) there is fire that “drinks” but does not “eat”; and (3) there is fire that “eats” and “drinks”; and (4) there is fire that consumes wet objects like dry objects; and (5) there is fire that repels fire; and (6) there is fire that consumes fire.

Fire that “eats” but does not “drink”—this is regular fire. Fire that “drinks” but does not “eat”—this is [the fever] of the sick. Fire that “eats” and “drinks” is the fire of Eliyahu, as it is written: “…and it licked up the water that was in the trench.” [I Kings 18:38] Fire that consumes wet objects like dry objects is the fire of the wooden pyre [in the Temple]. Fire that repels fire is that of [the angel] Gabriel. Fire that consumes fire is that of the Shekhinah, as the Master said: “He extended His finger and burned them…”

The first type of fire is regular fire which burns solids but does not burn water. The second type consumes water, too, and this refers to a bodily fever. The fever dehydrates the body and “consumes” its water, but does not consume the body itself. While a simple reading might seem like a fever is not a literal fire but only a metaphorical one, the truth is that the human body produces energy through cellular respiration, which actually has essentially the exact same chemical equation as regular combustion! Just as a flame needs oxygen to be sustained, the human body breathes in oxygen to keep the mitochondria in our cells producing energy. On a chemical level, both cellular respiration and combustion are simply oxidation reactions, with oxygen serving as an “electron acceptor”.

The fire of Eliyahu refers to the famous incident at Mount Carmel when Eliyahu miraculously drew down a flame from Heaven that burned through a soaking-wet pyre. The fourth type of fire is the miraculous fire of the Holy Temple, where both dry and moist wood would easily burn on the pyre. The fire of Gabriel refers to the incident in the Book of Daniel when Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah were miraculously rescued from the fiery furnace. Gabriel is one of the Seraphim, literally the “burning” angels. His fire was able to push off the physical fire to save the Jewish captives.

The last type of flame is that of the Shekhinah. The Talmud is referring to another place (Sanhedrin 38b) where God is described as burning away His fiery angels at will. This is the loftiest and most powerful type of fire. Just as an earthly fire can purify metals and other substances, the divine flame can purify souls and angels. This is the fire of Gehinnom, too, which is not a place of eternal damnation, but rather a purgatory to rectify contaminated souls. It ties into a statement of our Sages that “fire is one-sixtieth of Gehinnom” (Berakhot 57b), and also helps to explain the statement that Torah scholars are entirely immune to the fires of Gehinnom (Chagigah 27a). Since God’s Word is fire (as stated in Jeremiah 23:29), those who study it intensely become encased in a fiery shield. Finally, the connection between fire and Gehinnom is suggested again in the same passage of Hilkhot haKise cited above:

After creating the primordial mystical elements of fire, water, and light out of His own holy names, God further made three things from each. He took three “drops” of primordial fire and created His divine Throne, the angels, and Gehinnom. He then took three “drops” of water and created the Heavens, the clouds and moisture of the atmosphere, and the oceans and hydrosphere (for lots more on the Heavens being composed of water, see Secrets of the Last Waters). Lastly, He took three “drops” of light and hid one away as the Or HaGanuz for the righteous in the World to Come, another was hidden away for the future restored light of the moon (which currently only reflects sunlight), and the last drop is for the physical light of this cosmos.

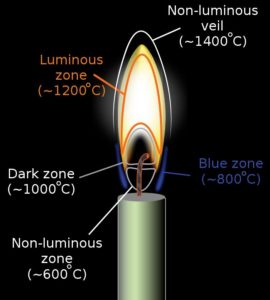

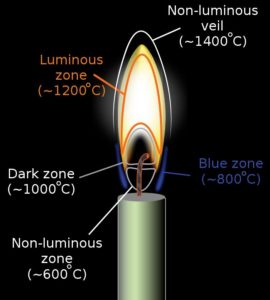

Three Colours of a Flame

The Zohar (III, 33a, Ra’aya Mehemna—note the 33s again!) explains the meaning of the three colours within a flame. A typical flame will mainly have white (or yellow) light, with a black region at its base, around which is a blue flame. The white, black, and blue correspond to the three parts of Scripture: Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim; as well as to the three parts of the Jewish people: Kohen, Levi, and Israel. The Zohar says that the most special flame is the blue flame, which is tekhelet, and represents the Shekhinah. Scientifically, the blue flame is a “complete” flame, meaning it receives plenty of oxygen, whereas a yellow flame is “incomplete” and lacking oxygen. In another place (I, 83b) the Zohar says the three colours of the flame correspond to the three major levels of the soul: the black flame nearest the wick is the lowly nefesh; the white light above is the ruach; and the thin sliver of blue—the most “concealed” of the lights—is the great neshamah. This helps us better understand the verse in Mishlei that “the candle of God is the soul of man” (Proverbs 20:27).

The Zohar (III, 33a, Ra’aya Mehemna—note the 33s again!) explains the meaning of the three colours within a flame. A typical flame will mainly have white (or yellow) light, with a black region at its base, around which is a blue flame. The white, black, and blue correspond to the three parts of Scripture: Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim; as well as to the three parts of the Jewish people: Kohen, Levi, and Israel. The Zohar says that the most special flame is the blue flame, which is tekhelet, and represents the Shekhinah. Scientifically, the blue flame is a “complete” flame, meaning it receives plenty of oxygen, whereas a yellow flame is “incomplete” and lacking oxygen. In another place (I, 83b) the Zohar says the three colours of the flame correspond to the three major levels of the soul: the black flame nearest the wick is the lowly nefesh; the white light above is the ruach; and the thin sliver of blue—the most “concealed” of the lights—is the great neshamah. This helps us better understand the verse in Mishlei that “the candle of God is the soul of man” (Proverbs 20:27).

We can further parallel these three flame colours to the three “drops” of fire mentioned in Hilkhot haKise above. The first drop which was used to make the Throne is the blue flame representing the Shekhinah. Multiple other sources speak of God’s Throne as being of a sapphire blue colour. The white flame alludes to the white glow of the angels, who were fashioned from the second drop; while the black flame alludes to the darkness of Gehinnom.

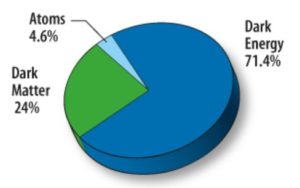

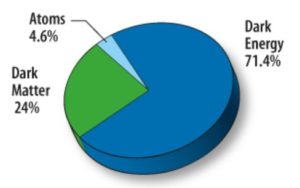

Composition of the Universe (Courtesy: NASA)

Elsewhere, the Zohar (I, 16a) speaks of four types of mystical fire that are black, red, green, and white. One might quickly notice that these correspond to the traditional four humours of the human body (black humour being the “melancholy” of the kidneys and spleen, red being blood, green being bile, and white being phlegm). This passage in the Zohar is commenting on the process of Creation and is deeply esoteric. It is describing grander cosmic entities with fiery metaphors. For instance, it states that the “black fire” is the most powerful in the universe, and it is the “darkness” (חֹשֶׁךְ) mentioned in Genesis 1:2. It is an invisible dark force that permeates the entire cosmos. This may very well be a reference to dark energy, a mysterious substance that scientists have yet to understand, but is estimated to make up some 70% of our universe!

These are just some of the profound mysteries within the realm of fire, and things to ponder while you gaze at your Lag b’Omer bonfire. Chag sameach!

Make your Shavuot all-night learning meaningful with

Tikkun Leil Shavuot – The Arizal’s Torah Study Guide