This week’s parasha, Vayikra, begins outlining all the sacrificial services in the Tabernacle (and future Temple). One category of offerings is called shelamim, “peace offerings”, introduced at the start of chapter 3. Our Sages taught (as cited by commentators like Rashi and Bartenura) that these offerings are called “peace offerings” because they serve to infuse the entire world with peace. The Zohar (III, 9b) picks up on this and opens a discourse on the nature of the “entire world”, and what it is really composed of. The Zohar states that when God created the world, He created “seven heavens above, seven earths [or lands] below, seven seas, seven [great] rivers, seven days, seven weeks, seven years [in a cycle] seven times, and seven thousand years [of civilization] that the world will endure…”

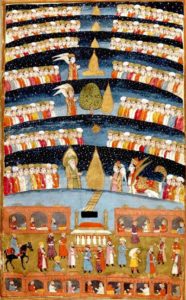

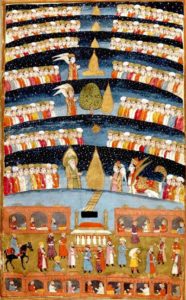

An 1808 Persian illustration of the Seven Heavens

The Zohar here draws from a more ancient Midrash that “all sevens are beloved” (Vayikra Rabbah 29:11). That Midrash expounds on another place in Vayikra that outlines the High Holidays, which are specifically in the seventh month of the year. Why the seventh? The Midrash states that there are seven heavens, and the highest heaven, called Aravot (from Psalms 68:5), is the most beloved. Of the seven earths or lands, the highest is called Tevel (as in Psalms 9:9), which we humans inhabit, and it is most beloved. The seventh generation from Adam was most beloved, for this was the generation of Enoch, who “walked” with God and never died, transforming into an angel. Similarly, the seventh generation of God’s chosen people was most beloved, for Moses was the seventh generation starting from Abraham. The Midrash continues with other sevens, including that the seventh day (Shabbat) is most beloved, as is the seventh Sabbatical year (Shemitah), and the seventh month, Tishrei, which is why the High Holidays are in that month.

Now, the Midrash above seems to suggest that just as the seven heavens are overlayed one on top of another, so too are the seven “earths” overlayed one of top of another. The surface world is our Tevel, and beneath us are six more layers of worlds, respectively called Eretz, Adamah, Arka, Gai, Tziyah, and Neshiya (אֶרֶץ, אֲדָמָה, אַרְקָא, גַּיְא, צִיָה, נְשִׁיָּה). The Zohar first quotes this teaching, tracing it back to Adam himself, and says that the lower worlds are arranged concentrically like an onion. In each subterranean world are distinct creatures that are different than those in our world. However, the Zohar then brings an alternate teaching from the great Rav Hamnuna Saba. This one is absolutely breathtaking because of its precise scientific knowledge, way ahead of its time:

… the entire world spins around like a ball, with some [people] on top and some [people] below. The living beings [across the seven lands] all differ in their appearance because of the different environments in each land, yet are all like other human beings.

When one land has light, another land has darkness, so that when it is daytime for one group [of people], it is nighttime for the other. In one land, it is always daytime, except for a short hour of night. And this is the [true meaning] of what is written in the ancient Book of Adam.

The Zohar here addresses all of our concerns and makes sense of the seven lands. The truth is that the seven lands are all on the surface, just different continents around our globe. The beings in these worlds are not distinct, bizarre creatures, but just like all shar bnei nasha, other normal human beings, but with different skin colours and appearances since they adapt to their environment!

Not only does the Zohar reveal that there are seven continents (something that humans would not uncover for hundreds of more years!) but it also tells us the world is spherical, and that it is rotating “like a ball” (not confirmed by scientists until the 1800s!) The Zohar knows about time zones, too, and says that it is daytime in some continents while it is simultaneously night in other continents. More incredible still, it knows that in the continent of Antarctica (first sighted only in 1820!) it is sometimes entirely day with practically no night, and vice versa. (This is true in the Arctic as well, but the Arctic is not a continent.)

Rav Hamnuna Saba concludes that this is the true meaning of the ancient secret of the seven lands. One should not think that the worlds are subterranean and arranged like an onion, for this is an incorrect interpretation. To help confirm this, the Zohar goes on to relay a story about Rav Nehorai Saba, who rejected the Midrash about the seven lands and did not believe it could be true. It happened that he was once at sea and a terrible storm began to rage. The ship capsized and Rav Nehorai was cast into the depths of the ocean. He washed up on a foreign land, with strange-looking people speaking a language he did not understand. Eventually, a miracle happened and he was teleported back to his home. He would often be found crying in the study halls, and when people asked why, he answered: “Because I sinned against belief in the words of the Sages…” Rav Nehorai would henceforth teach: “Happy are the righteous who labour in the Torah and know the mysteries of the supernal secrets; woe to those who disagree with them and are not believers!”

Rav Nehorai was not alone in his initial doubt. Even the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) living in the 16th century still had a hard time believing in the seven lands, and admitted that it seemed impossible and baffling! He concluded that, like Rav Nehorai, one should accept it on faith alone (see Pardes Rimonim, Gate 6, Chapter 3). Today, we don’t have to be baffled, and we have all the empirical evidence we need to know that Rav Hamnuna Saba was correct all along. Science has finally caught up and confirmed what was once a most profound mystical secret.

Cain’s Children

Elsewhere (I, 9b), the Zohar states that when God banished Cain following his murder of Abel, he was exiled to the land of Arka, one of the “seven lands”. While some erroneously thought this to mean that Cain was somehow sent deep into the nether regions of the planet, the truth is that, as we’ve seen, he was simply banished to another continent. We learn that Cain mated with the people there, and this is where his children came from. This confirms the statement of Rav Hamnuna Saba that the inhabitants of the other lands are human beings, too, and not strange otherworldly creatures. Cain just went to another continent, probably Africa or Asia. (The Torah says in Genesis 4:16 that Cain went to the region of Nod, east of Eden.)

The Zohar above solves another great mystery: if Adam and Eve were the only people, and they only had Cain and Abel, the latter of which died, who could Cain have mated with? The Zohar reveals that there were other, “uncivilized” people, too. Adam and Eve were unique in that they were given a divine intellect, but they were not alone. This also explains why the Torah seemingly mentions the creation of man twice, in both chapters 1 and 2 of Genesis. The inescapable conclusion is that chapter 1 of Genesis describes the creation of mankind, all human beings, while chapter 2, in the Garden of Eden, describes the birth of the first fully civilized man, infused with a unique divine spirit, and given the tools to transform the world. Cain would have been the first to set forth and “civilize” the rest of the world. This may be why the Torah specifically tells us that Cain went and built a city (Genesis 4:17).

In any case, Cain’s descendants all perished in the Great Flood, leaving only the line of Seth, from whom Noah and his children descended. Intriguingly, Rav Yonatan Eybeschutz (1690-1764), in his Tiferet Yonatan commentary on the Torah, held that the Great Flood did not affect the Americas! Only the Old World of Asia, Africa, and Europe were punished. His reasoning is pretty solid: Had the Flood destroyed everyone around the globe, how could Noah’s children have populated the New World? They didn’t have the advanced ships needed to traverse the oceans! We must conclude that America was spared, and the people there, who were not affected by the sins of the Old World anyway, were completely unharmed. (We probably have to include Australia here, too.)

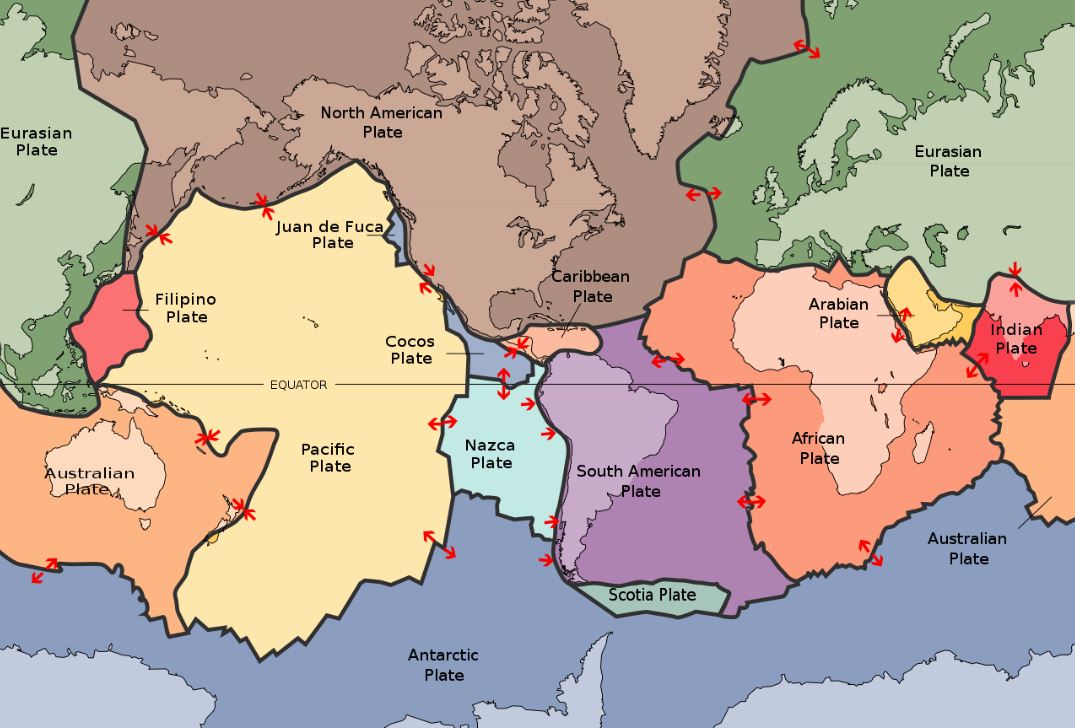

On this note, it is important to mention that some in the religious world think that the continents only split as a result of the Great Flood. Both Torah and science agree that the continents were once joined together (a landmass scientists refer to as Pangea). However, scientists estimate that the continents split long ago, and it could not have happened within the timeframe of human history. Rav Eybeschutz’s statement also confirms that the continents were already split at the time of the Flood. As the Midrash cited above states, God created the world initially with seven lands, so the seven distinct continents surely already existed at the time of Adam’s creation.

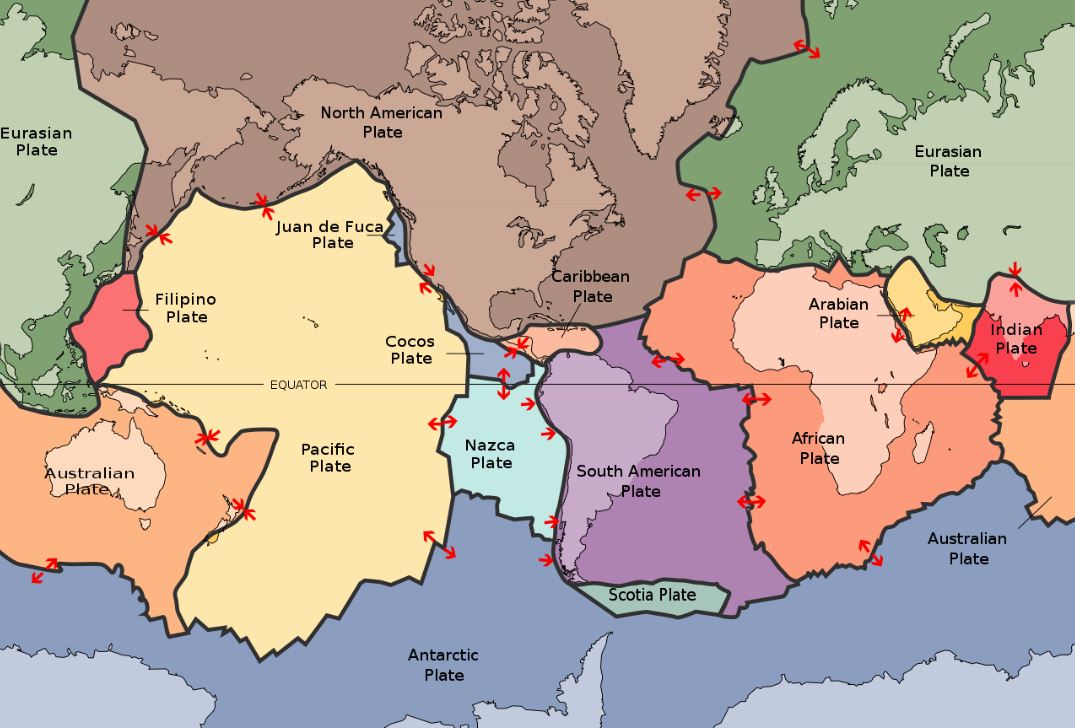

How scientists map the development of the continents, which drift about 2.5 centimetres per year. For how to deal with the age of the universe and reconciling it with Torah chronology, see here.

Continental Sefirot

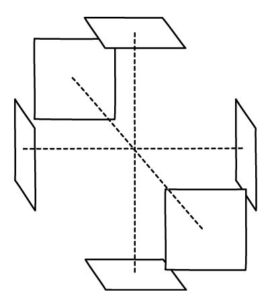

The three upper Sefirot of mochin (in blue) and the seven lower Sefirot of the middot (in red).

When the Zohar speaks of all the sevens embedded in Creation, it implies that these correspond to the seven lower Sefirot. So, how do we connect the continents to the Sefirot? The Old World three of Asia, Africa, and Europe are surely tied to the three main axes of Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet. We generally say that Noah’s sons divided up the three Old continents amongst themselves, with Shem getting Asia, Ham getting Africa, and Yefet getting Europe. The Zohar (I, 73a) tells us that the three sons embody Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet, so we can easily conclude that Asia is Chessed, Africa is Gevurah, and Europe is Tiferet.

Asia is by far the largest continent, and Chessed is also called Gedulah, “largeness”. Asian cultures are known for their warm hospitality and their altruistic, tight-knit communities, a sure sign of Chessed. There is no doubt that hot Africa, with its difficult history, is the severity of fiery Gevurah, also called Din, harsh “judgement”. Tiferet is “beauty”, sharing a close root with Yefet, which means pretty much the same thing.

It is worth briefly exploring the unique case of the land of Israel. Geographically, we consider Israel to be a part of Asia, and those Asian qualities mentioned above are certainly prominent in the Holy Land. Yet, mystical texts typically associate Israel with Tiferet, which is closer to Europe. Indeed, Israel’s history is most closely intertwined with that of Europe, and not only in the present day when Israel is politically closer to Europe than Asia, but even in ancient times during its close encounters with Greece and Rome. Geologically, meanwhile, the land of Israel is actually part of the African continental plate! (This makes a lot of sense, too, since Canaan was a son of Ham, who got Africa.) We have to conclude that Israel, being a special land, is really outside of the seven divisions, and has elements of all the continents and all the Sefirot. (It’s important to note here that the continental plates don’t match up exactly with our divisions of the continents, since Europe and Asia are part of one Eurasian plate, while India and Arabia have their own tectonic plates.)

The “twin” continents of North and South America are undoubtedly the “twin” Sefirot of Netzach and Hod. This explains well the qualities of both: North America is the place that contains history’s most dominant and powerful empire—a fitting aspect of “victorious” Netzach. South America, meanwhile, is best known for its vibrant cultures and colours, and its showmanship in music, dance, and sports—a clear aspect of the “splendorous” Hod.

Australia is best paired with Yesod. An interesting parallel here can be made when we remember that the personification of Yesod was Joseph. He was a prisoner sent “down under” unjustly, but nonetheless emerged from this ordeal into greatness. Australia, too, is infamous for its origins as a penal colony, where the British originally sent their prisoners. (Australia celebrates its national holiday, Australia Day, on January 26th, the anniversary of the day that the penal colony was established in 1788!)

Finally, there is no doubt about the nature of cold and empty Antarctica at the very bottom of the globe. This is the “empty” Malkhut at the bottom of the Sefirot, with little energy of its own to emit and serving only as the receptable for the Sefirot above. We might learn from this that, while Antarctica has seemingly played no role in human history thus far, it has a significant role to play in the future era of Malkhut, when God’s Kingship will be revealed once again—an era which we all hope and pray will be upon us imminently.

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.