This week we conclude the fourth book of the Torah with a reading of the last two portions. In parashat Masei, “Journeys”, we are given a summary of the Israelites’ travels in the Wilderness. There are a total of forty-two trips and stops along the way. The Baal Shem Tov famously taught that these 42 journeys actually allude to the 42 journeys of every soul. His grandson wrote in Degel Machane Ephraim that “one’s birth and emergence from the mother’s womb is like the Exodus, as is known, and one henceforth goes from journey to journey until arriving at the supernal world…” The journey begins here on Earth with a person emerging from the waters of the womb, much like the Israelites emerged out of the waters of the Red Sea. It continues until the soul returns to its place in the supernal worlds. What do these supernal worlds look like and how long do journeys through those worlds take?

The Talmud outlines the supernal worlds, and states that the distance between each one is a “five hundred-year’s journey” (Chagigah 12b-13a). The first of the “Seven Heavens” is called Vilon, literally a “curtain”. The Talmud describes this simply as the atmosphere above Earth’s surface, and it has no particular spiritual significance. Then comes the Rakia, often poorly translated as “firmament”. The Talmud repeats what the Torah says in the account of Creation that within the Rakia are the sun, moon, stars, and constellations. In other words, Rakia is outer space. When the Sages used the term “fixed” (kevu’in) it does not mean that the stars are “fixed” into a solid firmament, but rather that the stars are all “fixed” in their orbits. (The same word is used when telling us to “fix” specific cyclical times for Torah study.)

AI-generated image of Seven Heavens

The third level is Shechakim, the “millstones” that grind manna. This region can be thought of as the interface between the “physical” world and the “spiritual” world. Indeed, when Rabbi Akiva led three other rabbis into the spiritual worlds of Pardes (recounted in the following pages in the same tractate Chagigah), he tells the others that they will pass by “pure marble stones” along the way. It is appropriate that manna would come from here specifically, as manna was a substance part physical and part spiritual, a blend of both dimensions.

The fourth Heaven is called Zevul, and this is where the “Heavenly Jerusalem” is found. The kohen gadol in its Temple is the angel Michael, who brings offerings upon the Heavenly altar. Most of the other angels dwell above in the fifth Heaven called Ma’on. The next Heaven is called Machon, the realm of the primordial elements. Apparently, here is found snow, hail, dew, rain, and fire, together with storms and whirlwinds. The Talmud then asks what any of us would ask: aren’t these elements here on Earth? The conclusion is that their original (spiritual) source is up in Machon. One might understand this place as God’s own “laboratory”, where He set forth the very foundations of the cosmos. This can be likened to the mystical dimension of Beriah, which serves as the “programming” and “back-end” for the universe. Similarly, the first two lower Heavens of Vilon and Rakia—typically described in very physical and mundane terms—would parallel the lowest realm of Asiyah, while the angelic Ma’on would parallel Yetzirah (perhaps Shechakim is in between, or bridges both).

Finally, the Seventh Heaven is called ‘Aravot. This is the place of souls and spirits, the source of all blessings, as well as the Dew of Resurrection that will revive the dead in the World to Come. Here are the highest classes of angels like Ofanim and Seraphim. And here, too, is the Throne of God. This region parallels the dimension of Atzilut. The Talmud then says there is one more Rakia above, an “eighth” Heaven, but it is so mysterious and sublime it is forbidden to speak of it at all. The source for it is Ezekiel 1:22, which speaks of a Rakia of “terrible ice”. This takes us right back to the beginning of the passage, where there is one opinion stating there are actually two types of Rakia, a lower and higher one (based on Deuteronomy 10:14). This neatly corresponds to the mysterious and highest mystical dimension of Adam Kadmon.

The Deuteronomy verse above mentions both hashamayim and shmei hashamayim, hence the implication of two distinct Rakias. Based on the word hashamayim (השמים), the numerical value of which is 955 (when counting with the mem sofit as 600), it is said that the Heavens are further divided up into 955 levels or compartments. The verse starts with the word hen (הן), “behold”, which has a value of 55, from which is derived that the top 55 levels are reserved for God alone, while the bottom 900 are accessible to souls, spirits, angels, and the like.

The Deuteronomy verse above mentions both hashamayim and shmei hashamayim, hence the implication of two distinct Rakias. Based on the word hashamayim (השמים), the numerical value of which is 955 (when counting with the mem sofit as 600), it is said that the Heavens are further divided up into 955 levels or compartments. The verse starts with the word hen (הן), “behold”, which has a value of 55, from which is derived that the top 55 levels are reserved for God alone, while the bottom 900 are accessible to souls, spirits, angels, and the like.

How Big is the Cosmos?

The Talmud (Chagigah 13a) states that the distance from Earth to the Rakia is a “five hundred-years’ journey”, that the Rakia itself is five hundred years-long, and that the distance between each level of Heaven thereafter is five hundred years. (The Talmud rightly excludes the atmospheric Vilon, which we know scientifically doesn’t extend so far away from Earth’s surface). So, with seven domains (including the upper eighth Rakia, but excluding the Vilon), each five hundred years large, and six spaces between them of five hundred years, that gives us a total size to the cosmos of about 6500 “years”. These are not light years, of course, so how big is the cosmos according to the Talmud?

In Talmudic parlance, a day’s journey (derekh yom) is equivalent to ten parsa, or parasangs. A parsa is four mil, and a mil is two thousand amot, or cubits. In other words, a parsa is 8000 cubits. There are varying definitions to the length of a cubit, the common answer being two feet. In that case, we are looking at 16,000 feet per parsa, or just about five kilometres. However, the Talmud (Pesachim 94a) states that the circumference of the Earth is 6000 parsas, and we know today that the Earth’s circumference is 40,075 kilometres. That would mean a parsa is about 6.68 kilometres, which actually makes more sense because the Sages define a parsa as the distance a person walks in 72 minutes (typical walking speed is about five to six kilometres an hour.) Putting it all together, a derekh yom would be about 67 kilometres, the maximum distance a person could cover if they walked an entire day at average speed.

We can take that number and convert it to “five hundred years” as follows: 67 kilometres per day x 365 days x 500 years = 12,227,500 kilometres. This would be the size of each Heaven, as well as the distance between each Heaven. At first glance, that works out to a total of about 159 million kilometres for the size of the cosmos around Earth, according to the Talmud. Intriguingly, this is roughly the same as a scientific Astronomical Unit (AU), which is about 150 million kilometres, based on the average distance between the Earth and the Sun.

However, the Talmud then goes on to state that each aspect of the angels and the Throne of God is so vast it is equivalent in distance to all of the Seven Heavens combined! The Talmud lists eleven items, so doing the math (159 million x 11) brings one to a cosmos nearly 1.8 billion kilometres wide. As mind-boggling as that is, it is still significantly less than the scientific estimate for the size of the Solar System at 287 billion kilometres. Meanwhile, the whole universe is estimated to be at least 93 billion light years wide (a light year is about 9.5 trillion kilometres).

Perhaps the Sages did not mean that the distances are exactly a five hundred-years’ journey (and maybe not a walking journey), but just that the distances are so vast they are impossible for a human to traverse in one lifetime. Indeed, the Talmud here brings up the case of Nimrod, who sought to build the Tower of Babel to ascend to the Heavens. He was told that a human lifespan is only about 70 years, so how could he even think of attempting to travel to the highest Heavens when there are multiple distances of 500 years’ length?

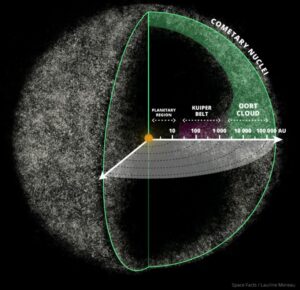

It is interesting to point out that today we know the edge of our Solar System appears to be a “bubble” of ice comets referred to as the Oort Cloud. This region may be related to the “millstones” (or “pure marble stones”) of the third Heaven, Shechakim, or perhaps the “terrible ice” of the mysterious eighth Heaven, the upper Rakia. Whatever the case, both Talmud and science describe vast distances that would be impossible for humans to journey through (at least with current technology). Angels, on the other hand, can traverse such distances. For example, the Talmud recounts Eliyahu once traveling four hundred parsas in one instant to save Rav Kahanah (Kiddushin 40a), while the Zohar (I, 4b-5a) describes Samael as traveling 6000 parsas in one instant. The angelic Merkavah “chariots” are said to regularly journey through 18,000 worlds (Avodah Zarah 3b; Zohar I, 24a; and based on Chagigah 12b, one can understand all of these 18,000 worlds as being within ‘Aravot, the seventh Heaven).

It is interesting to point out that today we know the edge of our Solar System appears to be a “bubble” of ice comets referred to as the Oort Cloud. This region may be related to the “millstones” (or “pure marble stones”) of the third Heaven, Shechakim, or perhaps the “terrible ice” of the mysterious eighth Heaven, the upper Rakia. Whatever the case, both Talmud and science describe vast distances that would be impossible for humans to journey through (at least with current technology). Angels, on the other hand, can traverse such distances. For example, the Talmud recounts Eliyahu once traveling four hundred parsas in one instant to save Rav Kahanah (Kiddushin 40a), while the Zohar (I, 4b-5a) describes Samael as traveling 6000 parsas in one instant. The angelic Merkavah “chariots” are said to regularly journey through 18,000 worlds (Avodah Zarah 3b; Zohar I, 24a; and based on Chagigah 12b, one can understand all of these 18,000 worlds as being within ‘Aravot, the seventh Heaven).

Then there’s Enoch, who went to “walk with God” (Genesis 5:24) and journeyed through the Heavenly worlds, as described in the apocryphal Book of Enoch and referenced many times throughout the Zohar. And we can’t forget the sages led by Rabbi Akiva who went up to Pardes, with Rabbi Akiva reminding them that they will pass through the “pure marble stones” (of the third Heaven), after which they saw various Heavenly beings and angels (most notably Metatron, identified as that selfsame Enoch) in the fourth, fifth, and sixth Heavens. Finally, in the World to Come, each righteous person will be able to traverse the cosmos, with a reward of 310 worlds (Uktzin 3:12) or perhaps even 400 worlds (Zohar I, 127b) to explore and delight in.

May we merit to see that day soon!

Lots More Information:

The Four Who Entered Pardes (Video)

Metatron & the Book of Enoch (Video)

Kefitzat HaDerekh: Wormholes in the Torah

For those who liked the essay on ‘The Strings That Hold the World’ from several weeks ago, there is an updated, revised, and expanded version here.

And since it’s that time of year, please review ‘The Right Way to Observe the Three Weeks’ here.

The Deuteronomy verse above mentions both hashamayim and shmei hashamayim, hence the implication of two distinct Rakias. Based on the word hashamayim (השמים), the numerical value of which is 955 (when counting with the mem sofit as 600), it is said that the Heavens are further divided up into 955 levels or compartments. The verse starts with the word hen (הן), “behold”, which has a value of 55, from which is derived that the top 55 levels are reserved for God alone, while the bottom 900 are accessible to souls, spirits, angels, and the like.

The Deuteronomy verse above mentions both hashamayim and shmei hashamayim, hence the implication of two distinct Rakias. Based on the word hashamayim (השמים), the numerical value of which is 955 (when counting with the mem sofit as 600), it is said that the Heavens are further divided up into 955 levels or compartments. The verse starts with the word hen (הן), “behold”, which has a value of 55, from which is derived that the top 55 levels are reserved for God alone, while the bottom 900 are accessible to souls, spirits, angels, and the like.