The Torah states that Israel is the land of the Jewish people. However, God makes clear that only when we are righteous and live by His Word will we merit to dwell in His most special territory. Otherwise, the land itself will “vomit” us out (Leviticus 18:28), as it does all of those who are impure. It is amazing to see how history corroborates this incredible prophecy. For thousands of years, the Holy Land essentially lay desolate, save for small Jewish and non-Jewish communities here and there. No empire was able to hold onto this territory for long, and no foreign kingdom was able to establish itself in any kind of perpetuity or prosperity.

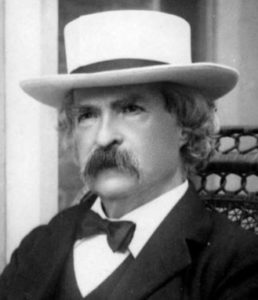

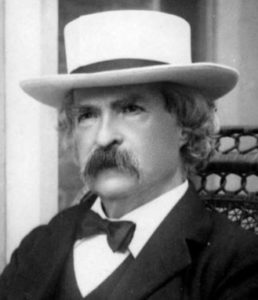

The Babylonians very quickly lost Israel to the Persians, and the Persians soon lost it to the Greeks. The Ptolemys and Seleucids fought over it unsuccessfully for decades until the Maccabees restored a prosperous Jewish kingdom. Their sins and infighting led to the Roman takeover of Israel. But the Romans, too, had an extremely hard time holding onto it. After the Romans destroyed the Second Temple, their fate was sealed as well. Their golden age was behind them, and Rome was henceforth on a steady decline. The Byzantines and Sassanids would fight over Israel back and forth until the Arabs took it. Then the various Arab caliphates fought over it, until the Crusaders decided it should be theirs. The Crusader era was one of indescribable violence and bloodshed, following which the Holy Land remained fallow for centuries. When Mark Twain visited in 1869, he wrote that it is a:

Mark Twain

desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds—a silent mournful expanse… A desolation is here that not even imagination can grace with the pomp of life and action… We never saw a human being on the whole route….There was hardly a tree or a shrub anywhere. Even the olive and the cactus, those fast friends of the worthless soil, had almost deserted the country… Of all the lands there are for dismal scenery, I think Palestine must be the prince… Can the curse of the Deity beautify a land? Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies. (The Innocents Abroad)

On that note, it is important to remember Twain’s account when dealing with Pro-Palestinians who falsely (and quite humorously) claim that Israel was full of Arabs when the Zionists arrived and “displaced” them. The historical reality, confirmed by accounts like Twain’s and other travellers, is that there was hardly “a human being” there. Ironically, the vast majority (though certainly not all) of “Palestinians” only came to settle in Israel when the Zionists arrived and created new prosperity and work opportunities. Occasionally, the Arabs admit this themselves, as did Fathi Hammad, Hamas’ Minister of the Interior, when he passionately spoke in a television address (see here) and said:

Brothers, half of the Palestinians are Egyptians and the other half are Saudis. Who are the Palestinians? Egyptian! They may be from Alexandria, from Cairo, from Dumietta, from the North, from Aswan, from Upper Egypt. We are Egyptians. We are Arabs.

Zuheir Moshan, the commander of the Palestinian Liberation Organization commander from 1971 to 1979, similarly said:

The Palestinian people does not exist. The creation of a Palestine state is only a means for continuing our struggle against the state of Israel for our Arab unity.

History makes it undoubtedly clear: Israel is the land of the Jews, for the Jews. No other nation has ever been successful in Israel except for the Jews. No other nation has ever established any lasting, flourishing presence there except for the Jews. Just as there was a vibrant Jewish kingdom in Israel three thousand years ago in the time of Solomon, there is a vibrant Jewish state there today.

It is important to keep in mind that the Torah clearly states that those who are impure—whether Jews or not—will be expelled from the Holy Land. We can therefore reason that those who do dwell in it securely are permitted to do so by the Land, which is not expelling them, and are its rightful inhabitants. Based on this, the great Rabbi Avraham Azulai (c. 1570-1643) wrote:

And you should know, every person who lives in the Land of Israel is considered a tzadik, including those who do not appear to be tzadikim. For if he was not righteous, the land would expel him, as it says “a land that vomits out its inhabitants.” (Leviticus 18:25) Since the land did not vomit him out, he is certainly righteous, even though he appears to be wicked. (Chessed L’Avraham, Ma’ayan 3, Nahar 12)

In this light, we can understand that even the most secular Zionists—who may appear to be “wicked” and “impure”—are still considered tzadikim in some way. With that lengthy preamble, let us try to understand the Zionist mindset and vision, and explore the true, little-known origins of Zionism.

A Religious Movement

It is commonly believed that Zionism essentially began as a movement of secular Ashkenazis in the late 1800s, with Theodor Herzl (wrongly) credited as the movement’s founder. The surprising reality is very different.

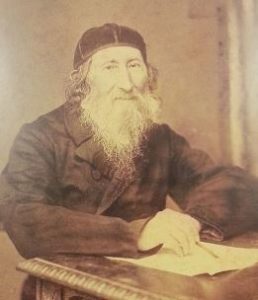

While it is hard to credit any one person with lighting the spark of Zionism, the best candidate is probably Rabbi Yehuda Bibas (1789-1852), the scion of a long line of illustrious Sephardic rabbis. Rabbi Bibas was the head of the renowned Gibralter yeshiva, and later the Chief Rabbi of Corfu, Greece. Throughout his travels across the Mediterranean, both in Southern Europe and North Africa, Rabbi Bibas witnessed constant persecutions of Jews. Regardless of whether Jews tried to fit in with mainstream society or not, or whether they were productive good citizens or not, the anti-Semitism would not abate.

Rabbi Bibas became convinced that the only solution is for Jews to return to their Biblical homeland and rebuild their kingdom. Like Mark Twain a couple of decades after him, Rabbi Bibas recognized that the land of Israel was lying fallow, accursed, devoid of inhabitants, and was ripe for Jewish resettlement. In 1839, he embarked on a world tour to convince Jews to make aliyah, and to gain support for a mass movement of Jewish settlement and nation-building.

Sir Moses Montefiore

Rabbi Bibas’ trip was funded by fellow Sephardic Jew Sir Moses Montefiore (1784-1885), who was born in Livorno, Italy, where Rabbi Bibas had studied in his youth. Montefiore became exceedingly wealthy in England, and later served as the Sheriff of London before being knighted by Queen Victoria. During his first trip to Israel in 1827, Montefiore was deeply touched and resolved to become a fully Torah-observant Jew. He established a Sephardic yeshiva, and built what is now the Montefiore Synagogue in Kent, England. He was known to bring a shochet with him on every trip to ensure he would have kosher meat. (A wealthy anti-Semite once told Montefiore that he had just returned from Japan, where there are “neither pigs nor Jews.” Montefiore replied: “Then you and I should go there, so that they should have a sample of each.”)

Montefiore made a total of seven trips to Israel, and like his friend Rabbi Bibas, was convinced that the Jews must return to their homeland and rebuild their nation-state. In fact, Montefiore laid the groundwork for the later Zionist movement. He paid for the construction of Israel’s first printing press and textile factory, rebuilt a number of synagogues and Jewish holy sites (including Rachel’s Tomb) and established several agricultural colonies. He commissioned censuses of the Holy Land’s population, which are still valuable to historians today (you can scan them here). His 1839 census of Jerusalem, for example, found that more than half of the city’s population were Sephardic Jews (over 3500 people). These statistics show that Jews were already the majority in much of the Holy Land, long before the Zionist movement officially began.

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Kalischer

One of Montefiore’s most vocal Ashkenazi supporters was Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795-1874). Rabbi Kalischer was a student of the renowned Rabbis Akiva Eiger and Yakov Lisser, the Baal HaNetivot. Rabbi Kalischer saw firsthand the struggles that German and Eastern Europe Jews were living through. He was also frustrated by the abject poverty experienced by the Jews living in Israel. At that time, it was common for Jews to collect funds from the diaspora to send to their brothers in Israel. Rabbi Kalischer believed that Israel’s Jews must return to an agricultural life, and learn to cultivate the rich land on their own, so that they could become self-subsisting. He believed that the Jewish masses of Eastern Europe should go back to their homeland, too, where they would finally be safe from pogroms and expulsions.

In 1862, Rabbi Kalischer collected his ideas and plans in a book called Drishat Tzion. In this book he outlined, among other things, the need to build a Jewish agricultural school in Israel, and to create a Jewish military force to protect Israel’s inhabitants. He concluded that the salvation of the Jewish people, as prophesied in the Tanakh, would only come about when Jews start helping themselves instead of relying entirely on God and waiting passively. God is waiting for us to make the first move and show our deep yearning to return to our land, much like God had waited for Israel to make the first move at the Splitting of the Sea, as per the famous Midrash (see Nachshon ben Aminadav). Rabbi Kalischer’s activism was successful, and in 1870 the Mikveh Israel agricultural school was opened on a tract of land now within the boundaries of modern Tel-Aviv.

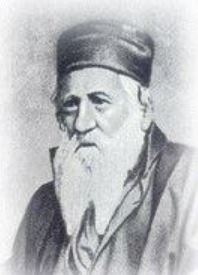

Rabbi Yehuda Alkali

Finally, the most influential proto-Zionist was Rabbi Yehuda Alkali (1798-1878), whom some scholars actually credit with being the true founder of Zionism. Rabbi Alkali studied under the great Sephardi kabbalists of Jerusalem, and went on to serve as a chief rabbi in Serbia. It was the 1840 Damascus Affair that inspired him to take up the cause of aliyah. That summer, 13 Jews in Damascus were arrested following a baseless blood libel accusation. Riots followed, resulting in attacks on Jews, the capture of 63 Jewish children, and the destruction of a synagogue. The imprisoned Jews were tortured to try to get them to confess. Four of the 13 Jews died during that torture, so it isn’t surprising that seven others ultimately “confessed” to the absurd crime.

The international community was aware of what was going on, and the story was covered by Western media. Many governments attempted to intervene and stop the madness. A Jewish delegation—led by Moses Montefiore—was sent to deliberate with the authorities in Damascus. They were ultimately successful, and the nine surviving Jewish prisoners were exonerated and freed.

Rabbi Alkali was horrified at these events, and saw how Christians and Muslims in Syria had conspired together against the Jews. This was the last straw for him. By a stroke of fate, he happened to meet Rabbi Bibas right around this time. The conclusion was obvious: the Jews must have a strong state of their own. There was no other way to prevent the ludicrous, unceasing anti-Semitism and persecution of Jews. That same year Rabbi Alkali established the Society for the Settlement of Eretz Yisrael. It was 1840, or 5600 on the Hebrew calendar, precisely the year that the Zohar prophesied to be the start of the Redemption (see ‘The Zohar’s Prophecy of Another Great Flood’ in Garments of Light).

Incredibly, Rabbi Alkali made a prophecy of his own based on the words of the Zohar: that the Jews have exactly one hundred years to bring about the Redemption. If Jews do not take on this challenge, he warned, then God would bring about the Redemption anyway, but through much more difficult means, through “an outpouring of wrath”. Of course, this is exactly what had happened one hundred years later.

In 1857, Rabbi Alkali published Goral L’Adonai (named after the Biblical lots—goral in Hebrew—that the Israelites cast before settling the Holy Land). This was a step-by-step manual for how to re-establish a Jewish state in Israel. In it, he proposed the resurrection of Hebrew as the spoken language of all Jews, the piece-by-piece purchase of the Holy Land from the Ottomans, and the necessity of the Jews to return to an agrarian lifestyle and work their own land. All of these would, of course, materialize in the coming decades.

It is with this book of Rabbi Alkali that the Zionist story comes full circle. Rabbi Alkali was the chief rabbi of the town of Semlin in Serbia. One of the congregants of his Semlin synagogue was a man named Simon Loeb Herzl, a dear friend of his. Rabbi Alkali presented one of the first copies of Goral L’Adonai to him. Three years later, Simon Loeb Herzl welcomed a new grandson: Theodor. It was in his grandfather’s study that a young Theodor Herzl came across Goral L’Adonai, and it was this work, scholars now conclude, that planted the seeds of Zionism in his mind.

By that point, the foundations of the Jewish State had already been laid by Rabbis Alkali and Bibas, by Moses Montefiore, and by the many that they had inspired, including Rabbi Kalischer. And so, Zionism did not begin as a secular Ashkenazi movement at all, and instead began, quite ironically, as a religious Sephardi movement. Of course, it was the Ashkenazis that took the movement to the next level, and without that great push the Jewish State would not have materialized.