Towards the end of this week’s Torah portion, Beha’alotcha, we read that “Miriam and Aaron spoke against Moses because of the Cushite woman whom he had married, for he had married a Cushite woman.” (Numbers 12:1) This verse brings up many big questions, and the Sages grapple with its meaning. Who is this Cushite woman? When did Moses marry her? Why did Miriam and Aaron speak “against” Moses because of her? Why the superfluous phrasing of mentioning twice that he married the Cushite woman? What does “Cushite” even mean?

Traditionally, there are two main ways of looking at this passage: either Moses actually took on a second wife in addition to his wife Tzipporah, or the term “Cushite” simply refers to Tzipporah herself. The second interpretation is problematic, since we know Tzipporah was a Midianite, not a Cushite. The term “Cushite” generally refers to the people of Cush, or Ethiopia, and more broadly refers to all black people or Africans. Scripture does connect the Cushites with the Midianites in one verse (Habakkuk 3:7), which some use as proof that the Midianites were sometimes referred to as Cushites, or had particularly dark skin.

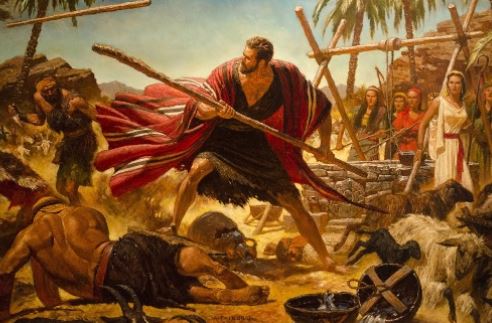

‘The Fight at Jethro’s Well’ – where Moses first meets Tzipporah – scene from ‘The Ten Commandments’ (1953) painted by Arnold Friberg.

Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105) prefers the second interpretation. He says that Tzipporah was called a “Cushite” because she was very beautiful. He cites Midrash Tanchuma in stating that just as everyone can immediately identify a black person (Cushite), everyone immediately recognized the incomparable beauty of Tzipporah. The same Midrash offers another possibility: apparently if a person had a very beautiful child in those days, they would call them “Cushite” to ward off the evil eye. This suggests that a Cushite was not considered beautiful at all, yet Rashi provides a numerical proof that Cushite does indeed mean “beautiful”, since the gematria of Cushite (כושית) is 736, equal to “beautiful in appearance” (יפת מראה), the term frequently used in the Torah to describe beauty.

If the Cushite is Tzipporah, then why did Miriam and Aaron suddenly have a problem with her? Rashi cites one classic answer: because Moses had become so holy—recall how after coming down Sinai, his skin glowed with such a blinding light that he had to wear a mask over his face—he had essentially removed himself from this material world. This means he was no longer intimate with his wife Tzipporah. Miriam had learned of this, and thought Moses was in error for doing so.

Unlike certain other religions, Judaism does not preach celibacy, and does not require complete abstinence to remain holy and pure. Conversely, Judaism holds that sexual intimacy is an important aspect of spiritual growth. The famous Iggeret HaKodesh (the “Holy Letter”, often attributed to the Ramban, Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270, but more likely written by Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla, 1248-1305) writes that it is specifically during sexual union (if done correctly and in holiness) that a man and woman can bring down and experience the Shekhinah, God’s divine presence.

As such, Miriam and Aaron came to their little brother and admonished him for separating from his wife. This is why the Torah goes on to state that “They said, ‘Has God spoken only to Moses? Hasn’t He spoken to us too?’” (Numbers 12:2) Miriam and Aaron argued that they, too, were prophets, and they clearly had no need to separate from their own spouses! Moses was so humble and modest that he did not respond at all: “…Moses was exceedingly humble, more so than any person on the face of the earth.” (Numbers 12:3)

God immediately interjected and summoned Miriam and Aaron to the Ohel Mo’ed, the “Tent of Meeting”, where He regularly conversed with Moses. God told them:

If there be prophets among you, I will make Myself known to him in a vision; I will speak to him in a dream. Not so My servant Moses; he is faithful throughout My house. With him I speak mouth to mouth; in [plain] sight and not in riddles, and he beholds the image of the Lord…

God makes it clear to Miriam and Aaron that although they are also prophets, they are nowhere near the level of Moses. In all of history, Moses alone was able to speak to God “face to face”, while in a conscious, awake state. All other prophets only communed with God through dreams or visions, while asleep or entranced.

By juxtaposing the fact that Moses was the humblest man of all time, and also the greatest prophet of all time, the Torah may be teaching us that the key to real spiritual greatness is humility. Moses had completely subdued his ego, and so he merited to be filled with Godliness. Fittingly, the Talmud (Sotah 5a) states that where there is an ego, there cannot be a Godly presence, because a person with a big ego essentially sees themselves as a god—and there cannot be two gods! “Every man in whom there is haughtiness of spirit, the Holy One, blessed be He, declares: ‘I and he cannot both dwell in the world.’”

Moses Had a Black Wife

The explanation above is certainly a wonderful one, yet it is hard to ignore the plain meaning of the text: that Moses actually married a Cushite woman. The repetitive phrasing of the verse seems like it really wants us to believe he had taken another wife. And many of the Sages agree. However, Moses hadn’t married her at this point in time, but many years earlier. The Midrash describes in great detail what Moses was up to between the time that he fled Egypt and arrived in Midian. After all, he had fled as a young man, and returned to Egypt in his 80th year. What did he do during all those intervening decades?

The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Shemot 168) says that Moses initially fled to Cush. At the time, the Cushites had lost their capital in a war and were unsuccessful in recapturing it. Their king, named Koknus (קוקנוס, elsewhere called Kikanos or Kikianus), fought a nine-year war that he was unable to win, and then died. The Cushites sought a strong ruler to help them finally end the conflict. They chose Moses, presumably because he had fought alongside the Cushites and had a reputation as a great warrior. Moses did not disappoint, and devised a plan to win the war and recapture the Cushite capital. (His enemy was none other than Bilaam!) The grateful Cushites gave Moses the royal widow of Koknus for a wife, and placed him upon the throne.

Charlton Heston as Egyptian General Moses, also by Arnold Friberg

This Midrash is very ancient, and was already attested to by the Jewish-Roman historian Josephus (37-100 CE). Josephus writes (Antiquities, II, 10:239 et seq.) a slightly different version of the story, with Moses leading an Egyptian army against the Cushites. The Cushite princess, named Tharbis, watches the battle and falls in love with the valiant Moses. She goes on to help him win the battle, and he fulfils his promise in return to marry her. In some versions, Moses eventually produces a special ring that causes one to forget certain events, and puts it upon Tharbis so that she can forget him. He then returns to Egypt.

So, Moses married a Cushite queen. Yet, he remembered “what Abraham had cautioned his servant Eliezer” about intermarriage, and abstained from touching her. (If you are wondering how Moses later married Tzipporah, who was not an Israelite, remember that the Midianites are also descendants of Abraham through his wife Keturah, see Genesis 25:2. Thus, Moses still married within the extended family of Abrahamites.) Although Moses married the Cushite queen, he never consummated the marriage. The Midrash says he reigned over a prosperous Cush for forty years until his Cushite wife couldn’t take the celibacy anymore and complained to the wise men of Cush. Moses abdicated his throne and finally left Ethiopia. He was 67 years old at the time.

All of this was kept secret until it came out publicly in this week’s parasha. This is a terrific version of the story, but it doesn’t answer why Miriam and Aaron complained to Moses. For this we must look to the mysticism of the Arizal.

Soulmates of Moses

The Arizal cites the above Midrash in a number of places (see Sefer Likutei Torah and Sha’ar HaPesukim on this week’s parasha, as well as Sha’ar HaMitzvot on parashat Shoftim). He explains that both Tzipporah and the Cushite were Moses’ soulmates. This is because Moses was a reincarnation of Abel, who had two wives according to one tradition. This was the reason for the dispute between Cain and Abel, resulting in the latter’s death. Cain was born with a twin sister, and Abel was born with two twin sisters (otherwise, with whom would they reproduce?) Cain reasoned that he should have two wives since he was the older brother, and the elder always deserves a double portion. Abel reasoned that he should have the second wife since, after all, she was his twin! Cain ultimately killed Abel over that second wife.

Therefore, the Arizal explains that Cain reincarnated in Jethro, and Abel in Moses. This is why Jethro gave his daughter Tzipporah to Moses, thus rectifying his past sin by “returning” the wife that he had stolen.* Moses’ other spiritual twin was the Cushite woman. The Arizal suggests that Miriam and Aaron were aware of this, and were frustrated that Moses did not consummate his marriage to the Cushite, for she was his true soulmate! Apparently, after the Exodus Moses summoned the Cushite woman and she happily joined the Israelites and converted to Judaism. The Arizal explains that this was a necessary tikkun, a spiritual rectification for her lofty soul. However, he could not consummate the marriage because her soul originated from a place of intense dinim gemurim, strict judgement and severity. It appears that when Miriam heard about his abstention from his wife, she complained to Moses, failing to grasp that a soul as pure as Moses’ had different requirements.

Whatever the case may be, the root of the matter is Moses’ separation from his wife (or wives). Having said all that, there is a third possibility. This comes from a simple reading of the Torah text, and the lesson that we learn from it is particularly relevant today.

Black or White

When we read the first two verses of Numbers 12 in isolation, we might be led to believe that Miriam and Aaron had a problem with Moses marrying a black woman. Was there a hint of racism in their complaint, or did they just genuinely wonder whether an Israelite was allowed to marry a black person? Either way, we see how perfectly the punishment fits the crime: “… Behold, Miriam was afflicted with tzara’aat, [as white] as snow.” (Numbers 12:10)

If the issue was about Moses separating from his wife, it isn’t clear why Miriam would be punished with tzara’at (loosely translated as “leprosy”). Rashi, for one, does not seem to offer a clear explanation why this in particular was her punishment. Of course, we know that God doesn’t really “punish”, and simply metes out justice, middah k’neged middah, “measure for measure”. It is therefore totally fitting that in complaining about Moses taking a black woman as a wife, Miriam’s own skin is turned white “like snow”. Perhaps God wanted to remind her that she is not so white herself.

We can learn from this that there really is no place for racism in Judaism. In fact, God explicitly compares the Israelites to the Cushites (Amos 9:7), and maintains that He is not the God of the Jews alone, but the God of all peoples: “‘Are you not as the children of the Cushites unto Me, O children of Israel?’ Said Hashem. ‘Have I not brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt, [just as I brought] the Philistines from Caphtor, and Aram from Kir?’” Among a list of nine holy people that merited to enter Heaven alive, without ever dying, the Sages include a Cushite man named Eved-Melekh (Derekh Eretz Zuta 1:43, see Jeremiah 39:16).

At the end of the day, there is no reason to hold prejudice against anyone, or discriminate against any individual at all, as the Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Shoftim 42) clearly states:

I bring Heaven and Earth to witness that the Divine Spirit may rest upon a non-Jew as well as a Jew, upon a woman as well as a man, upon a maidservant as well as a manservant. All depends on the deeds of the particular individual.

*The Arizal actually writes how Cain reincarnated in three people: Korach, Jethro, and the Egyptian taskmaster that Moses killed before fleeing Egypt. The rectification for the improper dispute between Cain and Abel was rectified in the dispute between Korach and Moses, with Moses’ victory. The rectification for the stolen wife was fulfilled by Jethro. And the rectification for Cain murdering Abel was that Moses, in return, killed the Egyptian taskmaster. Thus, all the rectifications were complete. We can see a hint in the name Cain (קין) to his three future incarnations: the ק for Korach (קרח), the י for Jethro (יתרו), and the ן for the Egyptian, whose name we don’t know but perhaps it started with a nun!