“And it will be, when you come into the land which YHWH, your God, gives you for an inheritance, and you possess it and settle in it…” (Deuteronomy 26:1)

This week’s parasha, Ki Tavo, begins with the command for Israel to go to the Holy Land, possess it, inherit it, work the land, and then give thanks for its wonderful produce. The Torah is clear on the fact that the Jewish people belong in the Land of Israel. In fact, the Talmud (Ketubot 110b) states that a Jew who lives outside of Israel is likened to an atheist that doesn’t have a God:

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: לְעוֹלָם יָדוּר אָדָם בְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲפִילּוּ בְּעִיר שֶׁרוּבָּהּ גּוֹיִם, וְאַל יָדוּר בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ וַאֲפִילּוּ בְּעִיר שֶׁרוּבָּהּ יִשְׂרָאֵל, שֶׁכׇּל הַדָּר בְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל דּוֹמֶה כְּמִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ אֱלוֹהַּ, וְכׇל הַדָּר בְּחוּצָה לָאָרֶץ דּוֹמֶה כְּמִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ אֱלוֹהַּ. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״לָתֵת לָכֶם אֶת אֶרֶץ כְּנַעַן לִהְיוֹת לָכֶם לֵאלֹהִים״

The Sages taught: A person should always reside in the Land of Israel, even in a city that is mostly populated by gentiles; and should not reside outside of Israel, even in a city that is mostly populated by Jews, because anyone who resides in Israel is considered as one who has a God, and anyone who resides outside of Israel is considered as one who does not have a God, as it is stated: “To give to you the land of Canaan, to be your God.” (Leviticus 25:38)

The Talmud then challenges this statement, arguing that it can’t be that living outside of Israel makes a Jew an atheist. So, it gives a better answer: “Anyone who lives outside of Israel is likened to an idolater!” At this point, we are presented with a story about how Rabbi Zeira really wanted to make aliyah, but his teacher Rav Yehuda disapproved. Rav Yehuda took the following verse quite literally: “They shall be taken to Babylonia and there they shall remain until the day that I recall them, said the Lord.” (Jeremiah 27:22) Rav Yehuda believed leaving Babylon for Israel without a clear sign from God was a transgression.

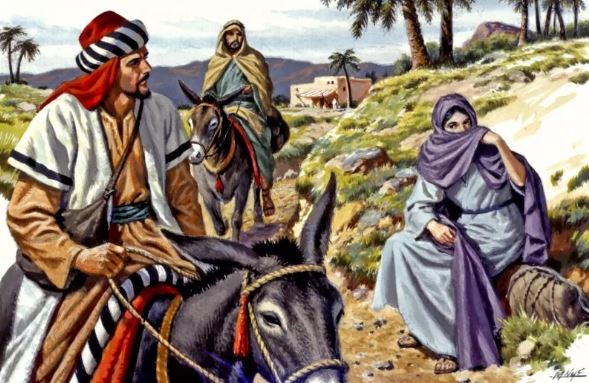

‘The Flight of the Prisoners’ by James Tissot, depicting the Jewish people’s exile after the destruction of the First Temple.

Of course, that verse in Jeremiah is speaking of the period between the First and Second Temples, and had no direct relevance to Rav Yehuda’s generation many centuries later. But this was not the approach that Rabbi Zeira took to refute his teacher’s position. Instead, he reminded Rav Yehuda that the previous verse in Jeremiah is “concerning the vessels that remain in the house of the Lord”. The whole thing is clearly talking about the Temple items, not about the Jewish people, who are always welcome in their own Promised Land.

Rav Yehuda changes course and rebuts with a different verse from Tanakh: “I adjure you [ishba’ati], O daughters of Jerusalem, by the gazelles and by the hinds of the field, that you not awaken nor stir up love, until it please.” (Song of Songs 2:7) He uses this as proof that Jews shouldn’t go back to Israel until it pleases God. Rabbi Zeira counters that this verse refers to an oath (shvu’a, based on the term ishba’ati) that the Jewish nation apparently took upon themselves when going into exile. There are actually three verses in Shir haShirim (2:7, 3:5, 8:4) that begin the exact same way, with the same ishba’ati word that implies an oath. Thus, there were three oaths that God adjured:

First, that the Jewish people should not return to Israel en masse, “like a wall”, through an organized political or social movement. Second, that the Jewish people should not rebel in exile against their gentile overlords. The third oath was that, in turn, the gentile nations would not oppress the Jews too much. In other words, Jews should be allowed to live in relative peace and safety among the gentiles, in exchange for not seeking to go back “like a wall” to the Holy Land. So, Rabbi Zeira believes that while large groups and mass movements of Jews should not make aliyah en masse, individuals and families could make aliyah to Israel if they wish. Rabbi Zeira thus argued that it was permissible for him to move to Israel.

Rav Yehuda didn’t give up, and countered that the phrasing of “not waken nor stir up” in the Shir haShirim verse implies both large groups and individuals. At this point, Rabbi Levi enters the fray and says that the extra language is for a different reason: each oath is actually two oaths, and there are a total of six oaths, not three! The extra three oaths are that Jewish scholars should not reveal when the End of Days and the Final Redemption would come; but that they should also not “distance” the Final Redemption and cause it to be postponed; and finally that Jews shouldn’t reveal “the secret” to the nations of the world. It is unclear what exactly this “secret” is. Rashi suggests it refers to the secrets of the divine Jewish calendar and intercalation of months (as does Yalkut Shimoni II, 986), or perhaps the deeper mystical secrets of the Torah. One might also read it simply as not revealing the secret time of the Redemption to anyone, Jew or gentile.

The Talmud then explains what is the meaning of the latter words in the Shir haShirim verse, “by the gazelles and by the hinds of the field.” Rabbi Elazar quotes God saying to the Jewish people: “If you fulfill the oath, it is good, and if not, I will abandon your flesh ‘like the gazelles and like the hinds of the field.’” In other words, if we don’t fulfil the oath, we will be left alone in the field, without any divine protection, presumably to be hunted down like gazelles. Then Rabbi Elazar adds one final statement before the Talmud moves on to a different discussion about burial: “Anyone who resides in the Land of Israel dwells without transgression…” So, what do we make of this puzzling passage?

Violating Oaths, Fulfilling Oaths

On the surface, the Talmud seems to be telling us that Rav Yehuda held that Jews shouldn’t seek to live in Israel until the coming of Mashiach and the Final Redemption. Rabbi Zeira, on the other hand, believed that Jews should move to Israel and it is praiseworthy for them to do so—but they should immigrate individually, and not as a mass movement. This is evidently the majority position of the Talmudic sages, since the whole passage begins by saying that any Jew who doesn’t live in Israel is an atheist or idolater, and goes on to say how wonderful it is for a Jew to live in Israel. Rabbi Elazar’s concluding opinion is most intriguing, and seems to suggest that while he also agrees Jews shouldn’t move to Israel en masse, if they have already done so anyway then, bedieved, it is fine and they are sinless.

In the previous century, many Hasidic and Haredi rabbis took an anti-Zionist stance because of this Talmudic passage of the “Three Oaths”. Yet, ironically, some of the earliest figures who made aliyah to Israel en masse, “like a wall”, were actually Hasidim and Haredim! (For more on this, see the class on ‘The Hidden History of Zionism’.) The first was probably Rabbi Yehuda haHasid Segal (c. 1660-1700) who led a group of 1200 Jews to Israel from across Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire in 1697. Then came 300 Hasidim with Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk (c. 1730-1788) in 1777. In 1808 arrived someone from the opposite side of the spectrum, the Litvish Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Shklov (d. 1827), a disciple of the Vilna Gaon, who brought with him 150 Mitnagdim. Meanwhile, the Sefardi world, led by Sir Moses Montefiore, Rabbi Yehuda Alkali, and Rabbi Yehuda Bibas, sent many more Jews to Israel throughout the 1800s. And, of course, the First Aliyah (which began in 1881 and totalled some 25,000 people) was made up almost entirely of Hasidim fleeing the pogroms of the Russian Empire! And this brings us back to the Three Oaths.

The Oaths state that Jews would remain in exile without protest on condition that the nations would not oppress Israel too harshly. Clearly, history shows that the nations did not uphold their end of the deal. Jews were tormented endlessly and brutally, whether by Crusaders or Inquisitors, Almohads, Cossacks, or Nazis. It is clear that the Oaths were violated by the nations, and thus rendered null and void. Jews had no choice but to move to Israel en masse.

The first major wave actually came following the Spanish Expulsion of 1492. It was those Sephardic Jews—coming in the many thousands—that rebuilt the four holy cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Tzfat, and Tiberias and re-established vibrant communities there in the 16th century. There would be no Shulchan Arukh and no Kitvei Arizal and no Lecha Dodi (all of which were composed in 16th-century Tzfat) were it not for the “wall” of Sephardim that migrated there. The “wall” of religious Jews that came in the 1800s and early 1900s set the foundations for the modern State of Israel, and established some of the most religious Jewish neighbourhoods in the world like Mea Shearim and Bnei Brak.

So, it seems no one made a particularly big deal about the Three Oaths until recently. It was just a little-known idea from a short passage in the Talmud that is almost never mentioned in any other ancient texts. In fact, it wasn’t until Religious Zionism was hijacked by more secular Political Zionism that people started to remember the old Talmudic oaths. Now, one might argue those oaths don’t matter anyway because they are not halakhah, and just part of a personal debate between Rav Yehuda and Rabbi Zeira. (After all, the Jews never literally took any such oaths, and neither did the nations of the world.) However, even if one goes with the position that the oaths were firm and binding, the modern State of Israel still does not violate them.

The Maharsha (Rabbi Shmuel Eidels, 1555-1631) comments here on Ketubot 111a (appropriately, in his Chiddushei Aggadot, not Chiddushei Halakhot!) that there is an exception to ascending “like a wall” to Israel. He connects the mysterious term “like a wall”, chomah, to Nehemiah 2:17, where Nehemiah says to the exiled Jews: “You see the bad state we are in—Jerusalem lying in ruins and its gates destroyed by fire. Come, let us rebuild the wall of Jerusalem [chomat yerushalayim] and suffer no more disgrace.” The Maharsha asks how could it be that Nehemiah was inspiring thousands of Jews to return to Israel “like a wall” and rebuild it? Doesn’t this violate the oath? The Maharsha answers that it didn’t violate the oath because Nehemiah had the king’s permission to do so. This was not an act of rebellion against the nations! Which brings us back to the case of modern Israel.

The Jews that were returning to Israel en masse, starting in the 15th century, were doing so with the full permission of the Ottoman Empire who ruled over the land. In fact, Don Joseph Nasi (1524-1579) was given a charter by the Ottomans to recreate a semi-autonomous Jewish state with its capital in Tiberias, and was given the official title “Lord of Tiberias”. This is essentially the same situation as Nehemiah was in. The Jews in the 1800s were similarly buying plots of land from the Ottomans legally. Then the British took over and became the new overlords of the land. The Balfour Declaration demonstrated the intent of the British to establish a Jewish state in the Holy Land. The San Remo Conference of 1920 adopted and affirmed the Balfour Declaration, with the international powers agreeing to establish a Jewish state in Israel. And finally, the UN voted to establish a Jewish state in November 1947 through the consensus of a majority of nations. (As many have pointed out, far from being an “illegal occupier”, the State of Israel is possibly the most legal state on the planet!) Thus, the creation of the modern State of Israel would mirror the times of Nehemiah and, according to the reasoning of the Maharsha, would not be a violation of the Three Oaths.

Finally, if we go back to the Scriptural source for the Three Oaths, the verses say that we shouldn’t “awaken until it pleases” God. How exactly would we know if it pleases God? Perhaps through a series of miracles and signs? Supernatural occurrences and clear divine favour? Does modern Israel not fit the bill? Turning swamps and deserts into high-tech metropolises, re-establishing forests with literally hundreds of millions of new trees, exporting fruit to the world, desalinating water so that the land and its people no longer have to worry about being parched, and fighting off wave after wave of attack from aggressive neighbours. Do we ignore the miracles of 1948 and 1967 and 1973? Did we forget all the prophecies in Tanakh that have come true right before our eyes? How many more signs do we need to confirm that, indeed, “it pleases God”?

It hasn’t been easy, of course, and there has been a great deal of suffering along the way, but it was never meant to be easy, and Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai told us long ago that three gifts are acquired through pain: “The Holy One, Blessed be He, gave Israel three precious gifts, all of which were given only by means of suffering: Torah, the Land of Israel, and the World to Come.” (Berakhot 5a) We have thankfully already received the first two gifts. Hopefully, the suffering we are experiencing now as a nation is the necessary bit of pain before the third and final gift which is right around the corner.