This week’s parasha, Korach, describes the rebellion instigated by Moses’ Levite cousin Korach. Korach’s main accusation was against Aaron and the Kohanim: why did they tale all the priestly services for themselves and left nothing for the lay Israelite? Had not God stated that all of Israel will be a holy nation of kohanim? (Exodus 19:6) Why did only a small group of people (Aaron and his descendants) suddenly become kohanim? His argument was actually a valid one, and Rashi (on Numbers 16:6) records that Moses even agreed with Korach to some extent, and said that he too wishes that all of Israel could be priests! Why weren’t they?

Tag Archives: Levites

The Difference between “Jew” and “Hebrew”

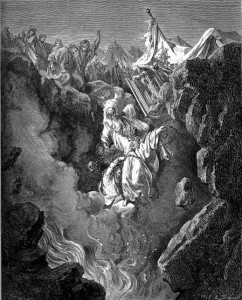

“Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram” by Gustave Doré

This week’s parasha is named after Korach, the rebellious cousin of Moses. Korach felt he had been unfairly slighted. Moses had apparently made himself like a king over the people, then appointed his brother Aaron as high priest. The final straw was appointing another cousin, the younger Elitzaphan, as chief of the Kohatites, a clan of Levites of which Korach was an elder. Where was Korach’s honour?

Korach’s co-conspirators were Datan and Aviram, leaders of the tribe of Reuben. They, too, felt like they’d been dealt a bad hand. After all, Reuben was the eldest son of Jacob, and as the firstborn among the tribes, should have been awarded the priesthood.

The Sages explain that Reuben indeed should have held the priesthood. Not only that, but as the firstborn, he should have also been the king. Reuben, however, had failed in preventing the sale of Joseph, and had also committed the unforgivable sin of “mounting his father’s bed”. For this latter crime especially, and for being “unstable like water”, Jacob declared that Reuben would “not excel” or live up to being “my first fruit, excelling in dignity, excelling in power” (Genesis 49:3-4).

Instead, the status of “firstborn” was awarded to Joseph, who had taken on the mantle of leadership and saved his entire family in a time of terrible drought. Jacob made Joseph the firstborn, and thus gave Joseph a double portion among the Tribes and in the land of Israel. He put Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Menashe in place of his own firsts Reuben and Shimon (Genesis 48:5). Meanwhile, the excellence of “dignity”—the priesthood—went to the third-born son, Levi, and the excellence of power—royalty—went to the fourth son, Judah. (The second-born Shimon was skipped over because he, too, had greatly disappointed his father in slaughtering the people of Shechem, as well as spearheading the attempt to get rid of Joseph.)

Levi merited to hold the priesthood because the Levites were the only ones not to participate in the Golden Calf incident (Exodus 32:26). The Book of Jubilees (ch. 32) adds a further reason: Jacob had promised to God that he would tithe everything God gave him (Genesis 28:22), and everything included his children. Jacob thus lined up his sons, and counted them from the youngest up. The tenth son, the tithe, was Levi (who was the third-oldest, or “tenth-youngest”, of the twelve). And so, Levi was designated for the priesthood, to the service of God.

Judah merited the royal line for his honesty and repentance—particularly for the sale of Joseph, and for the incident with Tamar. He further established his leadership in taking the reins to safely secure the return of Benjamin. The name Yehudah comes from the root which means “to acknowledge” and “to be thankful”. Judah acknowledged his sins and purified himself of them. Ultimately, all Jews would be Yehudim, the people who are dedicated to repentance and the acknowledgement and recognition of Godliness in the world. Much of a Jew’s life is centered on prayers and blessings, thanking God every moment of the day, with berakhot recited before just about every action. The title Yehudi is therefore highly appropriate to describe this people. Yet, it is not the only title.

Long before Yehudi, this people was known as Ivri, “Hebrew”, and then Israel. What is the meaning of these parallel names?

Hebrew: Ethnicity or Social Class?

The first time we see the term “Hebrew” is in Genesis 14:13, where Abraham (then still called Abram) is called HaIvri. The meaning is unclear. The Sages offer a number of interpretations. The plain meaning of the word seems to mean “who passes” or “who is from the other side”. It may refer to the fact that Abraham migrated from Ur to Charan, and then from Charan to the Holy Land. Or, it may be a metaphorical title, for Abraham “stood apart” from everyone else. While the world was worshipping idols and living immorally, Abraham was “on the other side”, preaching monotheism and righteousness.

An alternate approach is genealogical: Ever was the name of a great-grandson of Noah. Noah’s son Shem had a son named Arpachshad, who had a son named Shelach, who had a son named Ever (see Genesis 11). In turn, Ever was an ancestor of Abraham (Ever-Peleg-Reu-Serug-Nachor-Terach-Abraham). Thus, Abraham was called an Ivri because he was from the greater clan of Ever’s descendants. This must have been a powerful group of people recognized across the region, as attested to by Genesis 10:21, which makes sure to point out that Shem was the ancestor of “all the children of Ever”. Amazingly, archaeological evidence supports this very notion.

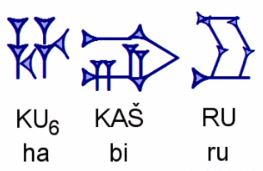

“Habiru” in ancient cuneiform

From the 18th century BCE, all the way until the 12th century BCE, historical texts across the Middle East speak of people known as “Habiru” or “Apiru”. The Sumerians described them as saggasu, “destroyers”, while other Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts describe them as mercenary warriors, slaves, rebels, nomads, or outlaws. Today, historians agree that “Habiru” refers to a social class of people that were somehow rejected or outcast from greater society. These were unwanted people that did not “fit in”. That would explain why Genesis 43:32 tells us that Joseph ate apart from the Egyptians, because “the Egyptians did not eat bread with the Hebrews; for that was an abomination to the Egyptians.”

One of the “Habiru” described in Egyptian texts are the “Shasu YHW” (Egyptian hieroglyphs above), literally “nomads of Hashem”. Scholars believe this is the earliest historical reference to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name, YHWH.

Defining “Hebrew” as an unwanted, migrating social class also solves a number of other issues. For example, Exodus 21:2 introduces the laws of an eved Ivri, “a Hebrew slave”. When many people read this passage, they are naturally disturbed, for it is unthinkable that God would permit a Jew to purchase another Jew as a slave. Yet, the Torah doesn’t say that this is a Jew at all, but an Ivri which, as we have seen, may refer to other outcasts from an inferior social class. The Habiru are often described as slaves or servants in the historical records of neighbouring peoples, so it appears that the Torah is actually speaking of these non-Jewish “Hebrews” that existed at the time. Regardless, the Torah shows a great deal of compassion for these wanderers, and sets limits for the length of their servitude (six years), while ensuring that they live in humane conditions.

Rebels and Mystics

Though he was certainly no slave or brigand, Abraham was undoubtedly a “rebel” in the eyes of the majority. To them, he was a “criminal”, too, as we read in the Midrash describing his arrest and trial by Nimrod the Babylonian king. Abraham spent much of his life wandering from one place to another, so the description of “nomad” works. So does “warrior”, for we read of Abraham’s triumphant military victory over an unstoppable confederation of four kings that devastated the entire region (Genesis 14). There is no doubt, then, that Abraham would have been classified as a “Habiru” in his day.

His descendants carried on the title. By the turn of the 1st millennium BCE, it seems that all the other Ivrim across the region had mostly disappeared, and only the descendants of Abraham, now known as the Israelites, remained. The term “Hebrew”, therefore, became synonymous with “Israelite” and later with Yehudi, “Judahite” or “Jew”. (This is probably why later commentators simply assumed that the Torah was speaking about Jewish slaves in the Exodus 21 passage discussed above.) To this day, in many cultures and languages the term for a “Jew” is still “Hebrew”. In Russian it is yivrei, in Italian it is ebreo, and in Greek evraios. In other cultures, meanwhile, “Hebrew” is used to denote the language of the Jews. It is Hebrew in English, hebräisch in German, hébreu in French.

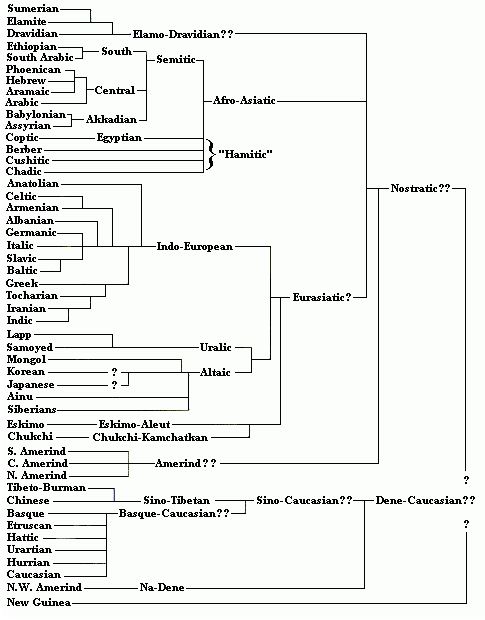

In fact, another rabbinic theory for the origins of the term Ivri is that it refers specifically to the language. In Jewish tradition, Hebrew is lashon hakodesh, “the Holy Tongue” through which God created the universe when He spoke it into existence. The language contains those mystical powers, and because the wicked people of the Tower of Babel generation abused it, their tongues were confounded in the Great Dispersion. At that point, God divided the peoples into seventy new ethnicities, each with its own language, giving rise to the multitude of languages and dialects we have today.

A possible language tree to unify all of the world’s major tongues, based on the work of Stanford University Professor Joseph Greenberg. (Credit: angmohdan.com)

Hebrew did not disappear, though. It was retained by the two most righteous people of the time: Shem and Ever. According to tradition, they had built the first yeshiva, an academy of higher learning. Abraham had visited them there, and Jacob spent some fourteen years studying at their school. The Holy Tongue was preserved, and Jacob (who was renamed Israel) taught it to his children, and onwards it continued until it became the language of the Israelites.

Alternatively (or concurrently), Abraham learned the Hebrew language from his righteous grandfather Nachor, the great-grandson of Ever. We read of the elder Nachor (not to be confused with Nachor the brother of Abraham) that he had an uncharacteristically short lifespan for that time period (Genesis 11:24-25). This is likely because God took him away so that he wouldn’t have to live through the Great Dispersion. (Nachor would have died around the Hebrew year 1996, which is when the Dispersion occurred. The Sages similarly state that God took the righteous Methuselah, the longest-living person in the Torah, right before the Flood to spare him from the catastrophe.)

Interestingly, we don’t see much of an association between the Hebrew language and the Hebrew people in the Tanakh. Instead, the language of the Jews is called, appropriately, Yehudit, as we read in II Kings 18:26-28, Isaiah 36:11-13, Nechemiah 13:24, and II Chronicles 32:18. The term Yehudit may be referring specifically to the dialect of Hebrew spoken by the southern people of Judah, which was naturally different than the dialect used in the northern Kingdom of Israel.

Israel and Jeshurun

The evidence leads us to believe that “Hebrew” was a wider social class in ancient times, and our ancestors identified themselves (or were identified by others) as “Hebrew”. This was the case until Jacob’s time. He was renamed Israel, and his children began to be referred to as Israelites, bnei Israel, literally the “children of Israel”. The twelve sons gave rise to an entire nation of people called Israel.

The Torah tells us that Jacob was named “Israel” because “he struggled with God, and with men, and prevailed” (Genesis 32:29). Jewish history really is little more than a long struggle of Israel with other nations, and with our God. We stray from His ways so He incites the nations against us to remind us who we are. Thankfully, throughout these difficult centuries, we have prevailed.

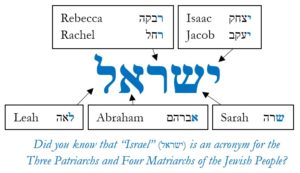

Within each Jew is a deep yearning to connect to Hashem, hinted to in the name Israel (ישראל), a conjunction of Yashar-El (ישר-אל), “straight to God”. This is similar to yet another name for the people of Israel that is used in the Tanakh: Yeshurun. In one place, Moses is described as “king of Yeshurun” (Deuteronomy 33:5), and in another God declares: “Fear not, Jacob my servant; Yeshurun, whom I have chosen.” (Isaiah 44:2) Yeshurun literally means “upright one”. This is what Israel is supposed to be, and why God chose us to begin with. “Israel” and “Yeshurun” have the same three-letter root, and many believe these terms were once interchangeable. The Talmud (Yoma 73b) states that upon the choshen mishpat—the special breastplate of the High Priest that contained a unique stone for each of the Twelve Tribes—was engraved not Shivtei Israel, “tribes of Israel”, but Shivtei Yeshurun, “tribes of Yeshurun”.

What is a Jew?

By the middle of the 1st millenium BCE, only the kingdom of the tribe of Judah remained. Countless refugees from the other eleven tribes migrated to Judah and intermingled with the people there. Then, Judah itself was destroyed, and everyone was exiled to Babylon. By the time they returned to the Holy Land—now the Persian province of Judah—the people were simply known as Yehudim, “Judahites”, or Jews. Whatever tribal origins they had were soon forgotten. Only the Levites (and Kohanim) held on to their tribal affiliation since it was necessary for priestly service.

As already touched on previously, it was no accident that it was particularly the name of Yehuda that survived. After all, the purpose of the Jewish people is to spread knowledge of God, and within the name Yehuda, יהודה, is the Ineffable Name of God itself. This name, like the people that carry it, is meant to be a vehicle for Godliness.

Perhaps this is why the term Yehudi, or Jew is today associated most with the religion of the people (Judaism). Hebrew, meanwhile, is associated with the language, or sometimes the culture. Not surprisingly, early Zionists wanted to detach themselves from the title of “Jew”, and only use the term “Hebrew”. Reform Jews, too, wanted to be called “Hebrews”. In fact, the main body of Reform in America was always called the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. It was only renamed the “Union for Reform Judaism” in 2003!

All of this begs the question: what is a Jew? What is Judaism? Is it a religion? An ethnicity or culture? A people bound by some common history or language? By the land of Israel, or by the State of Israel?

It cannot be a religion, for many Jews want absolutely nothing to do with religion. There are plenty who proudly identify as atheists and as Jews at the same time. We are certainly not a culture or ethnicity, either, for Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardi Jews, Mizrachi Jews, Ethiopian Jews, all have very different customs, traditions, and skin colours. Over the centuries, these groups have experienced very different histories, too, and have even developed dozens of other non-Hebrew Judaic languages (Yiddish, Ladino, Bukharian, and Krymchak are but a few examples).

So, what is a Jew? Rabbi Moshe Zeldman offers one terrific answer. He says that, despite the thousands of years that have passed, we are all still bnei Israel, the children of Israel, and that makes us a family. Every member of a family has his or her own unique identity and appearance, and some members of a family may be more religious than others. Family members can live in distant places, far apart from each other, and go through very different experiences. New members can marry into a family, or be adopted, and every family, of course, has its issues and conflicts. But at the end of the day, a family is strongly bound by much more than just blood, and comes together when it really matters.

And this is precisely what Moses told Korach and his supporters in this week’s parasha. Rashi (on Numbers 16:6) quotes Moses’ response:

Among each of the other nations, there are multiple sects and multiple priests, and they do not gather in one house. But we have none other than one God, one Ark, one Torah, one altar, and one High Priest…

There is something particularly singular about the Jewish people. We are one house. We are a family. Let’s act like one.

Moses and Korach, Abel and Cain, Water and Ice

This week’s Torah reading is named after Moses’ cousin, Korach, and describes his rebellion against the leader of the Jewish people. Rashi’s commentary quotes a number of Midrashic texts to explain Korach’s motivation. Korach was a very wealthy and very wise man. Yet, despite being a distinguished member of the community, and Moses’ cousin, he was not appointed to any prominent roles. The high priesthood was bestowed upon Aaron, while the leadership of the Kohatithes (one of the major divisions of the Levites) was given to Elitzaphan, who was younger than Korach.

Upset by these developments, Korach gathered 250 others and protested: “…the entire congregation, all of them, are holy, and God is in their midst, so why do you raise yourselves above God’s assembly?” (Numbers 16:3) Korach essentially accused Moses of nepotism: putting his own favourites in holy positions to rule over the people, when in reality all the people should be on a high and exalted level, as they are all equally part of God’s assembly.

This was a very good argument, and many were swayed by Korach. After all, God had said to the people that “… you will be a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). Amazingly, Rashi writes that Moses himself agreed with Korach! Moses said:

“Among the nations, there are many forms of worship and many priests, and they do not all gather in one temple. We, however, have only one God, one ark, one Torah, one altar, and one High Priest, but you two hundred and fifty men are all seeking the High Priesthood! I, too, would prefer that. Here, take for yourselves the service most dear [to God] of all: it is the incense, more cherished than any other sacrifice, but it contains deadly poison, by which Nadav and Avihu were burnt, so be warned…” (Rashi on 16:6)

The Incense Offering

The ketoret, or incense offering, was the greatest of Temple services, and could only be performed by the High Priest. It is said that anyone else who attempted it (including the High Priest if he was not in the highest state of purity) would die immediately. The Torah already relayed the story of Nadav and Avihu, the sons of Aaron who tried to bring their own incense, and perished.

“Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram” by Gustave Doré

So, Moses told Korach and his supporters that he would have loved for everyone to be at the level of high priesthood. This is how God had originally intended it after all, and one day in the future it would be so. At the present moment, though, the people were simply not ready for it. If they indeed thought they were all capable of being the High Priest, Moses suggested for them to each bring their own incense. He warned them, though, not to forget what had happened to Nadav and Avihu.

The narrative continues with Korach and his supporters bringing their own incense offering, with the result being utter failure, and every one of them losing their life for it (16:35). Korach himself, together with his main supporters Datan and Aviram, was given a more severe punishment: they were swallowed up by the earth. Interestingly, this specific punishment was decreed by Moses. Why did Moses specifically want Korach to be swallowed up by the earth?

Cain and Abel

The Arizal explains that Moses and Korach were reincarnations of Abel and Cain (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 29 and 32). Cain had risen up against Abel, argued with him, and then murdered him. The text states that the earth had “opened its mouth” to receive Abel’s blood (Genesis 4:11). This time around, Cain’s soul (within Korach) again rose up against Abel’s soul (within Moses) and quarreled with him. Now, to complete the spiritual rectification, measure for measure, it was Abel that buried Cain in the earth, with the text once again saying that the earth had “opened its mouth” (16:32).

Water and Ice

Practically speaking, Moses and Korach represent two types of people, indicated by their names. Moses, Moshe, was a name given by the Pharaoh’s daughter, who said ki min hamayim meshitihu, “For I drew him out of the water.” Korach, on the other hand, has the exact same Hebrew spelling as kerach, ice. Moses represents water; Korach represents ice. The latter is cold, hard, and unyielding, expanding ever larger as it freezes, symbolic of an inflating ego. The former is fluid, life-giving, and always flows to the lowest possible point, symbolic of humility. The lesson here is for each person to emulate the watery traits of Moses, and not the frozen qualities of Korach.