This week’s parasha is Toldot, which begins:

And these are the genealogies [toldot] of Isaac, the son of Abraham; Abraham begot Isaac. And Isaac was forty years old when he took Rebecca… for a wife. And Isaac prayed to Hashem opposite his wife, because she was barren, and Hashem accepted his prayer, and Rebecca his wife conceived.

The Torah juxtaposes Isaac’s marriage to Rebecca with Isaac’s successful prayer. One of the Torah’s central principles of interpretation is that when two ideas or passages are placed side by side, there must be an intrinsic connection between them. What is the connection between marriage and prayer?

Another central principle of interpretation is that when a word or concept appears for the first time in the Torah, its context teaches the very epitome of that word or concept. The first time that the word “love” is used between a man and woman in the Torah is with regards to Isaac and Rebecca, and the two thus represent the perfect marital bond (a topic we’ve explored in the past; see: ‘Isaac and Rebecca: the Secret to Perfect Marriage’ in Garments of Light).

So, we see that Isaac and Rebecca were very successful in their love and marriage, and simultaneously very successful in their prayers. In fact, our Sages teach that when the Torah says “Isaac prayed… opposite his wife”, it means that the two prayed together in unison, and some even say they prayed while in a loving embrace, face-to-face, literally “opposite” one another. God immediately answered their prayers. What is the secret of Isaac and Rebecca’s success in love and prayer?

Understanding Prayer

It is commonly (and wrongly) believed that prayer is about asking God for things. Not surprisingly, many people give up on prayer when they feel (wrongly) that God is not answering them, and not fulfilling their heartfelt requests. In reality, prayer is something quite different.

A look through the text of Jewish prayers reveals that there is very little requesting at all. The vast majority of the text is made up of verses of praise, gratitude, and acknowledgement. We incessantly thank God for all that He does for us, and describe over and over again His greatness and kindness. It is only after a long time spent in gratitude and praise that we have the Amidah, when we silently request 19 things from God (and can add some extra personal wishes, too). Following this, we go back to praise and gratitude to conclude the prayers.

Many (rightly) ask: what is the point of this repetitive complimenting of God? Does He really need our flattery? The answer is, of course, no, an infinite God does not need any of it. So why do we do it?

One answer is that it is meant to build within us an appreciation of God; to remind us of all the good that He does for us daily, and to shift our mode of thinking into one of being positive and selfless. Through this, we build a stronger bond with God, and remain appreciative of that relationship.

The exact same is true in marriage. Many go into marriage with the mindset of what they can get out of it. They are in a state of always looking to receive from their spouse. Often, even though they do receive a great deal from their partner, they become accustomed to it, and forget all the good that comes out of being married. They stop appreciating each other so, naturally, the marriage stagnates and the couple drifts apart.

Such a mindset must be altered. The dialogue should be like that of prayer: mostly complimenting, acknowledging, and thanking, with only a little bit of request. The Torah tells us that God created marriage so that man is not alone and has a helper by his side. The Torah says helper, not caretaker. We should appreciate every little bit that our spouses do, for without them in our lives we would be totally alone and would not even have that little bit. The Talmud (Yevamot 62a) tells a famous story of Rabbi Chiya, whose wife constantly tormented him and yet, not only did he not divorce her, but he would always bring her the finest goods. His puzzled students questioned him on this, to which he responded: “It is enough that they rear our children and save us from sin.”

A Kind Word

By switching the dialogue to one of positive words and gratitude, we remain both appreciative of the relationship, and aware of how much good we do receive from our other halves. Moreover, such positive words naturally motivate the spouse to want to do more for us, while constant criticism brings about the very opposite result.

Similarly, our Sages teach that when we constantly praise God and speak positively of Him, it naturally stirs up His mercy, and this has the power to avert even the most severe decrees upon us. We specifically quote this from Jeremiah (31:17-19) in our High Holiday prayers:

I have surely heard Ephraim wailing… Ephraim is my precious child; a child of delight, for as soon as I speak of him, I surely remember him still, and My heart yearns for him. I will surely have compassion for Him—thus said Hashem.

Ephraim is one of the Biblical names for the children of Israel, especially referring to the wayward Israelite tribes of northern Israel. Despite the waywardness, Ephraim’s cries to God spark God’s compassion and love for His people.

A kind, endearing word can go very far in prayer, as in marriage. The same page of Talmud cited above continues to say that Rav Yehudah had a horrible wife, too, yet taught his son that a man “who finds a wife, finds happiness”. His son, Rabbi Isaac, questioned him about this, to which Rav Yehudah said that although Isaac’s mother “was indeed irascible, she could be easily appeased with a kindly word.”

Judging the Self

The Hebrew word for prayer l’hitpalel, literally means “to judge one’s self”. Prayer has a much deeper purpose: it is a time to meditate on one’s inner qualities, both positive and negative, and to do what’s sometimes called a cheshbon nefesh, an “accounting of the soul”. Prayer is meant to be an experience of self-discovery. A person should not just ask things of God, but question why they are asking this of God. Do you really need even more money? What would you do with it? Might it actually have negative consequences rather than positive ones? Would you spend it on another nice car, or donate it to a good cause? Why do you need good health? To have the strength for ever more sins, or so that you can fulfill more mitzvot? Do you want children for your own selfish reasons or, like Hannah, to raise tzadikim that will rectify the world and infuse it with more light and holiness?

Prayer is not simply for stating our requests, but analyzing and understanding them. Through proper prayer, we might come to the conclusion that our requests need to be modified, or sometimes annulled entirely. And when finally making a request, it is important to explain clearly why you need that particular thing, and what good will come out of it.

Central to this entire process is personal growth and self-development. In that meditative state, a person should be able to dig deep into their psyche, find their deepest flaws, and resolve to repair them. In the merit of this, God may grant the person’s request. To paraphrase our Sages (Avot 2:4), when we align our will with God’s will, then our wishes become one with His wishes, and our prayers are immediately fulfilled.

Once more, the same is true in marriage. Each partner must constantly judge their performance, and measure how good of a spouse they have been. What am I doing right and what am I doing wrong? Where can I improve? How can I make my spouse’s life easier today? Where can I be more supportive? What exactly do I need from my spouse and why? In the same way that we are meant to align our will with God’s will, we must also align our will with that of our spouse.

The Torah commands that a husband and wife must “cleave unto each other and become one flesh” (Genesis 2:24). The two halves of this one soul must reunite completely. This is what Isaac and Rebecca did, so much so that they even prayed as one. In fact, Isaac and Rebecca were the first to perfectly fulfil God’s command of becoming one, and this is hinted to in the fact that the gematria of “Isaac” (יצחק) and “Rebecca” (רבקה) is 515, equal to “one flesh” (בשר אחד). More amazing still, 515 is also the value of “prayer” (תפלה). The Torah itself makes it clear that marital union and prayer are intertwined.

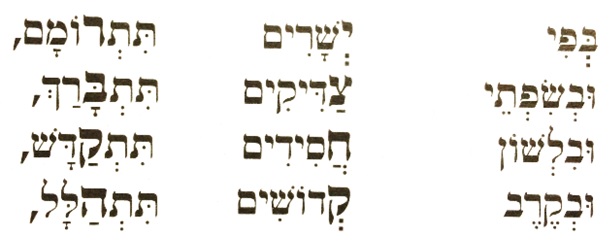

One of the most popular Jewish prayers is “Nishmat Kol Chai”, recited each Shabbat right before the Shema and Amidah. The prayer ends with an acrostic that has the names of Isaac and Rebecca. The names are highlighted to remind us of proper prayer, and that first loving couple which personified it.

Confession

The last major aspect of Jewish prayer is confession. Following the verses of praise and the requests comes vidui, confessing one’s sins and genuinely regretting them. It is important to be honest with ourselves and admit when we are wrong. Among other things, this further instills within us a sense of humility. The Talmud (Sotah 5a) states with regards to a person who has an ego that God declares: “I and he cannot both dwell in the world.” God’s presence cannot be found around a proud person.

In marriage, too, ego has no place. It is of utmost significance to be honest and admit when we make mistakes. It is sometimes said that the three hardest words to utter are “I love you” and “I am sorry”. No matter how hard it might be, these words need to be a regular part of a healthy marriage’s vocabulary.

And more than just saying sorry, confession means being totally open in the relationship. There should not be secrets or surprises. As we say in our prayers, God examines the inner recesses of our hearts, and a couple must likewise know each other’s deepest crevices, for this is what it means to be one. In place of surreptitiousness and cryptic language, there must be a clear channel of communication that is always wide open and free of obstructions.

To summarize, successful prayer requires first and foremost a great deal of positive, praising, grateful language, as does any marriage. Prayer also requires, like marriage, a tremendous amount of self-analysis, self-discovery, and growth. And finally, both prayer and marriage require unfailing honesty, open communication, and forgiveness. In prayer, we make God the centre of our universe. In marriage we make our spouse the centre of our universe. In both, the result is that we ultimately become the centre of their universe, and thus we become, truly, one.