This week’s parasha, Terumah, begins with God’s command to the people to bring their voluntary contributions in support of the construction of the Mishkan, the Holy Tabernacle. One of the oldest Jewish mystical texts, Sefer haBahir, explains that this voluntary “offering of the heart” (as the Torah calls it) refers to prayer, and prayer is how we can fulfil that mitzvah nowadays. Indeed, the root of the term terumah literally means “elevation”, just as we elevate our prayers heavenward.

‘Jew Praying’ by Ilya Repin (1875)

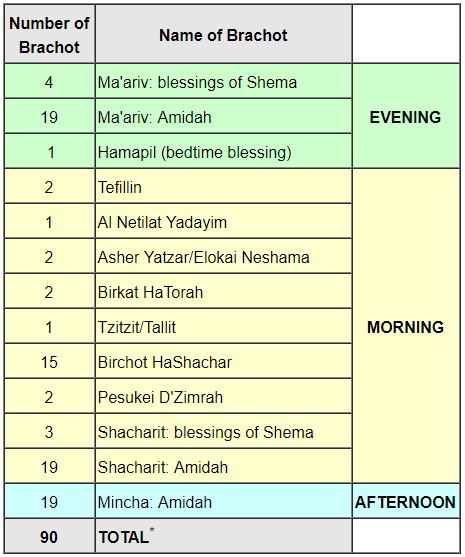

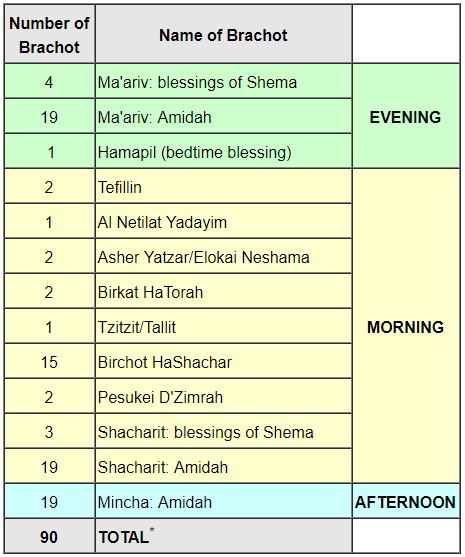

Judaism is known for its abundance of prayer. While Muslims pray five times a day, each of those prayers lasts only a few minutes. Jews may “only” have three daily prayers, yet the morning prayer alone usually takes an hour or so. Besides this, Jews recite berakhot—blessings and words of gratitude to God—on everything they eat, both before and after; on every mitzvah they perform; and even after going to the bathroom. Jewish law encourages a Jew to say a minimum of one hundred blessings a day. This is derived from Deuteronomy 10:12: “And now Israel, what does God ask of you?” The Sages (Menachot 43b) play on these words and say not to read what (מה) does God ask of you, but one hundred (מאה) God asks of you—one hundred blessings a day! The Midrash (Bamidbar Rabbah 18:17) further adds that in the time of King David a plague was sweeping through Israel and one hundred people were dying each day. It was then that David and his Sanhedrin instituted the recital of one hundred daily blessings, and the plague quickly ceased.

Of course, God does not need our blessings at all. By reciting so many blessings, we are constantly practicing our gratitude and recognizing how much goodness we truly receive. This puts us in a positive mental state throughout the day. The Zohar (I, 76b, Sitrei Torah) gives a further mystical reason for these blessings: when a person goes to sleep, his soul ascends to Heaven. Upon returning in the morning, the soul is told “lech lecha—go forth for yourself” (the command God initially gave to Abraham) and it is given one hundred blessings to carry it through the day. There is a beautiful gematria here, for the value of lech lecha (לך לך) is 100. Thus, a person who recites one hundred blessings a day is only realizing the blessings he was already given from Heaven, and extracting them out of their potential into actual benefit.

Not surprisingly then, a Jew starts his day with a whole host of blessings. The morning prayer (Shacharit) itself contains some 47 blessings. Within a couple of hours of rising, one has already fulfilled nearly half of their daily quota, and is off to a great start for a terrific day.

(Courtesy: Aish.com) If one prays all three daily prayers, they will already have recited some 90 blessings. As such, it becomes really easy to reach 100 blessings in the course of a day, especially when adding blessings on food and others.

Having said that, is it absolutely necessary to pray three times a day? Why do we pray at all, and what is the origin of Jewish prayer? And perhaps most importantly, what should we be praying for?

Where Does Prayer Come From?

The word tefilah (“prayer”) appears at least twenty times in the Tanakh. We see our forefathers praying to God on various occasions. Yet, there is no explicit mitzvah in the Torah to pray. The Sages derive the mitzvah of prayer from Exodus 23:25: “And you shall serve [v’avad’tem] Hashem, your God, and I will bless your food and your drink, and I will remove illness from your midst.” The term avad’tem (“worship”, “work”, or “service”) is said to refer to the “service of the heart”, ie. prayer. This verse fits neatly with what was said earlier: that prayer is not about serving God, who truly requires no service, but really about receiving blessing, as God says He will bless us and heal us when we “serve” Him.

So, we have the mitzvah of prayer, but why three times a day? The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204) clearly explains the development of prayer in his Mishneh Torah (Chapter 1 of Hilkhot Tefillah and Birkat Kohanim in Sefer Ahava):

It is a positive Torah commandment to pray every day, as [Exodus 23:25] states: “You shall serve Hashem, your God…” Tradition teaches us that this service is prayer, as [Deuteronomy 11:13] states: “And serve Him with all your heart”, and our Sages said: “Which is the service of the heart? This is prayer.” The number of prayers is not prescribed in the Torah, nor does it prescribe a specific formula for prayer. Also, according to Torah law, there are no fixed times for prayers.

… this commandment obligates each person to offer supplication and prayer every day and utter praises of the Holy One, blessed be He; then petition for all his needs with requests and supplications; and finally, give praise and thanks to God for the goodness that He has bestowed upon him; each one according to his own ability.

A person who was eloquent would offer many prayers and requests. [Conversely,] a person who was inarticulate would speak as well as he could and whenever he desired. Similarly, the number of prayers was dependent on each person’s ability. Some would pray once daily; others, several times. Everyone would pray facing the Holy Temple, wherever he might be. This was the ongoing practice from [the time of] Moshe Rabbeinu until Ezra.

The Rambam explains that the mitzvah to pray from the Torah means praising God, asking Him to fulfil one’s wishes, and thanking Him. No specific text is needed, and once a day suffices. This is the basic obligation of a Jew, if one wants simply to fulfil the direct command from the Torah. The Rambam goes on to explain why things changed at the time of Ezra (at the start of the Second Temple era):

When Israel was exiled in the time of the wicked Nebuchadnezzar, they became interspersed in Persia and Greece and other nations. Children were born to them in these foreign countries and those children’s language was confused. The speech of each and every one was a concoction of many tongues. No one was able to express himself coherently in any one language, but rather in a mixture [of languages], as [Nehemiah 13:24] states: “And their children spoke half in Ashdodit and did not know how to speak the Jewish language. Rather, [they would speak] according to the language of various other peoples.”

Consequently, when someone would pray, he would be limited in his ability to request his needs or to praise the Holy One, blessed be He, in Hebrew, unless other languages were mixed in with it. When Ezra and his court saw this, they established eighteen blessings in sequence [the Amidah].

The first three [blessings] are praises of God and the last three are thanksgiving. The intermediate [blessings] contain requests for all those things that serve as general categories for the desires of each and every person and the needs of the whole community.

Thus, the prayers could be set in the mouths of everyone. They could learn them quickly and the prayers of those unable to express themselves would be as complete as the prayers of the most eloquent. It was because of this matter that they established all the blessings and prayers so that they would be ordered in the mouths of all Israel, so that each blessing would be set in the mouth of each person unable to express himself.

‘Prayer of the Killed’ by Bronisław Linke

The generation of Ezra and the Great Assembly approximately two and a half millennia ago composed the fixed Amidah (or Shemoneh Esrei) prayer of eighteen blessings. This standardized prayer, and ensured that people were praying for the right things, with the right words. (Of course, one is allowed to add any additional praises and supplications they wish, and in any language.)

Reciting the Amidah alone technically fulfils the mitzvah of prayer, whereas the additional passages that we read (mostly Psalms) were instituted by later Sages in order to bring one to the right state of mind for prayer. (Note that the recitation of the Shema is a totally independent mitzvah, although it is found within the text of prayer. The only other Torah-mandated prayer mitzvah is reciting birkat hamazon, the grace after meals.) The Rambam continues to explain why three daily prayers were necessary:

They also decreed that the number of prayers correspond to the number of sacrifices, i.e. two prayers every day, corresponding to the two daily sacrifices. On any day that an additional sacrifice [was offered], they instituted a third prayer, corresponding to the additional offering.

The prayer that corresponds to the daily morning sacrifice is called the Shacharit prayer. The prayer that corresponds to the daily sacrifice offered in the afternoon is called the Minchah prayer and the prayer corresponding to the additional offerings is called the Musaf prayer.

They also instituted a prayer to be recited at night, since the limbs of the daily afternoon offering could be burnt the whole night, as [Leviticus 6:2] states: “The burnt offering [shall remain on the altar hearth all night until morning].” In this vein, [Psalms 55:18] states: “In the evening, morning, and afternoon I will speak and cry aloud, and He will hear my voice.”

The Arvit [evening prayer] is not obligatory like Shacharit and Minchah. Nevertheless, the Jewish people in all the places that they have settled are accustomed to recite the evening prayer and have accepted it upon themselves as an obligatory prayer.

Since customs that are well-established and accepted by all Jewish communities become binding, a Jew should ideally pray three times daily. The Rambam goes on to state that one may pray more times if they so desire, but not less. We see a proof-text from Psalms 55:18, where King David clearly states that he prays “evening, morning, and afternoon”. Similarly, we read of the prophet Daniel that

he went into his house—with his windows open in his upper chamber toward Jerusalem—and he kneeled upon his knees three times a day, and prayed, and gave thanks before his God, as he had always done. (Daniel 11:6)

The Tanakh also explains why prayer was instituted in the place of sacrifices. The prophet Hoshea (14:3) stated that, especially in lieu of the Temple, “we pay the cows with our lips”. King David, too, expressed this sentiment (Psalms 51:17-18): “My Lord, open my lips and my mouth shall declare Your praise. For You have no delight in sacrifice, else I would give it; You have no pleasure in burnt-offerings.” This verse is one of many that shows God does not need animal sacrifices at all, and the Torah’s commands to do so were only temporary, as discussed in the past. It was always God’s intention for us to “serve” Him not through sacrifices, but through prayers. (See also Psalms 69:31-32, 141:2, and Jeremiah 7:21-23.)

The Mystical Meaning of Prayer

While the Sages instruct us to pray at regular times of the day, they also caution that one should not make their prayers “fixed” or routine (Avot 2:13). This apparent contradiction really means that one’s prayer should be heartfelt, genuine, and not recited mechanically by rote. One should have full kavanah, meaning the right mindset and complete concentration. The Arizal (and other Kabbalists) laid down many kavanot for prayer, with specific things to have in mind—often complex formulas of God’s Names or arrangements of Hebrew letters, and sometimes simple ideas to think of while reciting certain words.

The Arizal explained (in the introduction to Sha’ar HaMitzvot) that one should not pray only because they need something from God. Rather, prayer is meant to remind us that God is the source of all blessing and goodness (as discussed above) and reminds us that only the Infinite God can provide us with everything we need. By asking things of God, we ultimately to draw closer to Him, like a child to a parent. There is also a much deeper, more mystical reason for prayer. Praying serves to elevate sparks of holiness—and possibly even whole souls—that are trapped within kelipot, spiritual “husks” (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, ch. 39). Prayer is part of the long and difficult process of tikkun, rectifying Creation and returning it to its perfect primordial state.

The Zohar (II, 215b) further states that there are four tikkunim in prayer: tikkun of the self, tikkun of the lower or physical world, tikkun of the higher spiritual worlds, and the tikkun of God’s Name. Elsewhere (I, 182b), the Zohar explains that man is judged by the Heavens three times daily, corresponding to the three prayer times. This fits well with the famous Talmudic statement (Rosh Hashanah 16b) that prayer is one of five things that can change a person’s fate, and annul any negative decrees that may be upon them. (The other four are charity, repentance, changing one’s name, or moving to a new home.)

I once heard a beautiful teaching in the name of the Belzer Rebbe that ties up much of what has been discussed so far:

According to tradition, Abraham was first to pray Shacharit, as we learn from the fact that he arose early in the morning for the Akedah (Genesis 22:3, also 19:27, 21:14). Isaac instituted Minchah, as we read how he went “to meditate in the field before evening” (Genesis 24:63). Jacob instituted the evening prayer, as we learn from his nighttime vision at Beit El (Genesis 28).

Each of these prayers was part of a cosmic tikkun, the rebuilding of the Heavenly Palace (or alternatively, the building of Yeshiva shel Ma’alah, the Heavenly Study Hall). God Himself began the process, and raised the first “wall” in Heaven with his camp of angels. This is the “camp of God” (מחנה) that Jacob saw (Genesis 32:3). Abraham came next and built the second “wall” in Heaven through his morning prayer on the holy mountain (הר) of Moriah (Genesis 22:14). Then came Isaac and built the third Heavenly wall when he “meditated in the field” (שדה). Jacob erected the last wall and finally saw a “House of God” (בית). Finally, Moses completed the structure by putting up a roof when he prayed Va’etchanan (ואתחנן). These terms follow an amazing numerical pattern: מחנה is 103, הר is 206 (with the extra kollel)*, שדה is 309, בית is 412, and ואתחנן is 515. Each prayer (and “wall”) of the forefathers is a progressive multiple of 103 (God’s wall).

We can learn a great deal from this. First, that prayer helps to build our “spiritual home” in Heaven. Second, that prayer both maintains the “walls” of God’s Palace in Heaven, and broadens His revealed presence on this Earth. And finally, that prayers are much more than praises and requests, they are part of a great cosmic process of rectification.

What Should We Pray For?

Aside from the things we request in the Amidah and other prayers, and aside from the all mystical kavanot we should have in mind, what else should we ask for in our personal prayers? A person can ask God of anything that they wish, of course. However, if they want their prayers answered, our Sages teach that it is better to prayer not for one’s self, but for the needs of others. We learn this from the incident of Abraham and Avimelech (Genesis 20). Here, God explicitly tells Avimelech that when Abraham prays for him, he will be healed. After the Torah tells us that Abraham prayed for Avimelech and his household was indeed healed, the very next verse is that “God remembered Sarah” and continues with the narrative of Isaac’s birth. Thus, we see how as soon as Abraham prayed for Avimelech’s household to be able to give birth to children, Abraham himself finally had a long-awaited child with Sarah.

Speaking of children, the Talmud advices what a person should pray for during pregnancy (Berakhot 60a). In the first three days after intercourse, one should pray for conception. In the first forty days of pregnancy, one can pray for which gender they would like the child to be, while another opinion (54a) holds that one shouldn’t pray for this and leave it up to God. (Amazingly, although gender is determined by chromosomes upon conception, we know today that gender development actually begins around day 42 of gestation. So, just as the Talmud states, there really is no point in hoping for a miraculous change in gender past day 40.) Henceforth in the first trimester, one should pray that there shouldn’t be a miscarriage. In the second trimester, one should pray that the child should not be stillborn, God forbid. In the final trimester, one should pray for an easy delivery.

Lastly, in addition to common things that everyone prays for (peace, prosperity, health, etc.) the Talmud states that there are three more things to pray for: a good king, a good year, and a good dream (Berakhot 55a). The simple meaning here is to pray that the government won’t oppress us, that only good things will happen in the coming year, and that we will be able to sleep well without stresses and worries. Rav Yitzchak Ginsburgh points out that a good king (מלך) starts with the letter mem; a good year with shin (שנה); and good dream (חלום) with chet. This spells the root of Mashiach, for it is only when Mashiach comes that we will finally have a really good king, a really good year, and have the most peaceful sleep, as if we are living in a good dream.

Courtesy: Temple Institute

*Occasionally, gematria allows the use of a kollel, adding one to the total. There are several reasons for doing this, and the validity of the practice is based on Genesis 48:5. Here, Jacob says that Ephraim and Menashe will be equal to Reuben and Shimon. The gematria of “Ephraim and Menashe” (אפרים ומנשה) is 732, while the gematria of “Reuben and Shimon” (ראובן ושמעון) is 731. Since Jacob himself said they are equal, that means we can equate gematriot that are one number away from each other!

For those who don’t like kollels and want exact numbers (as I do), we can present another solution: Abraham’s prayer is the only one not exactly a multiple of God’s original “wall” of 103. The reason that one wall is “incomplete”, so to speak, is because every house needs an opening—Abraham’s wall is the one with the door, so his wall is a tiny bit smaller!

The Zohar goes on to interpret the laws in the Torah with regards to the mechanisms of reincarnation. For example, whereas the Torah begins by describing a Hebrew servant who is indentured for six years of labour and must then be freed in the seventh year, the Zohar interprets that this is really speaking of souls which must reincarnate in order to repair the six middot before they could be freed. (The middot are the primary character traits: chessed, kindness; gevurah, restraint; tiferet, balance and truth; netzach, persistence and faith; hod, gratitude and humility; and yesod, sexual purity.)

The Zohar goes on to interpret the laws in the Torah with regards to the mechanisms of reincarnation. For example, whereas the Torah begins by describing a Hebrew servant who is indentured for six years of labour and must then be freed in the seventh year, the Zohar interprets that this is really speaking of souls which must reincarnate in order to repair the six middot before they could be freed. (The middot are the primary character traits: chessed, kindness; gevurah, restraint; tiferet, balance and truth; netzach, persistence and faith; hod, gratitude and humility; and yesod, sexual purity.)