How do we know that Rosh Hashanah is really the new year for the world? And how do we know it is a judgement day if the Torah seemingly doesn’t say so? Find out in this class! Also discussed is the geographical location of the Garden of Eden, the identity of the Forbidden Fruit, the nature of Satan, and how the current generation is a return of the generation of the Exodus, as well as the connections between ancient Egypt and the modern world.

Tag Archives: Judgement Day

Mashiach and the Mysterious 13th Zodiac Sign

When Jacob blesses his children before his passing, he begins by telling his sons that he wishes to reveal to them what will happen b’acharit hayamim, “in the End of Days”. Yet, the text we read does not appear to say anything about the End of Days! The Talmud (Pesachim 56a) states that the Shekhinah withdrew from Jacob at that moment so he was unable to reveal those secrets. If that’s the case, how was he able to properly bless his children?

The Talmud states that when the Shekhinah left him, Jacob worried one of his children was unworthy to hear those secrets. His sons then recited the Shema in unison and said, “just as there is only One in your heart, so is there in our heart only One.” Jacob was comforted to know they are all indeed righteous, and it seems the Shekhinah returned to him at this point, allowing him to bless his children in holiness. Nonetheless, Jacob reasoned that to reveal the secret of the End in explicit fashion would be unwise, so he encoded these mysteries within the blessings he recited. In fact, Jacob not only encrypted what will happen in the End, but summarized the breadth of Jewish history (see ‘How Jacob Prophesied All of Jewish History’ in Volume One of Garments of Light).

One place where Jacob appears to make an explicit reference to the End is in blessing Dan, when he says, “I hope for Your salvation, Hashem” (Genesis 49:18). Jacob says Dan will be the one to judge his people—alluding to the great Judgement Day—and wage the final battles like a “snake upon the road… who bites the horse’s heel so that its rider falls backwards”. Jacob is speaking of Mashiach. Although Mashiach is a descendent of David and from the tribe of Judah, the Midrash states that this is only through his father, while through his mother’s lineage Mashiach hails from the tribe of Dan.

Why does Jacob compare Mashiach to a snake?

Snakes of Divination

In cultures around the world, there is a peculiar connection between snakes and prophecy. In ancient Greece, for example, the Oracle went into a prophetic trance when supposedly breathing in the fumes (or spirit) of the dead python upon which the Temple in Delphi was built. According to myth, this great python (a word which has a Hebrew equivalent in the Tanakh, פתן) was slain by Apollo. The Temple was built upon its carcass. For this reason, the Greek prophetess was known as Pythia.

Similarly, the Romans had their sacred hill on the Vatican (later adopted as the centre of Christianity). The second-century Latin author Aulus Gellius explained that the root of the word Vatican is vates, Latin for “prophet”. Others explain that vatican refers more specifically to a “divining serpent”. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world the Aztecs had Quetzalcoatl and the Mayans had Kukulkan, the “feathered serpent” god of wisdom and learning. And such mystical dragons appear just about everywhere else, from Scandinavia to China.

Incredibly, the Torah makes the same connection, where Joseph is described as a diviner who uses a special goblet to nachesh inachesh (Genesis 44:5). This term for divination is identical to nachash, “snake”. In Modern Hebrew, too, the term for guessing or predicting is lenachesh. Why is the snake associated with otherworldly wisdom and prophecy?

Primordial Serpent

Back in the Garden of Eden, it was the Nachash, “Serpent”, who encouraged Eve to consume of the Forbidden Fruit. This was the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The Serpent is the one who unlocked the minds of Adam and Eve to higher wisdom so that they could “be like God”. Jewish tradition maintains that Adam and Eve were eventually supposed to eat of the Tree of Knowledge (for otherwise why would God put it there to begin with?) but they simply rushed to do so when they were not yet ready. They transgressed God’s command, and knew not what to do with all of this tremendous information, resulting in the shameful descent of man into sin. The one who instigated it all was the Nachash.

It appears that ever since then, the snake has been a symbol of forbidden wisdom. Such divination and mysticism can be quite dangerous, and most are unable to either grasp or properly use this knowledge. The Talmud cautions as much in its famous story of the four sages who entered “Pardes” (Chagigah 14b). Pardes is an acronym for the depths of Jewish wisdom, from the simple (pshat) and sub-textual (remez) to the metaphorical (drash) and esoteric (sod). The result of entering the mystical dimensions was that Ben Azzai died, Ben Zoma detached from this world, and Elisha ben Avuya became a heretic. Only Rabbi Akiva was able to “enter in peace and depart in peace.” It is important to remember that Rabbi Akiva was the teacher of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, the originator of the Zohar. (Still, the Zohar, like most mystical texts, does not speak explicitly of esoteric matters, but cloaks them in layers of garments and complex language which only the most astute can unravel.)

Long before, Joseph was a master of this wisdom, surprising even the Pharaoh and his best mystics, who proclaimed: “Can there be such a man in whom the spirit of God rests?” (Genesis 41:38). Joseph, of course, is a prototype of Mashiach. The sages state that Mashiach is a great prophet and sage in his own right, but can he really surpass the unparalleled prophecy of Moses or the wisdom of Solomon? The Alter Rebbe (Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, 1745-1812) solved the issue thus:

After the resurrection all will rise… the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, Moses and Aaron, all the righteous ones and the prophets, tens of thousands beyond number. Is it possible that Mashiach will teach them the same Torah that is revealed to us today? …Will all who knew the whole Torah be required to learn new laws from Mashiach? We must therefore say that Mashiach will instruct them in the “good of discernment and knowledge of the secrets of the esoteric teachings of Torah” that the “eyes will not have seen”—Moses and the Patriarchs not having been privileged to that knowledge, for only to Mashiach will it be revealed as it is written of him [Isaiah 52:13] “and he shall be very high.” (Likkutei Torah, Tzav)

Mashiach is the greatest of mystics, the holder of “forbidden” knowledge which will soon no longer be forbidden. The time will come when, as God originally intended, man will eat from the Tree of Knowledge and be “like God”. That first requires a return of mankind to the Garden of Eden, which is the very task of Mashiach. Beautifully, the gematria of Mashiach (משיח)—the one who brings us back into Eden—is 358, the same as Nachash (נחש)—the one who forced us out to begin with. And so, as Jacob foresaw, the snake symbolizes Mashiach himself.

While Mashiach is likened to a serpent, he must also defeat the Primordial Serpent which embodies all evil. Indeed, the Sages speak of two serpents (based on Isaiah 27:1): the “straight” serpent (nachash bariach) and the “twisted” serpent (nachash ‘akalaton). Mashiach is the straight serpent that devours the twisted one. This was all alluded to in Moses’ staff-turned-serpent consuming the Pharaoh’s staff-turned-serpent. In fact, another serpent staff, the nachash nechoshet, is later used by Moses to heal the nation. This healing staff found its way into Greek myth as well, where it was wielded by the healer god Asclepius, and eventually into the modern internationally-recognized medical symbol.

While Mashiach is likened to a serpent, he must also defeat the Primordial Serpent which embodies all evil. Indeed, the Sages speak of two serpents (based on Isaiah 27:1): the “straight” serpent (nachash bariach) and the “twisted” serpent (nachash ‘akalaton). Mashiach is the straight serpent that devours the twisted one. This was all alluded to in Moses’ staff-turned-serpent consuming the Pharaoh’s staff-turned-serpent. In fact, another serpent staff, the nachash nechoshet, is later used by Moses to heal the nation. This healing staff found its way into Greek myth as well, where it was wielded by the healer god Asclepius, and eventually into the modern internationally-recognized medical symbol.

And that brings us back to the End of Days.

The 13th Zodiac

In recent years, there have been whispers of a necessity to change the current 12-sign horoscope to include a 13th zodiac sign. This was featured in the media on a number of occasions, with flashy headlines suggesting that some people’s astrological sign may now have changed. It is based on the fact that there is a “precession of the equinoxes”: Earth’s axis changes very slowly over time, meaning that the constellations which are visible in the night sky change, too.

The astrological signs are based on the 12 major constellations (out of 88 constellations total) that align with the sun and “rule” for about a month’s time every year (each making up 30º of the total 360º). The argument is that due to the precession of the equinoxes, a 13th sign has crept in which we can no longer ignore. The majority of astrologers have rejected this argument, mainly because astrology isn’t really based on the stars but fixed to the vernal equinox. While some in the East (namely Hindus) use “sidereal astrology”, which is based on shifting star positions, the system used in the West (“tropical astrology”) has 12 signs roughly corresponding to the 12 months.

The same is true in traditional Jewish thought, where each sign corresponds to a month on the Hebrew calendar, as well as to one of the twelve tribes of Israel. Having said that, including a 13th month for the Jewish system is not a problem at all. In fact, it is actually a solution, since the Jewish calendar has a 13th month in a leap year. The extra month has an astrological sign, too! Similarly, although we always speak of twelve tribes of Israel, there are really thirteen since, as we read in this week’s parasha, Jacob made Joseph count as two separate tribes: Ephraim and Menashe.

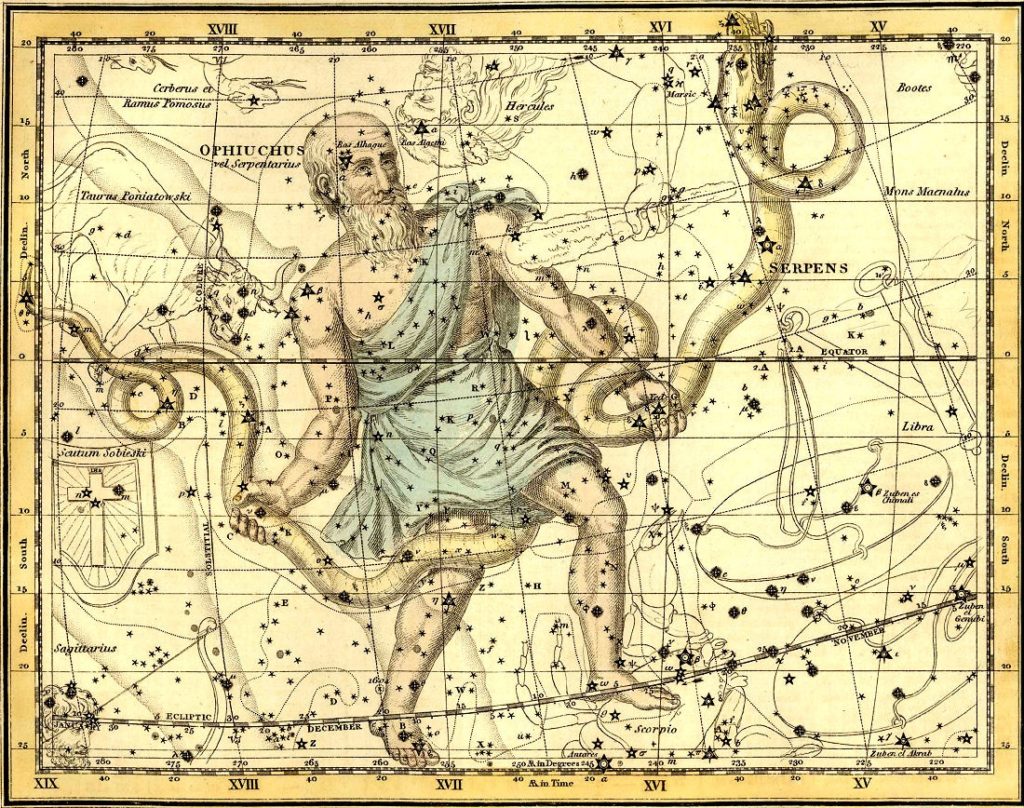

Whatever the case, whether the horoscope requires modification or not is irrelevant to Judaism, which denies any astrological effect on Israel (see ‘Should Jews Believe in Astrology’ in Volume One of Garments of Light). Besides, unlike astrologers, astronomers both ancient and modern have always been aware of this thirteenth constellation. To the ancient Babylonians it was the snake-like Nirah, while to the ancient Greeks it was known as Ophiuchus, the “serpent-bearer”. This constellation is in the shape of a man firmly grasping a twisted snake (the interlinked constellation Serpens). This is, of course, the very symbol of Mashiach, that serpentine saviour who defeats the primordial snake and all of its evil. After being an astrological footnote for a very long time, Ophiuchus has entered the spotlight, as if the cosmos itself is reminding us of Mashiach’s impending arrival.

The constellation Ophiuchus (or Serpentarius) grasping the constellation Serpens, from Alexander Jamieson’s Celestial Atlas of 1822. It is interesting to note that Mashiach must be a direct descendant of King David, whose own father Yishai (Jesse) was also called Nachash! (See Talmud, Shabbat 55b.)

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!

Secrets of Rosh Hashanah

This first of this week’s two Torah portions, Nitzavim, is always read right before Rosh Hashanah, and appropriately begins: “You are all standing today before Hashem, your God…” The verse has traditionally been seen as an allusion to Rosh Hashanah, when each person stands before God and is judged. The Torah says today, implying one day, yet everyone celebrates Rosh Hashanah over two days. This is true even in Israel, where yom tovs are typically observed for only one day.

This first of this week’s two Torah portions, Nitzavim, is always read right before Rosh Hashanah, and appropriately begins: “You are all standing today before Hashem, your God…” The verse has traditionally been seen as an allusion to Rosh Hashanah, when each person stands before God and is judged. The Torah says today, implying one day, yet everyone celebrates Rosh Hashanah over two days. This is true even in Israel, where yom tovs are typically observed for only one day.

The reason for this is because in ancient times there was no set calendar, so a new month was declared based on the testimony of two witnesses. Once the new month was declared in Jerusalem, messengers were sent out to inform the rest of the communities in the Holy Land, and beyond. Communities that were far from Israel would not receive the message until two or three weeks later, so they would often have to observe the holidays based on their own (doubtful) opinion of when the holiday should be. They therefore kept each yom tov for two days.

Rosh Hashanah, however, is the only holiday that takes place on the very first day of the month, so as soon as the new month of Tishrei was declared, it was immediately Rosh Hashanah, and messengers could not be sent out! Thus, even communities across Israel would observe the holiday for two days, based on their own observations.

Although today we have a set calendar, and there is no longer a declaration of a new month based on witnesses, two days are still observed since established traditions become permanent laws. Of course, this is only the simplest of explanations, for there are certainly deeper reasons in observing two days, especially when it comes to Rosh Hashanah.

Judgement in Eden

Rosh Hashanah commemorates the day that God fashioned Adam and Eve. On that same day, the first couple consumed the Forbidden Fruit, were judged, and banished from the Garden of Eden. Originally, they had been made immortal. Now, they had brought death into the world, and God decreed that their earthly life would have an end. Adam and Eve were, not surprisingly, the first people to be inscribed in the Book of Death. Each year since, on the anniversary of man’s creation and judgement, every single human being (Jewish or not) is judged in the Heavenly Court, and inscribed in the Book of Life, or the Book of Death.

This is the idea behind the symbolic consumption of apples in honey. In Jewish tradition, the Garden of Eden is likened to an apple orchard, with the scent of the air in Eden being like that of apples. (Having said that, it is not a Jewish tradition that the Forbidden Fruit itself was an apple!) The apple reminds us of the Garden—of Adam and Eve and their judgement—and we dip it in honey so that our judgement should be sweet.

But what happens when Rosh Hashanah falls on Shabbat? It is well-known that there is no judgement on Shabbat. The Heavenly Court rests, and even the souls in Gehinnom are said to have a day off. This is illustrated by a famous exchange in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 65b) between Rabbi Akiva and the Roman governor of Judea at the time, Turnus Rufus:

Turnus Rufus asked Rabbi Akiva: “How does [Shabbat] differ from any other day?”

He replied: “How does one official differ from another?”

“Because my lord [the Roman Emperor], wishes it so.”

Rabbi Akiva said: “the Sabbath, too, is distinguished because the Lord wishes it so.”

He asked: “How do you know that this day is the Sabbath?”

[Rabbi Akiva] answered: “The River Sambation proves it; the ba’al ov proves it; your father’s grave proves it, as no smoke ascends from it on Shabbat.”

An illustration of Rabbi Akiva from the Mantua Haggadah of 1568

Rufus asks Rabbi Akiva how the Jews are certain that the Sabbath that they keep is actually the correct seventh day since Creation. Rabbi Akiva brings three proofs:

The first is a legendary river called the Sambation (or Sabbation), which was known in those days, and which raged the entire week, but flowed calmly only on Shabbat. The second proof is that people who summon the dead from the afterlife (practicing a form of witchcraft called ov) are unable to channel the dead on Shabbat. (I know of a person who was once involved in such dark arts and became a religious Jew after realizing that he was never able to summon spirits on the Sabbath or on Jewish holidays!) Lastly, Rabbi Akiva notes how Turnus Rufus’ own father’s grave would emit smoke every day of the week, except on Shabbat. This is because the soul of Rufus’ wicked father was in Gehinnom, but all souls in that purgatory get a reprieve on Shabbat. (Historical sources suggest that Rufus’ father was Terentius Rufus, one of the generals involved in the destruction of the Second Temple.)

Based on this, we can understand why Rosh Hashanah must be observed over two days. When the holiday falls on Shabbat, no judgement can take place, so the judgement is pushed off to the next day. This is also related to the fact that when Rosh Hashanah falls on Shabbat, the shofar is not blown. This is not at all because blowing a shofar is forbidden on Shabbat, which is, in fact, permitted.

The simple explanation given for this is that we’re worried the person blowing the shofar might carry it to the synagogue (in a place without an eruv), and carrying is forbidden on Shabbat. The deeper reason is this: Blowing the shofar is supposed to “confound Satan”. Satan is not the trident-carrying, horned demon of the underworld (as popularly believed in Christianity). Rather, Satan literally means the “one who opposes” or the “prosecutor”. It is Satan’s job to serve as the prosecution in the Heavenly Court. The shofar’s blow confuses Satan, and prevents him from working too much against us. On Shabbat, the Heavenly Court rests, and Satan is having a day off, so there is no need to confound him!

The First Shabbat

One might argue that Rosh Hashanah should only be two days long when it falls on Shabbat; in other years, one day would suffice. Other than the fact that this would be confusing—as the holiday would span different lengths in different years—there are other explanations for the two days, including that each day involves different types of judgement (for example, one day for sins bein adam l’Makom, between man and God; and one day for bein adam l’havero, between man and his fellow). Nonetheless, our Sages still describe Rosh Hashanah as really being one day—one unique, extra-long, 48-hour day which our Sages called yoma arichta, literally the “long day”. Perhaps this is another reason for the custom of not sleeping on the “first night” of Rosh Hashanah. (The other reason: how could anyone possibly sleep through their own trial?)

Finally, the story of Rabbi Akiva and Turnus Rufus gives us one more reason to commemorate Rosh Hashanah over two days. Rufus questioned Rabbi Akiva on how he can be so sure that the Sabbath which he keeps is indeed the correct seventh day going back to Creation. If Rosh Hashanah is the day Adam and Eve were created, then it corresponds to the sixth day of Creation. That means the very next day was the seventh day of Creation, and that the second day of Rosh Hashanah always commemorates the very first Sabbath. When we celebrate on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, we mark Adam and Eve’s first Shabbat, and recognize that each seventh day has been observed ever since, and will continue to be observed for another, 5778th upcoming year.

Shana Tova u’Metuka!