In this week’s parasha, Re’eh, a unique term appears a whopping five times: l’shakhen shmo sham, a place where God will choose “to rest His Name there”. Outside of this parasha, the term only appears once in the rest of the Tanakh. It refers to the only place where Jews are allowed to bring any sacrifices to Hashem (Deuteronomy 12:11), and where Jews should pilgrimage on the major holidays to “rejoice before God” (Deuteronomy 16:11). Although the Chumash doesn’t explicitly say where this place is, it is of course referring to Jerusalem, as we learn later in the Tanakh (for example, I Kings 11:13).

“Pilgrimage to the Second Jerusalem Temple” by Alex Levin

Why doesn’t the Chumash itself name Jerusalem? This is because the Israelites were still in the Wilderness at the time, and at that point they brought their sacrifices in the mobile Mishkan, or “Tabernacle”. In the Wilderness, the Mishkan was the place where God’s Presence rested. Even when the Israelites entered the Holy Land, it took many years for them to reconquer and settle all of it, so the Mishkan remained mobile. The Talmud (Zevachim 118b) lists all the places where the Mishkan was parked:

After 39 years in the Wilderness (since the Mishkan was built and inaugurated a year after the Exodus), it was in Gilgal for 14 years. Half of that time was spent conquering and half dividing up the land among the Tribes. The Mishkan was then placed in Shiloh and remained there for 369 years. However, there was no king in Israel then, and no leader arose to build a permanent Temple. The Talmud states that when Eli the Priest died, Shiloh was destroyed so the Mishkan was moved to the town of Nov. Later in the Tanakh we read how Nov, too, was destroyed, so the Mishkan was moved to Gibeon. When David became king he first reigned for seven years from Hebron. After that, he acquired Jerusalem and brought the Mishkan there. Henceforth, Jerusalem became the seat of the Davidic dynasty, and the place where God’s Name would rest forever.

What makes Jerusalem so special?

Centre of the Universe

Jerusalem’s Temple was built atop Mount Moriah, and the Holy of Holies over a special stone. The Talmud (Yoma 54b) states that this stone, even shetiyah, the Foundation Stone, is literally the point from which God created the universe. The Sages find proof in Psalms 50:1-2, which states: “God spoke and called the Earth, from the rise of the sun until it sets, out of Zion all beauty God shone forth.” That initial burst of light in Creation was at this very point atop Jerusalem.

The word “Zion” itself implies a foundation of sorts. In the Tanakh, we read how the Jebusites built a massive fortress there, metzudat tzion, which the Sages say means an “outstanding fortress”, one with such strong foundations that none could conquer it. Until King David, that is. The Jebusites scoffed at David when he approached with his armies, thinking that their fortress was unconquerable. David proved them wrong, then renamed the fortress after himself, and called the city ‘Ir David, “City of David” (see II Samuel 5).

Long before it was known as City of David, or Zion, and before it was settled by Jebusites, it was already famous as a holy mountain. Upon it, various priests would come to offer incense. This is where the name Moriah comes from, literally mor, “myrrh” (or “incense”), and Yah, “God”. The first priest active there was Melchizedek, identified with Shem, the son of Noah. The Torah calls him a “priest of God, the Most High” and introduces him as the “king of Shalem” (Genesis 14:18). The Book of Jubilees tells us how Noah divided up the Earth among his three sons, and Shem received all the holy places, including Zion (Jubilees 8:19).

Shem built his home on Zion, and called it Shalem, a place that was “wholesome” and “peaceful”. Later on, God commanded Abraham to take Isaac upon Mt. Moriah. At the end of that episode, we read how Abraham called the place Hashem Yireh, since this is the place where “God is seen” (Genesis 22:14). The Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 56:10) states that this holy site now had two names: Yireh and Shalem. Each of these names was given by a holy man, so which would stick? In order not to favour one holy man over another, the two were combined to create Yerushalem, or Yerushalayim, “Jerusalem”.

Jerusalem, Zion, City of David, Moriah, Shalem, Yireh—all are names for this holy place, each signifying something of its incredible past. Indeed, it is said that Jerusalem has seventy different names, just like God, the Jewish people, and the land of Israel, and just as the Torah has seventy different faces. Whatever the case, it is the city that “brings everyone together” (Psalm 122:3) and has the power to “make all Israel friends” (Yerushalmi Chagigah 3:6).

Gate to Heaven

The Midrash states that Zion is the place through which all the blessings from Heaven enter this world, and the place through which all blessings descend upon the Jewish people (Yalkut Shimoni, Ezekiel 392). At the same time, it is the place through which all of our prayers ascend to Heaven, too. This is why Jews always pray towards Jerusalem. And if they are in Jerusalem they pray towards the place where the Holy of Holies stood.

More amazing still, some say that Mt. Moriah is the peak upon which God gave Israel the Torah! In other words, Moriah is one and the same as Sinai. The Midrash (Shocher Tov 68) states that God took off a chunk of Moriah (like a piece of challah) and transplanted it to the Sinai wilderness. After He gave the Torah, He put that chunk back in Jerusalem. This is why the Talmud (Ta’anit 16a, with Tosfot) states it is called Moriah, from root hora’ah, “instruction”, the same as the root of Torah. On Mt. Moriah the Torah was given! And from here, the “fear” or “awe” (mora) of God entered the world.

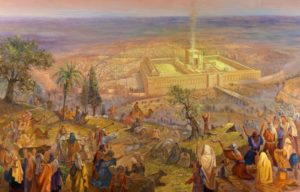

“Jacob’s Ladder” by Stemler and Cleveland (1925)

There is a further allusion to this in that the gematria of Sinai (סיני) is 130, equal to sulam (סלם), “ladder”, referring to the Heavenly Ladder that Jacob envisioned (Genesis 28:12). This vision also took place upon Mt. Moriah. Afterwards, Jacob called the place Beit El, “House of God”, for he had foreseen that the Holy Temple would be built there. Jerusalem is therefore a “ladder to Heaven”, and a place through which angels enter and exit our world.

Having said all that, it is easy to understand why Jerusalem is so important to the Jewish people. It is mentioned over 600 times in the Tanakh (and, it is fitting to add, not once in the Koran). It has had a nearly continuous (with minor blips) Jewish habitation and presence for some 3000 years. When the Second Temple was destroyed, the Roman historian Tacitus estimated a Jewish population in Jerusalem of 600,000, while Josephus counted over a million.

Even in the most difficult of days, Jews hung on to their holy city. When the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) arrived in 1267 following the horrors of the Crusades, he still managed to find two Jewish families. By the Ottoman period in the 16th century, Jews once again formed the largest proportion of the population. In 1818, Robert Richardson found that Jews, while not the majority, made up the single largest group of people in the city, and estimated there were twice as many Jews as Muslims. Prussian consul Ernst Gustav Schultz noted something similar in 1844 (counting 7210 Jews to 5000 Muslims, and 3390 Christians), as did Swiss explorer Titus Tobler two years later (7515 Jews to 6100 Muslims, and 3558 Christians).

Today, there are over half a million Jews in Jerusalem. At the time of the Temple’s destruction, the Midrash records that there were a total of 481 synagogues in Jerusalem, each with a Torah school inside (Yalkut Shimoni, Ezekiel 390). A study in the year 2000 found that Jerusalem now has over 1200 synagogues. This is undoubtedly more than at any time in its history. The borders of Jerusalem today are larger than they have ever been, and the city is flourishing in every way. Indeed, this is one of the great prophecies of the End of Days, and Jerusalem will only grow further, as the Talmud (Bava Batra 75a-b) states:

In the time to come, the Holy One, blessed be He, will add to Jerusalem a thousand gardens, a thousand towers, a thousand palaces, and a thousand mansions; and each will be as big as Sepphoris in its prosperity…

Four Holy Cities

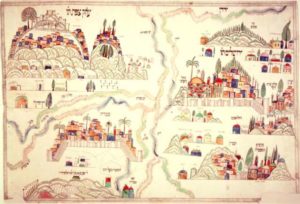

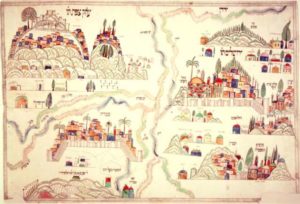

A 19th century map of the Four Holy Cities

While the entire land of Israel is holy, and Jerusalem is undoubtedly its focal point, it is often said that Judaism has four holy cities. In addition to Jerusalem, the other three are Hebron, Tzfat, and Tiberias. Where did this notion of four holy cities come from?

In 1492, the Spanish expelled all of their Sephardic Jews. It is reported that the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II said of his Spanish counterpart at the time something along the lines of: “They tell me that Ferdinand of Spain is a wise man, but he is a fool, for he takes his treasure and sends it all to me.” Bayezid sent his navy to bring many of those Jews to his empire, especially to the cities of Thessaloniki and Izmir. Others went to Europe, North Africa, or even the New World, while some headed straight for the Holy Land.

In 1516, the Ottoman Turks conquered the Holy Land, allowing even more Jews to settle there. Many Jews relocated, particularly to Hebron and Tzfat, in addition to Jerusalem. Just a few decades later, the great Donna Gracia (1510-1569) and her nephew Don Joseph Nasi (1524-1579) sought to re-establish a semi-autonomous Jewish state in the Holy Land (three centuries before the Zionist movement!) and actually received a permit from the Sultan to settle Jews in Israel. Don Joseph particularly liked the Tiberias area, and was officially given the title “Lord of Tiberias” by the Ottoman throne.

By 1640, the Jewish communities of Jerusalem, Hebron, and Tzfat were very large, though still struggling financially. Throughout history, it was customary for Jewish communities in the diaspora to send money in support of Jewish communities in the Holy Land. This was seen as both a huge mitzvah—supporting those brave Jews that risked so much to stay in their ancestral land—as well as a way for Jews in the diaspora to participate in the monumental mitzvah of dwelling in the Promised Land. The Jewish communities in Jerusalem, Hebron, and Tzfat regularly sent emissaries across the diaspora to collect funds. Around 1640, the leaders of these three communities got together and decided to unite their funds. They became known as the “Three Holy Cities” (or by their acronym יח״ץ), and sent a single emissary to collect on behalf of all three. By 1740, the Jewish population of Tiberias had grown large enough that they joined the fund, too, and thus was formed the “Four Holy Cities”. (Some say that the Four Cities first merged earlier, in the late 16th century.)

Still, while the concept of “Four Holy Cities” might be recent, it is by no means meaningless or coincidental.

Four Aspects of Judaism

Why did Jews migrating to Israel choose to settle in these four cities in particular? It was not by random chance that Jews yearned to settle in them! These cities are indeed of greatest significance to the Jewish population, which is why Jews went there in the first place. Jerusalem has already been discussed; what of the others?

Tzfat is first mentioned in the Talmud as a place where signal fires were lit so that all the surrounding towns would know the new moon had been announced (Yerushalmi, Rosh Hashanah 11b). By the end of the 16th century it had become renowned as the centre of Kabbalah, and was the home of greats like the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) and the Radbaz (Rabbi David ibn Zimra, 1479-1589), the Arizal (Rabbi Itzchak Luria, 1534-1572) and Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620). It is where Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575) produced the Shulchan Arukh, still the foremost code of Jewish law.

Hebron was King David’s first capital before he built Jerusalem. It was there that he was accepted as king by the nation, and where he was anointed by the elders of Israel (II Samuel 5:3). It is the birthplace of the Davidic dynasty. Meanwhile, Hebron is home to the Cave of the Patriarchs, the resting place of the forefathers and foremothers of Israel. It is explicitly mentioned in the Torah multiple times. Later, it would become a centre of Jewish mysticism, too, like Tzfat, and was home to the great Kabbalists Rabbi Malkiel Ashkenazi (d. 1620) and Rabbi Eliyahu de Vidas (1518-1587), among others.

Tiberias is actually built on an older Biblical town. It is quite ironic that it is referred to as Tiberias, named after the Roman emperor Tiberius (42 BCE-37 CE). To the ancient Jews it was “Rakat”, as we read in the Tanakh and Talmud (Joshua 19:35, Megillah 5b). Tiberias did not participate in the Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire, and was spared both in 70 CE and in 135 CE. This is why many Jews resettled there, and it is where the Sanhedrin was re-established around 150 CE. Rabbi Akiva was buried in Tiberias, and Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai called it home. Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi lived there, too, and it is where he put together the Mishnah. The Talmud Yerushalmi followed, and was similarly composed mainly in Tiberias.

Tiberias continued to have a large Jewish population for centuries. The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204) was buried there in 1204. The city was completely destroyed during the Mamluk period, and when Rabbi Moshe Bassola (1480-1560) visited in 1522, he found nothing but a few households and many marauding Arabs. This is where Donna Gracia and Don Joseph come into the picture, receiving a permit from the Ottomans in 1561 to rebuild the city and settle Jews there. It was Don Joseph who rebuilt its ancient walls (dating back to the time of the Biblical Joshua), and planted its first orchards.

In short, these three additional Holy Cities all played instrumental roles in Jewish history. Without their flourishing Jewish communities—which produced the Mishnah and Talmud Yerushalmi, the Shulchan Arukh and the bulk of Kabbalah—Judaism as we know it would not exist. So, while the notion of “Four Holy Cities” may have formally originated in the 18th century, its spiritual origins go back much further.

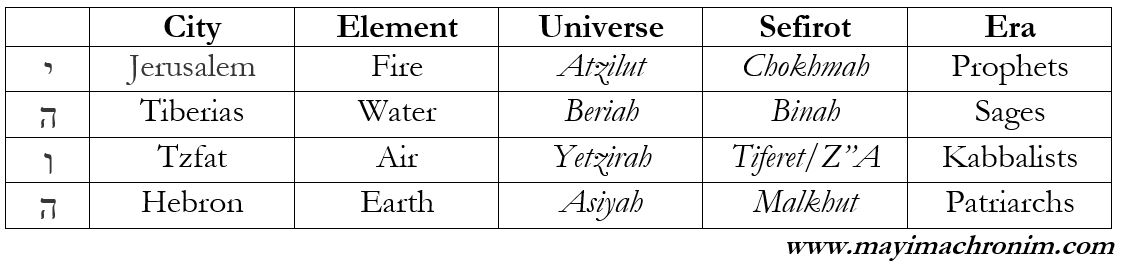

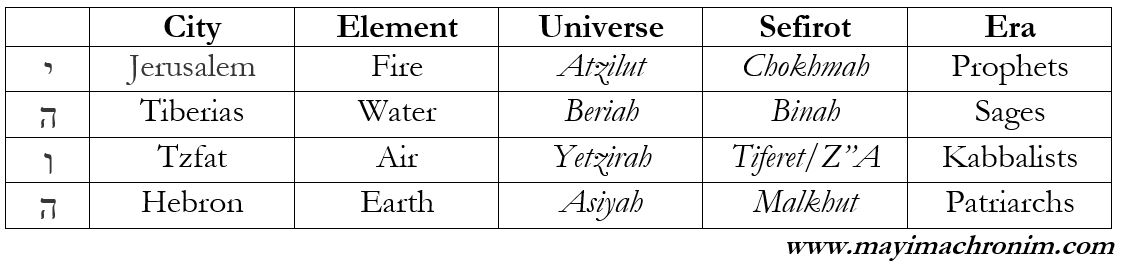

Each city can be said to parallel a different facet of Judaism. Hebron plays a big role in the Chumash, while Jerusalem is the primary locale of the rest of Scripture, the Nevi’im and Ketuvim. Tiberias is the home of the Mishnah and Talmud, while Tzfat is the capital of Kabbalah. Hebron represents the Patriarchs, Jerusalem represents the Prophets, Tiberias the ancient Sages, and Tzfat the Kabbalists. In fact, each of these four cities symbolizes something even more primordial.

The Four Elements

Ancient texts from all around the world, as well as Jewish mystical texts, speak of four primordial elements: air, water, fire, and earth. Sefer Yetzirah, one of the oldest Kabbalistic texts, explains how God formed all of Creation starting with these fundamental entities. First came the most ephemeral and intangible of them: air. This came out of God’s Spirit, which itself came out of the Ten Sefirot (1:9-10). Then came “water from breath” (1:11), and then “fire from water” (1:12). These three elements correspond to the three “mother” letters of the Hebrew alphabet: Aleph (for avir, “air”), Mem (mayim, “water”), Shin (esh, “fire”). Only much later was created the most physical and tangible of the elements, earth.

These four primordial elements neatly correspond to the four scientific elements upon which all life is built: hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon (sometimes abbreviated as “HONC”). Hydrogen is the key element in water (its name literally means “water-maker”), and it is specifically those intermolecular hydrogen bonds that give water most of its incredible properties. Oxygen is what feeds a flame, and without it no fire burns. Nitrogen makes up 78% of our air, while carbon fills our earth, whether in coal, oil, diamonds, or countless other substances.

The Four Holy Cities also correspond to those four primordial elements. Tzfat is atop a mountain, and with an elevation some 900 metres above sea level, is the highest city in Israel. It is quite literally “up in the air”. Tiberias, meanwhile, rests on the shores of Israel’s most important body of water, the Galilee. Hebron is associated with that plot of earth that Abraham purchased, and within which the patriarchs are buried. And Jerusalem is where the Eternal Flame, esh tamid, burned for centuries, and will be reignited once more in the near future.

Four Holy Cities Summary Table