Where did the concept of animal sacrifices really come from? Why are there so many sacrificial procedures described in the Torah? Will there be sacrifices in the future Third Temple in Jerusalem? And what does it all have to do with human consumption of meat? Is the vegan diet of Adam and Eve ideal for mankind? Find out in this eye-opening class! Plus: Did God really command Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac? What did meat consumption have to do with the Great Flood? And what did the fallen angels have to do with it?

Tag Archives: Jacob

Mysteries of Shemini Atzeret & Simchat Torah

Tonight we usher in Shemini Atzeret, the final “eighth” day following Sukkot, which is technically a distinct holiday of its own. In the diaspora—where we keep two days of yom tov—the second day of Shemini Atzeret is Simchat Torah, when we start a new Torah reading cycle with a big celebration. In Israel—where one yom tov is observed—Simchat Torah and Shemini Atzeret are on the same day. The Torah does not actually say what the purpose of Shemini Atzeret is, and why it is distinct from Sukkot. Simchat Torah is not mentioned in the Torah at all! What is the real meaning behind these mysterious festivals?

‘The Feast of the Rejoicing of the Law at the Synagogue in Livorno’ by Solomon Hart (1850)

The Torah itself only tells us that we should have one extra holiday after Sukkot, a yom tov in which we should not do any work and in which we should bring offerings to Hashem (Leviticus 23:36, 39). Commenting on this, Rashi famously cites our Sages and quotes God saying “‘I keep you back with Me [atzarti] one more day’—like a king who invited his children to a banquet for a certain number of days. When the time arrived for them to leave, he said, ‘Children, I beg you, please stay one more day with me; it is so hard for me to part from you!’” The Zohar adds to this a beautiful explanation:

As discussed in the recent class here, Sukkot is a holiday envisioning the future, not commemorating the past. The prophet Zechariah tells us (in chapter 14) that in the forthcoming Messianic age, all the nations of the world will come to Jerusalem to celebrate Sukkot with us. Sukkot will become an international festival! And so, the Zohar says, once all the nations of the world leave following seven days of Sukkot in Jerusalem, only the Jewish people will remain for one more day of celebration just for us—Shemini Atzeret. That’s why the Torah says atzeret tihyeh lakhem, “it shall be an atzeret for you” (Numbers 29:35), meaning specifically for the people of Israel and not the other nations of the world who will come to celebrate Sukkot! (See Zohar I, 64a)

But why is this particular date special? What happened in history on Shemini Atzeret to make it a holiday to begin with?

Secrets from Jubilees

The ancient (apocryphal) Book of Jubilees provides an incredible origin to Shemini Atzeret. Recall that Jubilees was excluded from the Tanakh by most Jewish communities (although it was included in the Ethiopian Tanakh and in the ancient Essene Tanakh, and many copies have been found among the Dead Sea Scrolls). Nonetheless, it was always studied and referenced throughout history, and many parallel passages are found in our Midrashim (for more on this, see here).

The setup for Shemini Atzeret begins in Chapter 31 of Jubilees, where we read how Jacob destroyed all the idols in his household (paralleling Genesis 35:2). Jubilees says that it was here that Rachel told her husband about the teraphim she took from Lavan, and handed them over to Jacob to be destroyed. Jacob then finally goes to visit his parents after decades away from them. Instead of taking his entire big family on the journey, he decides to bring only his sons Levi and Judah. Isaac and Rebecca give these two grandsons special blessings, and Isaac gives Levi a blessing to be priestly and Judah to be royal. This is Jubilees’ explanation for why later in history the tribe of Levi would become priests and the tribe of Judah would give rise to the line of kings. It also explains why these are the two tribes that survived throughout history, to this day, while the other tribal lineages have been lost.

In Chapter 32, Jacob fulfils his promise to tithe everything he has to Hashem—and that includes his children! So he lines them all up and counts from the youngest up, the tenth being Levi. Thus, Levi is chosen to be the “tithe”, and to dedicate his life to Hashem. Levi has a dream where God confirms that he will be the family priest. He then builds an altar and begins his work of sacrificial offerings. The family has a seven-day celebration, going out into the fields and dwelling in booths. According to Jubilees, this is the original Sukkot!

On the eighth day, after the seven-day Sukkot is over, Hashem appears to Jacob again. This is where He affirms that “You shall be called Jacob no more, but Israel shall be your name” (Genesis 35:10). The following verses in the Torah tell us that God blesses Jacob to be fruitful, and promises to Jacob the Holy Land, and tells him that nations and kings will emerge from him. This special day is Shemini Atzeret! Fittingly, Jubilees adds that God then reveals to Jacob all the things that will happen in the End of Days, engraved upon seven tablets. Again, we see the link between Sukkot-Shemini Atzeret and the End of Days, the holiday being more about envisioning the future then commemorating the past.

In this way, Jubilees shows how Jacob celebrated Sukkot and Shemini Atzeret long before Sinai, confirming our Sages statement that the Patriarchs observed the whole Torah and marked all the holidays—even though their lives pre-dated Sinai and they did not have a physical Torah in their hands.

What about Simchat Torah? There is no explicit mention of it in Tanakh, and not in Mishnah or Talmud (and not in Jubilees either). This is a much more recent holiday. Where did it come from, and why?

Celebrating the Torah

In olden times, the Torah was typically read over the course of not one year, but three years. (Earlier still, in Biblical times, it was read publicly over the course of seven years—more on that below.) It was in the Persian Empire that the Babylonian sages sped up the cycle to read the whole Torah once a year (see Megillah 29b). Even as late as the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204), he writes in the Mishneh Torah that there were still some minority communities who followed a three-year cycle, although it had become nearly universal to follow a one-year cycle (Hilkhot Tefillah 13:1). The Rambam codifies that the Torah begins anew with parashat Beresheet on the Shabbat following Sukkot. He then states that it was Ezra the Scribe who instituted the yearly cycle. There is no contradiction here, because Ezra came to Israel from Babylon.

Why start with Beresheet in the fall? Why not in Nisan, which is the first month of the Jewish calendar? This goes back to the debate between Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehoshua on when Creation took place (Rosh Hashanah 10b-11a). The former said that Creation took place in Tishrei, while the latter argued it took place in Nisan. Rabbi Eliezer brings multiple proofs for his position, including the fact that the Torah states there had not yet been precipitation and then God “raised a mist” and made it rain before creating Adam (Genesis 2:5-6). So, the creation of Adam is clearly tied to the start of the rainy season, meaning Creation must have been in Tishrei!

Another proof is that the Torah says God created every species in its mature, adult form, including trees already containing fruits on their branches. When do find that trees are full of fruit and ready for harvest? In Tishrei! (Sukkot marks the final fruit harvest of the year.) Thus, it is fitting to read Beresheet in the fall, since the Torah begins with a description of a divine spirit “hovering over the waters”, the separation of upper and lower waters and establishment of the water cycle, the first rains, and trees full of fruit. And by the Rambam’s time, the yearly Torah-reading cycle had become essentially universal. However, the Rambam does not mention Simchat Torah.

Some four hundred years later, the Shulchan Arukh (in Orach Chaim 669) does mention Simchat Torah, but very briefly. The way Rav Yosef Karo (c. 1488-1575) phrases it makes it seem like it’s only outside of Israel—where people have to keep two yom tovs—that the second yom tov is called Simchat Torah. The Ashkenazi gloss of the Rama (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, 1530-1572) adds the details that we are familiar with: to remove all the Torah scrolls from the ark and have a big celebration, with hakafot, song and dance, and aliyot for all. The Rama’s language suggests this was the practice specifically in European lands. He cites the Arba’ah Turim of Rabbi Yakov ben Asher (“Ba’al haTurim”, c. 1269-1343) who explicitly says it was “the custom in Ashkenaz” to hold a big celebration and feast in honour of the completion of the Torah reading cycle and the start of a new one. The Ba’al haTurim was born in Ashkenaz but moved with his family to Spain around the year 1300, and became a rabbi among Sephardim. It could well be that his family of Ashkenazi rabbis introduced Simchat Torah to the Sephardic world. By the time of the great Abarbanel (1437-1508)—who was advisor to the Spanish crown and was given an exemption from the Spanish Expulsion, but famously chose to leave with his people—we see that Simchat Torah was observed in Spain, too, and Abarbanel explains (in his commentary on Deuteronomy 31:9):

It is written that each and every year, the high priest or the prophet or judge or gadol hador would read on Sukkot a portion of Torah, and would conclude reading the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers over the course of six years, and then in the seventh year (the Sabbatical), the king would read on Sukkot the book of Deuteronomy, and would complete the Torah. Thus, the custom has remained until our days, that on the eighth day festival, Shemini Atzeret, on the last day we have Simchat Torah, on which we complete the Torah…

Rav Yosef Karo himself was born in Spain, and ultimately settled in Tzfat where he was the chief rabbi. His contemporary was the great Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572), who lived out his final years in Tzfat and revolutionized Judaism with his mystical teachings. The Arizal had an Ashkenazi father and a Mizrachi mother, and was raised in Egypt by his uncle, studying under great rabbis like the Radbaz (Rabbi David ben Solomon ibn Zimra, 1479-1573, also born in Spain). The Arizal played a big role in fusing together Sephardic, Mizrachi, and Ashkenazi practices. He revealed various mystical meditations on Simchat Torah, and particularly on the hakafot. And so, from Tzfat, Simchat Torah spread to the Mizrachi world as well, and it soon become universal to hold a big Simchat Torah celebration—with the additional details and practices mentioned by the Ba’al haTurim and Rama that first originated in Ashkenaz.

Celebrating the Tree of Life

We can now clearly piece together the evolution of Simchat Torah. It officially began in Central Europe. The first explicit mention of the term “Simchat Torah” appears to be in the 11th century Machzor Vitry, written by Rav Simcha of Vitry, France, a student of Rashi. Simchat Torah might trace back to an earlier custom among the Geonim to have a big celebration upon completion of the Torah-reading cycle. The Rambam, who came from a long line of Sephardic rabbis, does not mention Simchat Torah in the 12th century, but the Sephardi gadol Abarbanel does speak of it in the 15th century, meaning it was adopted among Sephardim at some point in those intervening three centuries. It may have been due to the Ba’al haTurim’s family who immigrated from Ashkenaz to Sepharad around the end of the 13th century.

At the same time, in 1290 CE, came the first publication of the Zohar, in Spain. The Zohar (III, 97a) does mention Simchat Torah, calling it by its Aramaic name Hedvata d’Oraita (which is likely what it would have originally been called among the Babylonian Geonim). The Zohar gives a beautiful explanation as to why we celebrate with the Torah specifically on Shemini Atzeret. As noted above, Shemini Atzeret is the festival that is only for Israel, once all the nations of the world leave after Sukkot, and once the seventy bulls offered on behalf of the seventy nations was complete. Now, only Israel remains, delighting with Hashem once last time before going off to start a new year. And what makes our relationship with Hashem special? What makes us unique compared to the other nations? The Torah! It is our covenant with Hashem, with Torah as contract, and our devotion to its laws and its study. So, Shemini Atzeret is the ideal time to celebrate the Torah, to dance with the Torah, renew our commitment to Torah, and start a new Torah-reading cycle.

We see how, between the Zohar and the Arba’ah Turim, Simchat Torah spread throughout Sepharad; and after the Spanish Expulsion, to North Africa and the Middle East and Mizrachi communities as well. Today it has become a beautiful, universal practice in all Jewish communities, a public display of faith and commitment to Hashem and His Torah. And this ties right back into what the Zohar says about Simchat Torah:

Intriguingly, the Zohar gives it another name, calling it Hedvata d’Ilana, a celebration of the Tree of Life. The simple meaning is that King Solomon called the Torah a “Tree of Life for those who grasp it” (Proverbs 3:18). On Simchat Torah we grasp the Torah quite literally! On a deeper level, connecting Simchat Torah to the Tree of Life is yet another allusion to Creation, and to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. At the start of the year, we have a new opportunity to “choose life” (Deuteronomy 30:19), to live a godly life of divine service, a life of blessing, righteousness, kindness, and goodness. It is the opportune time to set resolutions for the new year, so that it should be a fruitful, productive, happy, and blessed year for all.

Chag sameach!

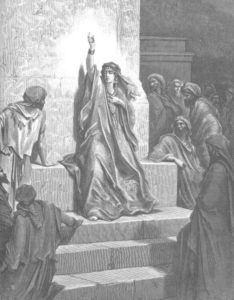

Seven Prophetesses of Israel

This week’s parasha, Tetzave, continues with the description of the construction of the Mishkan and its holy vessels. The walls of the Mishkan were held up by 48 pillars of acacia wood, plus 7 lintel beams. The Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) comments on Exodus 26:15 that the 48 pillars correspond to the 48 male prophets named in Tanakh. The 7 lintels, meanwhile, correspond to the seven generations between Abraham and Moses. This second comment is strange since we would expect the Ba’al haTurim to instead say that the 48 pillars correspond to the 48 male prophets while the 7 lintels correspond to the 7 female prophetess, as enumerated by our Sages. We are taught in the Talmud (Megillah 14a) that the Seven Prophetesses of Israel were Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther. Of course, there were other female prophetesses in ancient Israel, just as there were many more than 48 male prophets. These 55 are specifically mentioned because we actually have their prophecies recorded, or because they are explicitly referred to as “prophets” in Tanakh (as Miriam is in Exodus 15:20).

The Seven Prophetesses are particularly special because they are sometimes described as being even greater than their male counterparts. For instance, when Abraham turned to God concerned about Sarah’s plans, God told him to listen to Sarah and do as she says (Genesis 21:12). Deborah is described as being greater than Barak, and Hannah more in tune than Eli the kohen gadol. Amazingly, Rav Yitzchak Ginsburgh points out that when the Torah says there will be more great prophets in the future like Moses to lead the people (Deuteronomy 18:15), the gematria of that entire phrase (נָבִיא מִקִּרְבְּךָ מֵאַחֶיךָ כָּמֹנִי יָקִים לְךָ יהוה אֱלֹהֶיךָ אֵלָיו תִּשְׁמָעוּן) is 1839, exactly equal to the value of the names of the Seven Prophetesses! (שָׂרָה מִרְיָם דְּבוֹרָה חַנָּה אֲבִיגַיִל חֻלְדָּה אֶסְתֵּר) That might explain why the 7 lintels lie “above” the 48 pillars, as if implying that the female prophetess were greater than the male ones. What exactly was so great about them?

Sarah’s prophecies ensured that Isaac would inherit the covenant and continue the divine line started by Abraham. Miriam inspired her parents to reunite after their separation, resulting in the birth of Moses. She later guided baby Moses in the river and ensured his survival. There would be no Moses without Miriam! Deborah saved Israel from the cruel subjugation of Sisera, and composed one of history’s ten divine songs. From Hannah we learn how to pray (Berakhot 30b-31b), and Abigail taught us about the afterlife (including terms like kaf hakelah and tzror hachayim). Huldah foresaw the destruction of Judah at the time of King Yoshiyahu (and it is possible this prophecy resulted in the pre-emptive move to save the Ark of the Covenant and hide it for the distant future). Esther saved the Jewish people from near-extinction, and produced one of the 24 books of Tanakh.

We can further parallel the Seven Prophetesses to each of the seven lower Sefirot (as all things seven in Creation are connected, and emerge from the lower Seven). Miriam embodied the waters of Chessed, taking care of her little brother, nurturing him as an infant, and later providing all the Israelites with water in the Wilderness through her miraculous well. It is specifically by the waters of the Red Sea that the Torah calls her a prophetess. Sarah, on the other hand, was Gevurah, representing severity and judgement. She made the tough call to expel Hagar and Ishmael. While Abraham was the man of Chessed, Sarah was clearly his Gevurah counterpart. (In the next generation it was flipped, with Isaac embodying Gevurah and his wife Rebecca representing Chessed—introduced in the Torah as carrying a water jug on her shoulders and kindly providing abundant waters to the camels of Eliezer.) Deborah was the judge and Torah scholar, the greatest halakhic authority of her day, personifying Tiferet, the source of Torah and emet, “truth”.

Abigail taught us about eternal life—the eternity of Netzach. She introduces us to the transmigrations of the soul following death, calling it kaf hakelah, which the Zohar (II, 99b) explains means that the soul is flung from one body to another, from one reincarnation to another, like a stone flung from a sling. The Arizal (Rabbi Itzhak Luria, 1534-1572) gives the same explanation for kaf hakelah in Sha’ar haGilgulgim (Ch. 22). Incredibly, he reveals that Abigail was herself a reincarnation of Leah! (Ch. 36) Her original husband Naval was a reincarnation of Lavan, while David had a spark of Jacob. Just as Jacob worked for Lavan, David worked for Naval. And just as Lavan cheated Jacob out of his wages, Naval did the same to David. The tikkun here was that Jacob did not wish to marry Leah, and she always felt secondary and unloved. This was rectified with Abigail, as David did indeed wish to marry her and gave her the attention she deserved. Nor was there any trick in getting David to marry Abigail, which is what had happened previously with Lavan tricking Jacob into marrying Leah.

Hannah taught us lehodot, to acknowledge Hashem and to be grateful. She sang a majestic prayer-song of thanksgiving. This is, of course, the Sefirah of Hod. The result of her prayers was Samuel, who went on to anoint the first kings of Israel. Huldah foresaw the destruction of Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah due to the violation of the covenant, the brit associated with foundational Yesod. She lived in Jerusalem (II Kings 22:14), the place of the “Foundation Stone”, even hashetiyah. In fact, the southern wall of the Temple Mount has an ancient gate referred to as the “Huldah Gate”. Huldah also relayed to King Yoshiyahu that he will be spared destruction and die in peace (II Kings 22:20) because of his genuine teshuvah and rectification of his brit. The Talmud (Megillah 14b) says Huldah was a descendant of Rahav, who had an immoral past and rectified her own sphere of Yesod, meriting to marry Joshua and become the mother of many great prophets and figures, including Jeremiah and Neriah.

Finally, Esther is the embodiment of a queen, the final “feminine” Sefirah of Malkhut. In fact, the word “Malkhut” appears ten times in the Megillah, more than in any other book of Tanakh! And we read in Esther 2:17 that “The king loved Esther more than all the other women… so he set a royal crown [keter malkhut] on her head and made her queen…” Recall the teaching of our Sages that when the Megillah mentions “the king” without a name or qualifier, it can also be read as referring to The King, to Hashem. And so, it is as if God Himself crowned Esther with Malkhut.

In these ways, the seven lower Sefirot parallel the Seven Prophetesses, who attained divine inspiration on the highest levels, and ensured the survival of Israel and Judaism throughout the centuries.