This week (in the diaspora) we read the parasha of Kedoshim, literally “holy”. The name of the parasha is particularly significant, for although observing the entire Torah makes us holy, it is the laws of this parasha specifically that truly distinguish a holy person from the rest. This includes one of the most difficult mitzvot to fulfil: loving your fellow as yourself (Leviticus 19:18). It also includes honouring one’s parents (19:3 and 20:9), another one which our Sages describe as among the hardest to fulfil (Kiddushin 31b). Then there’s the mitzvah of not gossiping, which the Talmud holds to be the one transgression that everyone is guilty of to some extent (Bava Batra 165a). Several times in the parasha God reminds us to carefully observe Shabbat, which has so many halachic intricacies that it, too, is among the hardest mitzvot to fulfil properly.

Finally, towards the end of the parasha there is a long list of sexual prohibitions. Rashi comments (on Leviticus 19:2) that when God tells us to be kedoshim, “holy”, He is specifically referring to sexual purity. One can never be holy as long as they engage in any kind of sexually immoral behaviour. It should be noted that sexual purity does not mean celibacy. Unlike in some other religions and cultures, Judaism does not find sexual intimacy inherently sinful. On the contrary, when it is done between a loving couple in a kosher, monogamous union, then it is a holy act.

The classic Jewish text on sexual intimacy is Iggeret haKodesh, “the Holy Letter”. There we read how kosher sexual intimacy has the power to bring down the Shekhinah, God’s Divine Presence, “in the mystery of the Cherubs”. Interestingly, one of the Scriptural proofs for this is Jeremiah 1:5, where God says that before the prophet Jeremiah was born, and before he was even conceived, he was “sanctified” (hikdashticha) by God. An alternate way of reading this verse is that the act leading to conception is itself sanctified. The Arizal (Rabbi Isaac Luria, 1534-1572) added that at the climax of sexual intimacy, a couple “shines with the light of Ain Sof”, God’s Infinite Eminence (see Sha’ar HaPesukim on Kohelet).

Needless to say, to attain such a level requires that the couple is totally unified spiritually, emotionally, mentally, and physically. It requires true love, going in both directions. This can be illustrated mathematically, where the gematria of love, “ahava” (אהבה), is 13, and when it flows both ways, 13 and 13 makes 26, the value of God’s Ineffable Name.

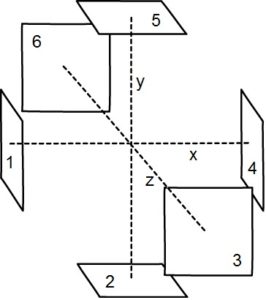

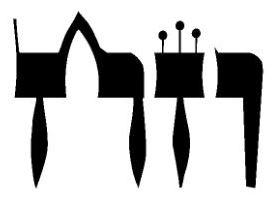

Deeper still, the male and female are represented by the letters Vav and Zayin in the holy Hebrew alphabet. The letter vav has a phallic shape, and literally means a “hook” or “connection”, while zayin is a vav with a crown on top, since the woman is described as the “crown” of her husband (עטרת בעלה, as in Proverbs 12:4). Vav has a numerical value of six, and zayin follows with seven. Six is a number that represents the physical dimension, since all things in this three-dimensional world have six sides. The seventh is what’s inside that three-dimensional space, and therefore represents the inner, spiritual dimension. Naturally, this corresponds to the physical six days of the week and the spiritual Sabbath. And it relates to the male, represented by the physical six, and the female of the spiritual seventh.

The shapes of the letters vav, zayin, and chet (right to left), according to the ktav of the Arizal.

The eighth is what transcends the three-dimensional space entirely. Eight represents infinity, and it is no coincidence that the international symbol for infinity is a sideways eight. In the Hebrew alphabet, the eight is the letter Chet. This letter represents the Chuppah, “marriage canopy”, of the vav (male) and zayin (female). If you look closely, the shape of the letter chet is actually a chuppah, and underneath it stand a vav and zayin, male and female.* Under the chuppah, their eternal, infinite (eighth) bond is forged. The vav and zayin combine into one, and when six and seven combine, they once more make 13, ahava, love.

(As a brief aside, the letter that follows in the alphabet is Tet, in the shape of a “pregnant” zayin, and with a numerical value of nine to represent the nine months of pregnancy.)

The Healing Power of Iyar

The parasha of Kedoshim teaches us that the greatest mark of holiness is sexual purity, especially a pure relationship between husband and wife. It isn’t a coincidence that this parasha is always read at the start of the month of Iyar, or in the Shabbat immediately preceding it (when we bless the month of Iyar). Our Sages teach us that Iyar (איר or אייר) is a month of healing, and stands for Ani Adonai Rofecha, “I am God, your Healer” (Exodus 15:26). There is even an old Kabbalistic custom to drink the first rain of the month of Iyar, for it is said to have healing properties.

For the Israelites that came out of Egypt, Iyar was a month of healing from their horrible past in servitude. It was in this month in particular that they were preparing for their meeting with God at Mt. Sinai. More accurately, it was not a meeting but a wedding, for the Divine Revelation at Sinai is always described as a marriage, with the mountain itself serving as the chuppah. This is the essence of the Sefirat haOmer period in which we are in, when we count the days in anticipation of our spiritual “wedding”, and spend each day focused on rectifying and healing a particular inner trait.

Just as this month is an opportune time to mend one’s relationship with God, it is an equally opportune time to mend one’s relationships with his or her significant other. Fittingly, the Rema (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, 1530-1572) wrote in his glosses to the Shulkhan Aruch that a divorce shouldn’t be done in the month of Iyar! (Even HaEzer 126:7) The reason for this is based on an intriguing legal technicality:

A bill of divorce (get), just like a marriage contract (ketubah) must be incredibly precise in its language. A tiny spelling error might invalidate the entire document. Rav Ovadia Yosef (1920-2013) was especially well-known for going through countless such contracts and repairing them, especially when it comes to the spelling of names. He was an expert in transliterating non-Hebrew names into their proper Hebrew spelling to ensure the validity of the marriage (or divorce) contract.

The same is true for spelling the other parts of the document, including the date. The problem with Iyar is that it has two spellings: איר and אייר. No one is quite sure which is more accurate. Though some say it doesn’t really make a difference how you spell Iyar, the Rema maintained that it is simply better to avoid getting divorced in Iyar altogether. When we remember that Iyar is the time for sanctifying ourselves, the time to focus on becoming kedoshim, and what that really means, we can understand the Rema on a far deeper level.

Embrace Your Other Half

The fact that the root of the problem is just one extra yud in the word “Iyar” is quite appropriate. The previously-mentioned Iggeret HaKodesh presents a classic Jewish teaching about man, “ish” (איש), and woman, “ishah” (אשה): The difference between these words is a yud and hei, letters that represent God’s Name. The similarity between them is aleph and shin, letters that spell esh, “fire”. The Iggeret HaKodesh states that when one removes the Godliness and spirituality out of a couple, all that’s left is dangerous fire. For a marriage to succeed, it is vital to keep it infused with spirituality. A purely physical, materialistic relationship built on lust, or chemistry, or socio-economic convenience is unlikely to flourish.

We further learn from the above that a couple must embrace each other’s differences (the yud and the hei). One of the most frustrating things in relationships is that men and women tend to view and experience things differently. In general, any two people will view and experience the same thing differently, and it is all the more difficult when the two are building a life together. It is important to remember that it is good to be different, to have alternate viewpoints, perspectives, and opinions. We should not be frustrated by this, but embrace it and use it to our advantage.

On that note, the Torah tells us that God made Eve to be an ezer k’negdo for Adam, an “opposing helper”. More accurately, our Sages teach us that Adam was originally a singular human with both male and female parts (Beresheet Rabbah 8:1). Only afterwards did God split this human into separate male and female bodies. (This is one reason why the Torah seemingly describes the creation of man twice, in Chapter 1 and 2 of Genesis.) So, when the Torah speaks of an ezer k’negdo following the “split” of Adam, it really refers to both husband and wife. Each is a helper opposite their spouse. The term k’negdo is of great importance, for it implies that men and women are inherently different, opposites, and it is because we are opposites that we can truly help each other. There wouldn’t be much use to being exactly the same.

Fulfilling the Mitzvah of “Love Your Fellow”

From the Torah’s description of the creation of the first couple, we can extract a few essential tips for a healthy marriage. One verse in particular stands out: “Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife, and they shall be one flesh.” (Genesis 2:24) First, it is critical to keep the parents and in-laws out of the relationship. Second, husband and wife must “cleave” unto each other—spend plenty of time together, and as is commonly said, to never stop “dating”. Third, they shall be “one flesh”; one body and soul. It is vital to understand that husband and wife are a singular unit. In fact, the Talmud states that an unmarried person is not considered a “person” at all, since they are still missing their other half (Yevamot 63a). Each half should keep in mind that their spouse’s needs are their own needs. And each spouse should always have in mind not what they can get out of the other, but what they can give.

Of course, being one means loving each other as one. The Talmud famously states that a man should love his wife as much as himself, and honour her more than himself (Yevamot 62b). We can certainly apply this in reverse as well, for a wife should similarly love her husband as much as herself, and honour him more. That brings us back to the most prominent verse in this week’s parasha: “love your fellow as yourself”. In Hebrew, it says v’ahavta l’re’akha kamokha, where “fellow” is not quite the best translation. In the preceding verse, the Torah says “your brother” (achikha) and “your friend” (amitekha). What is re’akha (רֵעֲךָ)?

In the Song of Songs, King Solomon’s intimate Biblical poem, he constantly uses the term ra’ayati (רַעְיָתִי) to refer to his beloved. This is the same term used in the sixth blessing of the Sheva Berachot recited under the chuppah and during a newlyweds’ first week of marriage: sameach tesamach re’im (רֵעִים) ha’ahuvim. The newlyweds are referred to as “fellows” in love. So, while it might be a tall order to love everyone like ourselves, we can certainly at least love our spouses this way. And that might be all it takes to fulfill the mitzvah.

Our Sages teach that the month of Iyar which we have just begun is a time for healing, and we have suggested here that is a particularly auspicious time for healing marriages. As it turns out, those two may be one and the same. In one of the longest scientific studies ever conducted, researchers at Harvard University tracked the lives and wellbeing of families for nearly a century. The conclusion: the single greatest factor in ensuring healthy and happy lives (or not) was marriage. Statistically speaking, those couples that had the best relationships tended to live the happiest and healthiest lives.

Our Sages left one last hint for us to make the connection between the month of Iyar and the Sefirat haOmer period with the necessity of building healthy marriages: It is on that very same page of Talmud cited above (Yevamot 62b) that the Sages tell us about the deaths of Rabbi Akiva’s students in the Omer period—in the month of Iyar. In fact, the very next passage after the Omer one deals with marriages, and begins: “A man who has no wife has no joy, no blessing, and no goodness…”

*This is the way a chet is written according to Kabbalah, as explained by the Arizal. However, in most cases (especially in Ashkenazi tradition) a chet is written as two zayins.