This week’s Torah portion, Tzav, has a total of 96 verses. It just so happens that the numerical value of the world “Tzav” (צו) is also 96. This is a good example of a classic gematria, the Jewish numerology technique which the Mishnah describes as a “condiment to wisdom” (Avot 3:18). Over the centuries, gematria has become more and more common, and is now an inseparable part of Judaism. Rabbi Aaron Kornfeld (1795-1881) even elucidated 300 laws using the gematrias of their corresponding Torah verses (see his Tziunim l’Divrei HaKabbalah). Indeed, the ancient Baraita of Rabbi Eliezer lists gematria as one of the 32 valid principles of Torah interpretation. The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343), who uses gematria extensively in his commentary on the Torah, points out on the verse כִּי לֹא-דָבָר רֵק הוּא מִכֶּם, “it is not an empty thing for you” (Deuteronomy 32:47), that it equals the value of גימטריות, “gematrias”. In other words, gematria is not an empty or meaningless practice! Gematriot are the original “Torah codes” dating back to millennia-old teachings.

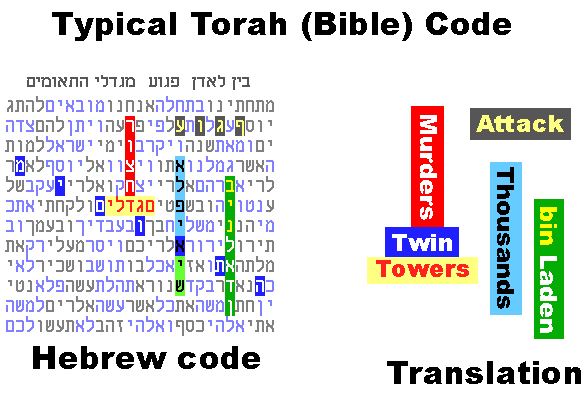

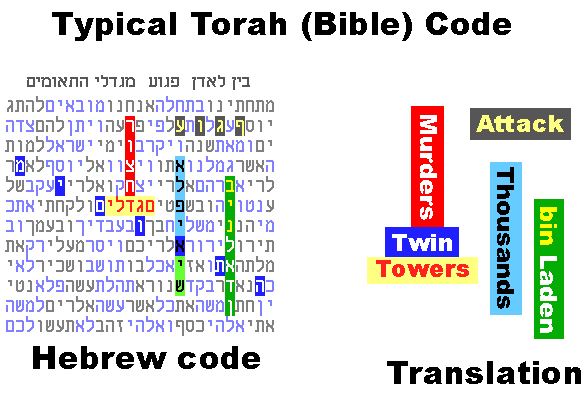

Meanwhile, in recent decades a new phenomenon has emerged and usurped the title of “Torah codes”. Today, when people think of “Torah codes” they are referring to the so-called “equidistant letter sequences” (ELS) method, often called in Hebrew (perhaps erroneously, as we shall see below) dilug, “skipping”. This method involves searching the Torah text for words that appear spaced out across large intervals. Here is one “Torah code”, courtesy of www.torahcodes.net:

Codes found in Moby Dick. Click here for more Moby Dick “codes”.

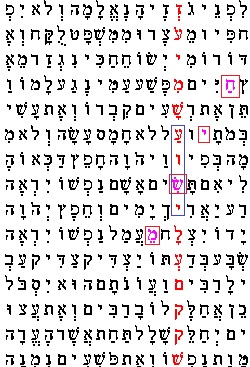

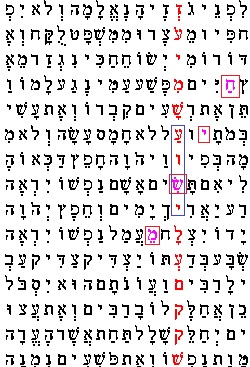

Apparently, the Torah encoded within it the terrible events of September 11, 2001. Such “codes” have been found for just about everything. Indeed, those who use the method claim that this just proves that the Torah really does literally encode all of human history within it, as per tradition. The reality, though, is that you can find everything in Torah codes because the method is inherently flawed, and when you have a text with so many letters, you will naturally be able to find just about anything you look for. Similar “prophecies” have been found in Moby Dick, and in English translations of the Bible. Worse yet, the code has been used to “prove” that Jesus is the messiah:

Professor A.M. Hasofer has pointed out that the word “Yeshua” appears hundreds of times when using ELS, and twice appears overlapped with “navi sheker”, or “false prophet”! (See Hasofer’s article in B’Or Ha’Torah #11, “Torah Code Abuse”, for a thorough analysis and debunking of Torah codes.)

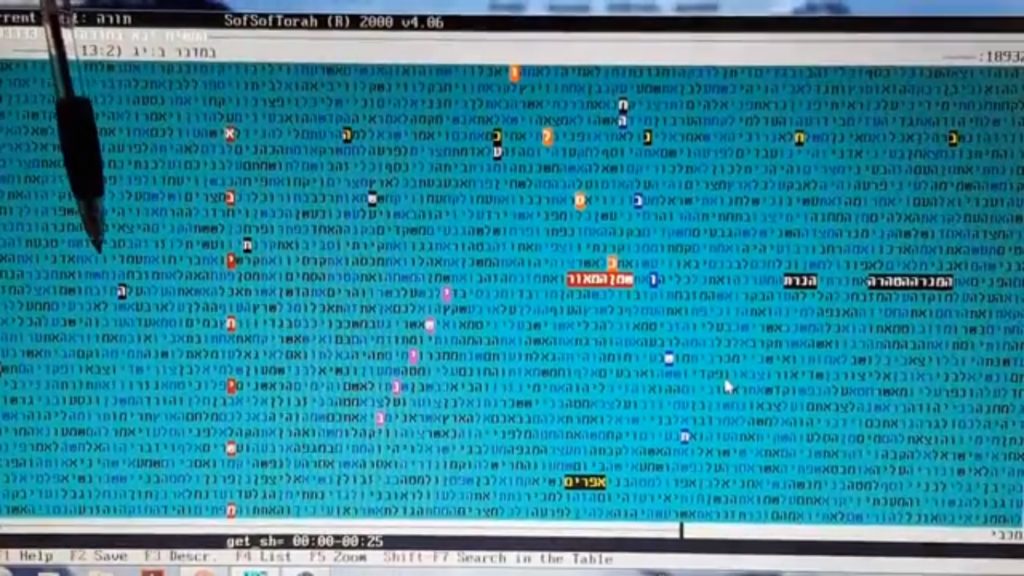

This alone should be enough to debunk Torah codes for good. (See here for why Jesus is not the messiah.) Yet, such codes are still widely spread and taught by well-meaning people. Just weeks ago on Purim I received one that claims skipping 12,196 letters from the mem in the term מור דרור (which our Sages say hints to Mordechai) will spell out מרדכי, “Mordechai”; and skipping the same 12,196 letters from the aleph in the term אסתיר פני (which our Sages say hints to Esther), will spell out אסתר, “Esther”. The kicker at the end is that supposedly Megillat Esther has exactly 12,196 letters. Immediately I went on the computer to check if this is true. Opening up a “Torah code” program, I found that if one skips 12,196 letters from either of the above, they will not get the claimed words. As I did more research, I found that the Megillah may not even have 12,196 letters. I found a similar claim that says the Megillah actually has 12,110 letters, and that the codes are from different words entirely. This one, too, did not work out in the search program! Finally, an article on Chabad.org explained the origin of the claim, dating it back to Rabbi Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandl, “the Father of Torah Codes”, who is equally famous for his heroic efforts to save Jews in the Holocaust. According to the anecdote here, Rabbi Weissmandel taught that one gets “Esther” if they count from the Torah’s first aleph, and “Mordechai” from מור דרור. Funny enough, in a footnote at the very end, Chabad.org admits that they were

not able to duplicate the above results from the same starting places, but they did find “Esther” and “Mordechai” at the cited interval in different locations. Also, some “codes” programs yield a different number of letters for Megilat Esther, such as 13,408 and 12,110. “Esther” and “Mordechai” can be found at these intervals too.

In other words, the code is completely bogus. (Why Chabad.org—otherwise a terrific resource—would publish a story and admit at the end that it is based on something false eludes me.)

True Torah Codes

In his Pardes Rimonim, the great Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) does mention a practice called dilug, along with similar practices like gematria, roshei and sofei tevot, and letter permutations. Of course, he is not at all speaking about the ELS method, which is essentially impossible without a computer, and would have been unknown to the Ramak. The dilug he speaks of is where a word emerges from letter skipping within a verse or short passage—not hundreds of letters apart, or across different chapters, parashas, or even books, as is common in ELS.

For example, there is the old story of the apostate Avner, a former student of the Ramban (which we’ve discussed before). The story ends with the Ramban showing that Avner’s name is embedded within a verse in parashat Ha’azinu; a verse that speaks specifically of God destroying the memory of those who oppose Him, like Avner.* Such small codes—with short skips in verses that actually relate to the topic at hand—may certainly be valid. Still, the Ramban himself points out (in the first gate of Sefer haGeulah) that these kinds of practices must be based on a proper tradition going back to Sinai; a person should not conjure their own gematrias and codes, for in such a way a person will be able to “prove” just about anything.

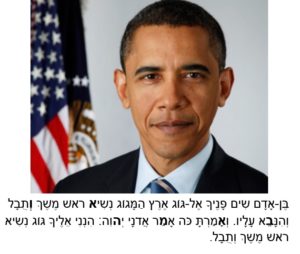

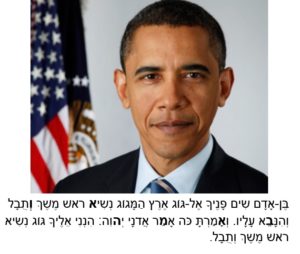

When Barack Obama was elected, many pointed out that his name appears when skipping to every seventh letter from the aleph in the word “nasi” or “president” in the famous apocalyptic passage of Gog u’Magog (Ezekiel 38:2-3). Apparently, Obama did not fulfil his “prophesied” role of bringing the apocalypse.

“Bible Codes” abound on YouTube. This video has a code suggesting Mashiach would come during Chanukah of 5778 (ie. December 2017). The same YouTube channel still has videos going back to at least 5774 with codes proving each year to be an auspicious time for Mashiach to come!

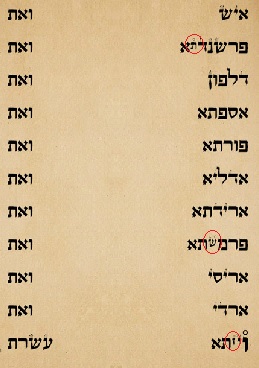

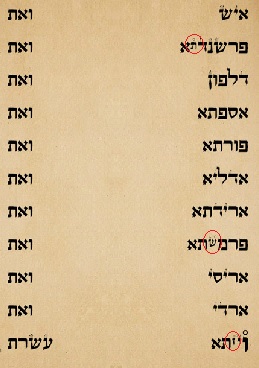

Having debunked one supposed “Purim code”, let’s conclude with a better-known Purim code. This one actually does work quite well and would be valid in the time of the Ramak, too (since it appears within one small passage, requires no computers, and is in context). It was Rabbi Weissmandl who once again first pointed it out. At the end of Megillat Esther, we read how Haman’s ten sons were hanged. The scroll shifts to a unique appearance here in listing the names of the ten sons. Traditionally, three letters in this list are written smaller than normal. Such smaller or larger letters always carry great significance wherever they appear in Scripture. The three here make up תש״ז, as if alluding to the year 5707, corresponding to the year 1946-47.

Amazingly, it was right at that time that the Nuremberg Trials concluded with the hanging of ten of the Nazi elite. In the Scroll itself we read how Esther was asked what to do with the hanged sons of Haman, and she responded: “If it please the king, let it be granted to the Jews that are in Shushan to do tomorrow also according to this day’s decree, and let Haman’s ten sons be hanged upon the gallows.” (9:13) Esther perplexingly asks for the ten sons to be hanged again!

Centuries later, ten of Hitler’s “sons”—some of his closest confidantes and co-conspirators—were hanged on the gallows, forbidden to go by firing squad as would be normal for military men.** And it’s almost as if they were aware of it all: it was reported that among the last words of the despicable Julius Streicher were: “Purimfest 1946”.

The cover of the October 28, 1946 edition of Newsweek. In its coverage of the Nuremberg executions, it states: “Only Julius Streicher went without dignity. He had to be pushed across the floor, wild-eyed and screaming: ‘Heil Hitler!’ Mounting the steps he cried out: ‘And now I go to God.’ He stared at the witnesses facing the gallows and shouted” ‘Purimfest, 1946.’ (Purim is a Jewish feast) … A groan came from inside the scaffold. Critics suggested afterward that Streicher was clumsily hanged and that the rope may have strangled him instead of breaking his neck.”

*The Avner code is actually not an ELS at all. Rather, the Ramban said that the third letter of each word spells “Avner”. These letters are not equidistant.

**The Talmud (Megillah 16a) states that Haman also had a daughter who committed suicide. In 1946, Hermann Göring was sentenced to death as well, but committed suicide the night before. Interestingly, Göring was known to be a cross-dresser. The hangings took place on October 16, 1946, just days after Rosh Hashanah 5707 (תש״ז) and fittingly, on the holiday of Hoshana Rabbah, the “Great Salvation”.