An artist’s rendition of the Ark of the Covenant

In this week’s parasha, Vayelech, we read how Moses completes writing the Torah and places it inside the Ark of the Covenant. The parasha cautions multiple times that we must not stray from this Torah, for our own benefit. At this introspective time of year, it is especially pertinent to ask: what is the benefit of living a Torah life? Why bother being religious? Aside from the simple answers, like fulfilling God’s will, earning an afterlife, or knowing this is the right way, what are the tangible, clear, positive impacts of living religiously? While there are, of course, many reasons, the following are three vital benefits of a life according to God’s Torah.

1. Personal Development that Works

Although Mussar as a large-scale movement only began in the 19th century, it has always been a central part of Judaism. The root of the word mussar (מוּסַר) literally means “restraint” or “discipline”. It is about developing self-control, awareness, morality, and being in tune with one’s inner qualities. The origin of this word is actually in the Book of Proverbs, which begin with this very term: “The proverbs of Solomon, the son of David, king of Israel, to know wisdom and mussar, to comprehend sayings of understanding, to receive mussar of reason, justice, law, and ethics.”

Before Proverbs, the word mussar appears once in the Torah, in reference to God disciplining us (Deuteronomy 11:2). The Torah instructs us to be kind and generous, humble and wise, restrained and strong; to take care of the widow and orphan, of the poor and oppressed. The prophets of Israel continued to instruct the people in this way, reminding them to be upright and just individuals. The tradition continued into the Rabbinic period, with ancient treatises like Pirkei Avot (a tractate of the Mishnah) wholly devoted to inspiring personal growth and self-improvement.

One who lives a Torah lifestyle is immersed in such teachings. Whether it’s simply reading the weekly parasha, or listening to the rabbi’s dvar; going through Avot in the weeks between Passover and Shavuot, reciting Selichot in the Forty (or Ten) Days of Repentance, or participating in the various fasts throughout the year, a religious Jew is simply unable to abstain from personal growth of some kind. We are constantly reminded of the humility of Moses, the selflessness of Abraham, the devotion of David, and the wisdom of Solomon; the incomparable patience of Hillel, the studiousness of Rabbi Akiva, and the tremendous qualities of countless other great figures. These are our heroes, and we are constantly prompted to emulate them.

There is no doubt whatsoever that a Jew who is truly religious (and not just religious in appearance, or because this is how he grew up) is continually becoming ever kinder, more humble, and generally a better human being. Now, it may be argued that even a non-religious person can focus on personal growth, and there isn’t a lack of secular self-help literature out there. This is true, but there is one key difference:

The secular person is improving for their own benefit (and the benefit of those immediately around them), while the religious person is improving not only for that benefit, but also because he understands that God demands this of him. This is important because the secular person might feel like reading a self-improvement book this week, or working hard on himself this year, but might completely forget about it next week, or might have a very busy year in which he didn’t have any time for this kind of thing at all. The religious Jew does not have this luxury. He will be fervently repenting and reflecting during the High Holiday season, and during Sefirat HaOmer and during the Three Weeks, because he is obligated to do so and cannot abstain. Religion forces us to improve. It demands that we become better, and God will judge us if we do not. This makes all the difference.

Take, for example, a person going on a diet. We all know that the vast majority of diets fail. Why is this so? Because there is nothing external forcing a person to stick to the diet. Eventually, they will slip up once, and then again, and soon enough the diet will be a forgotten thing of the past. Meanwhile, a religious person who takes upon themselves a kosher diet is unlikely to lapse. Most religious Jews happily stick to a kosher diet their entire life, despite the fact that it is so difficult. Why is such a diet successful? Because there is an external factor—God—that keeps us firmly on the diet.

Thus, while every 21st century Westerner might be engaged in some sort of secular personal development, these fleeting periods of growth are inconsistent at best, and completely ineffective at worst. Religious-based personal development works, and this is one major benefit to a Torah lifestyle.

2. The Importance of Community

While other religions may be practiced in solitude, Judaism is an entirely communal faith. The ideal prayer is in a minyan of ten or more, the ideal Torah study in pairs; marriage and child-bearing are a must, a holiday is no holiday without a large gathering, and even a simple daily meal should ideally have at least three people. Judaism is all about bringing people together. Indeed, Jews are famous for sticking together and helping each other out. There are interest-free loans, and a gmach that freely provides to those in need of everything from diapers to furniture. Jews pray together, feast together, study together, and take care of each other. A Jew can visit the remotest Chabad House in the farthest corner of the world and still feel like he is having a Shabbat meal at home.

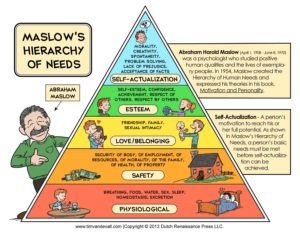

“Belongingness” fills the third rung of Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Judaism neatly facilitates the fulfilment of all five rungs.

Jews are not a nation, culture, ethnicity, or even a religion; we are, as Rabbi Moshe Zeldman put it, a family. And it is worth being a part of this extended family. We know from the field of psychology how important “belongingness” is. We know the troubles that people go through just to feel like they belong, or to have a community around them. We know how loneliness plays a key role in depression and mental illness. We know that “no man is an island”, and how important it is to be surrounded by a supportive community. The religious Jewish community is tight-knit like no other. Doors are always open for Sabbaths and holidays, charities are always open to help, and the synagogue serves as the nucleus of the community.

It is important to mention here how necessary it is for a community to stay physically close together. This is one major positive side-effect of not driving on Shabbat. In so doing, we must remain within walking distance of the synagogue, and therefore within walking distance of the whole community. The fatal error that the Conservative movement made was in allowing driving to the synagogue. As soon as this change was made, people saw no need to live close to the synagogue, and bought homes further and further away, tearing the community apart. Once the largest Jewish denomination in America, Conservative Judaism has been on a steadily decline ever since.

And so, the second major reason to be religious is the close community that comes with it. Dan Buettner, who famously spent decades studying communities around the world where people live longest and healthiest, concluded that being part of a “faith-based community” adds as much as fourteen years to a person’s life!

3. Cultivating the Mind, Mastering the Universe

Today, we find ourselves in an incredible age where centuries worth of philosophy, mysticism, and science are converging. Going back at least as far as George Berkeley (1685-1753), and really much farther to Plato (c. 427-347 BCE), philosophers have long noted the illusory nature of this physical world, and some denied the very existence of concrete material as we perceive it. The only real substance to this universe, according to them, is the mind. We live in a mental universe.

While this may sound far-fetched, the physics of the past century has brought us a great deal of proof to support it. The Big Bang taught us that the entire universe emerged from a miniscule, singular point, and that all was once in a ball of uniform energy, and that all matter (which appears to come in so many shapes and forms) really emerges from one unified source. The famous double-slit experiment showed us that all particles of matter are also simultaneously waves. Sometimes particles behave like solid objects, and other times like transient waves. The only difference is the presence of an observer, a conscious mind. Our minds literally impact our surroundings. Max Planck, regarded as the father of quantum physics, remarked:

As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clear headed science, to the study of matter, I can tell you as a result of my research about atoms this much: There is no matter as such. All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent mind. This mind is the matrix of all matter.

The “matrix” of this vast universe is the mind. Of course, this has been a central part of Kabbalah and other schools of mysticism for millennia. The Tikkunei Zohar (18b) transforms the first word of the Torah, Beresheet (בראשית), into Rosh Bayit (ראש בית), ie. that this entire universe (bayit), is a product of God’s “Mind”, or perhaps existing in His head (rosh). In fact, the Kabbalists say that if God were to stop thinking about a person even for the briefest of moments, that person would cease to exist. This is related to what we say daily in our prayers, that God “each day, constantly, renews Creation.” God is that Mind that holds the universe in existence.

And we are all a part of that Mind. After all, He made us in His image, with a small piece of that universal consciousness. This is related to the “quantum brain” hypothesis we have spoken of in the past, a scientific theory suggesting that our brains are entangled with the universe, which may itself be “conscious” in some way. In short, thousands of years of human reason, mysticism, and experimentation points to one conclusion: the only real currency in this universe is the mind.

In that case, the only thing really worth developing is the mind. The more powerful one’s mind is, the greater control one wields over the universe. This isn’t just a pretty saying, we know scientifically that our minds affect the universe around us. More personally, studies have shown that meditation (and prayer) can actually impact the way our genes are expressed! We may be able to consciously affect the biology of our bodies down to the molecular level.

The placebo effect is the best proof for this. Science still cannot explain how it is that a person who simply believes they are receiving treatment will actually heal. Surgeons have even done placebo surgeries, with results showing that people who were only led to believe they were operated on still improved just as well as those who actually went under the knife. How is this possible?

The answer is obvious: our minds have a very real, concrete, physical affect on reality. Unfortunately, most people are unaware of this latent power, and must be duped into it (as with placebos). But that power is definitely there, and its potential is immeasurable. One must only work to develop these mental powers.

Judaism provides us with exactly this opportunity. Like no other religion, Judaism is entirely based on ceaseless mental growth. We must always be studying, praying, blessing, meditating, contemplating, and reasoning. Scripture tells us to meditate upon the Torah day and night (Joshua 1:8), and the Talmud reminds us that talmud Torah k’neged kulam, learning Torah is more important than all other things. The mystical tradition, meanwhile, is built upon mental exercises like hitbonenut (“self-reflection”) and hitbodedut (“self-seclusion”), yichudim (“unifications”) and kavannot (“intentions”). A religious Jew is constantly developing not only their outer intellect, but their inner mental capacities.

And this is the true meaning of Emunah, loosely translated as “faith”. The first time the word appears in the Torah is during the battle with Amalek, following the Exodus, where we read how Moses affected the outcome of the battle by holding up his arms emunah (Exodus 17:12). Moses was very much affecting the universe around him. The only other time the word appears in the Torah itself is in next week’s parasha, Ha’azinu, where God is described as El Emunah (Deuteronomy 32:4). In light of what was said above, this epithet makes sense: God is that Universal Mind that brings this illusory physical world into existence. God is the ultimate mental power, and our minds are only tapping into that infinite pool.

Not surprisingly, the prophets and sages describe Emunah as the most powerful force in the universe. King David said he chose the path of Emunah (Psalms 119:30), while King Solomon said that one who breathes Emunah is the greatest tzaddik, and has the power to repair the world with his tongue (Proverbs 12:17-18). Amazingly, the Sages (Makkot 23b) reduced the entire Torah—all 613 mitzvot—to one verse: “The righteous shall live in his Emunah” (Habakkuk 2:4). Perhaps what they meant is that the purpose of all the mitzvot is ultimately to develop our Emunah; to strengthen our minds, to recognize the Divine within every iota of the universe, and to align our consciousness with God’s. This is the secret of the rabbinic maxim: “Make your will like His will, so that He should make His will like your will. Nullify your will before His will, so that He should nullify the will of others before your will.” (Avot 2:4)

Being religious Jews provides us with a regular opportunity (and requirement) to develop our mental faculties. Aside from the many positive health effects of doing so (including staving off mental and neurological illnesses, and even living longer), we are also given a chance to become real masters of the universe around us; to transcend our limited physical bodies. At the end of the day, that’s what life is all about.

The above is adapted from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!

The holiday of Passover commemorates the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt over three thousand years ago. The Torah tells us that because of their hasty departure, the dough of the Israelites did not have time to rise, hence the consumption of matzah. Yet, the term matzah appears in the Torah long before the Exodus! We read in Genesis 19:3 that Lot welcomed the angels into his home and “made them a feast, and baked matzot, and they ate.” Since the angels came to Lot immediately after visiting Abraham and Sarah to announce the birth of Isaac at that time next year (Genesis 18:10), the Sages learn from this that Isaac was born on Passover. Of course, the Exodus only took place

The holiday of Passover commemorates the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt over three thousand years ago. The Torah tells us that because of their hasty departure, the dough of the Israelites did not have time to rise, hence the consumption of matzah. Yet, the term matzah appears in the Torah long before the Exodus! We read in Genesis 19:3 that Lot welcomed the angels into his home and “made them a feast, and baked matzot, and they ate.” Since the angels came to Lot immediately after visiting Abraham and Sarah to announce the birth of Isaac at that time next year (Genesis 18:10), the Sages learn from this that Isaac was born on Passover. Of course, the Exodus only took place