In this week’s parasha, Pinchas, we read about the righteous daughters of Tzelofchad. Recall that the five daughters (Machlah, Noa, Haglah, Milkah, and Tirzah) had no male siblings, and their father had passed away, so they inquired about their inheritance. Are daughters allowed to inherit? It might sound like a straight-forward “yes”, but it was much more complicated in ancient Israel. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Esther

Are “Torah Codes” Legit?

This week’s Torah portion, Tzav, has a total of 96 verses. It just so happens that the numerical value of the world “Tzav” (צו) is also 96. This is a good example of a classic gematria, the Jewish numerology technique which the Mishnah describes as a “condiment to wisdom” (Avot 3:18). Over the centuries, gematria has become more and more common, and is now an inseparable part of Judaism. Rabbi Aaron Kornfeld (1795-1881) even elucidated 300 laws using the gematrias of their corresponding Torah verses (see his Tziunim l’Divrei HaKabbalah). Indeed, the ancient Baraita of Rabbi Eliezer lists gematria as one of the 32 valid principles of Torah interpretation. The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343), who uses gematria extensively in his commentary on the Torah, points out on the verse כִּי לֹא-דָבָר רֵק הוּא מִכֶּם, “it is not an empty thing for you” (Deuteronomy 32:47), that it equals the value of גימטריות, “gematrias”. In other words, gematria is not an empty or meaningless practice! Gematriot are the original “Torah codes” dating back to millennia-old teachings.

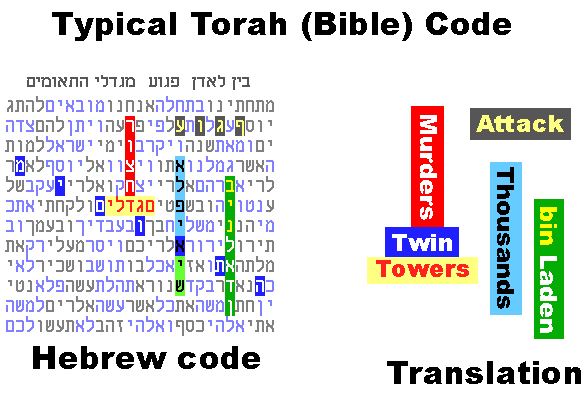

Meanwhile, in recent decades a new phenomenon has emerged and usurped the title of “Torah codes”. Today, when people think of “Torah codes” they are referring to the so-called “equidistant letter sequences” (ELS) method, often called in Hebrew (perhaps erroneously, as we shall see below) dilug, “skipping”. This method involves searching the Torah text for words that appear spaced out across large intervals. Here is one “Torah code”, courtesy of www.torahcodes.net:

Codes found in Moby Dick. Click here for more Moby Dick “codes”.

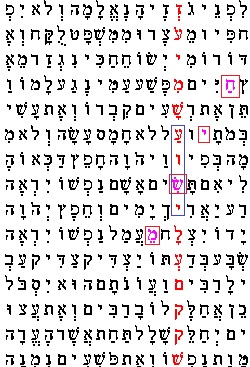

Apparently, the Torah encoded within it the terrible events of September 11, 2001. Such “codes” have been found for just about everything. Indeed, those who use the method claim that this just proves that the Torah really does literally encode all of human history within it, as per tradition. The reality, though, is that you can find everything in Torah codes because the method is inherently flawed, and when you have a text with so many letters, you will naturally be able to find just about anything you look for. Similar “prophecies” have been found in Moby Dick, and in English translations of the Bible. Worse yet, the code has been used to “prove” that Jesus is the messiah:

Professor A.M. Hasofer has pointed out that the word “Yeshua” appears hundreds of times when using ELS, and twice appears overlapped with “navi sheker”, or “false prophet”! (See Hasofer’s article in B’Or Ha’Torah #11, “Torah Code Abuse”, for a thorough analysis and debunking of Torah codes.)

This alone should be enough to debunk Torah codes for good. (See here for why Jesus is not the messiah.) Yet, such codes are still widely spread and taught by well-meaning people. Just weeks ago on Purim I received one that claims skipping 12,196 letters from the mem in the term מור דרור (which our Sages say hints to Mordechai) will spell out מרדכי, “Mordechai”; and skipping the same 12,196 letters from the aleph in the term אסתיר פני (which our Sages say hints to Esther), will spell out אסתר, “Esther”. The kicker at the end is that supposedly Megillat Esther has exactly 12,196 letters. Immediately I went on the computer to check if this is true. Opening up a “Torah code” program, I found that if one skips 12,196 letters from either of the above, they will not get the claimed words. As I did more research, I found that the Megillah may not even have 12,196 letters. I found a similar claim that says the Megillah actually has 12,110 letters, and that the codes are from different words entirely. This one, too, did not work out in the search program! Finally, an article on Chabad.org explained the origin of the claim, dating it back to Rabbi Chaim Michoel Dov Weissmandl, “the Father of Torah Codes”, who is equally famous for his heroic efforts to save Jews in the Holocaust. According to the anecdote here, Rabbi Weissmandel taught that one gets “Esther” if they count from the Torah’s first aleph, and “Mordechai” from מור דרור. Funny enough, in a footnote at the very end, Chabad.org admits that they were

not able to duplicate the above results from the same starting places, but they did find “Esther” and “Mordechai” at the cited interval in different locations. Also, some “codes” programs yield a different number of letters for Megilat Esther, such as 13,408 and 12,110. “Esther” and “Mordechai” can be found at these intervals too.

In other words, the code is completely bogus. (Why Chabad.org—otherwise a terrific resource—would publish a story and admit at the end that it is based on something false eludes me.)

True Torah Codes

In his Pardes Rimonim, the great Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) does mention a practice called dilug, along with similar practices like gematria, roshei and sofei tevot, and letter permutations. Of course, he is not at all speaking about the ELS method, which is essentially impossible without a computer, and would have been unknown to the Ramak. The dilug he speaks of is where a word emerges from letter skipping within a verse or short passage—not hundreds of letters apart, or across different chapters, parashas, or even books, as is common in ELS.

For example, there is the old story of the apostate Avner, a former student of the Ramban (which we’ve discussed before). The story ends with the Ramban showing that Avner’s name is embedded within a verse in parashat Ha’azinu; a verse that speaks specifically of God destroying the memory of those who oppose Him, like Avner.* Such small codes—with short skips in verses that actually relate to the topic at hand—may certainly be valid. Still, the Ramban himself points out (in the first gate of Sefer haGeulah) that these kinds of practices must be based on a proper tradition going back to Sinai; a person should not conjure their own gematrias and codes, for in such a way a person will be able to “prove” just about anything.

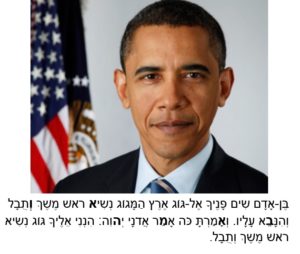

When Barack Obama was elected, many pointed out that his name appears when skipping to every seventh letter from the aleph in the word “nasi” or “president” in the famous apocalyptic passage of Gog u’Magog (Ezekiel 38:2-3). Apparently, Obama did not fulfil his “prophesied” role of bringing the apocalypse.

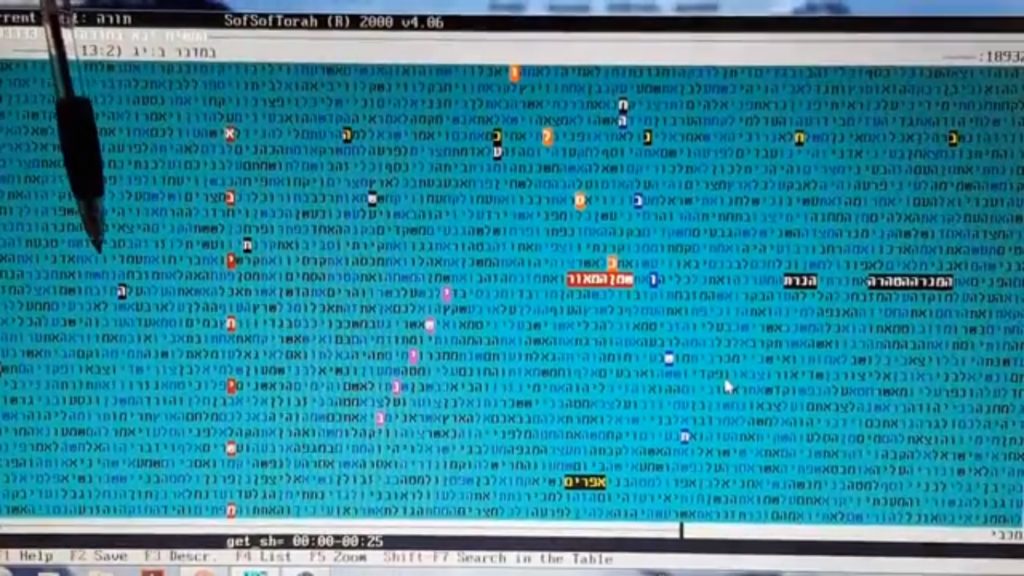

“Bible Codes” abound on YouTube. This video has a code suggesting Mashiach would come during Chanukah of 5778 (ie. December 2017). The same YouTube channel still has videos going back to at least 5774 with codes proving each year to be an auspicious time for Mashiach to come!

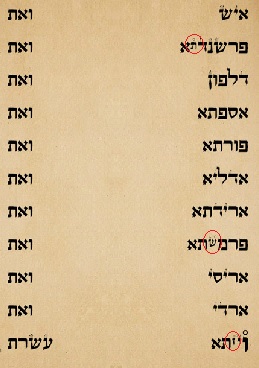

Having debunked one supposed “Purim code”, let’s conclude with a better-known Purim code. This one actually does work quite well and would be valid in the time of the Ramak, too (since it appears within one small passage, requires no computers, and is in context). It was Rabbi Weissmandl who once again first pointed it out. At the end of Megillat Esther, we read how Haman’s ten sons were hanged. The scroll shifts to a unique appearance here in listing the names of the ten sons. Traditionally, three letters in this list are written smaller than normal. Such smaller or larger letters always carry great significance wherever they appear in Scripture. The three here make up תש״ז, as if alluding to the year 5707, corresponding to the year 1946-47.

Amazingly, it was right at that time that the Nuremberg Trials concluded with the hanging of ten of the Nazi elite. In the Scroll itself we read how Esther was asked what to do with the hanged sons of Haman, and she responded: “If it please the king, let it be granted to the Jews that are in Shushan to do tomorrow also according to this day’s decree, and let Haman’s ten sons be hanged upon the gallows.” (9:13) Esther perplexingly asks for the ten sons to be hanged again!

Centuries later, ten of Hitler’s “sons”—some of his closest confidantes and co-conspirators—were hanged on the gallows, forbidden to go by firing squad as would be normal for military men.** And it’s almost as if they were aware of it all: it was reported that among the last words of the despicable Julius Streicher were: “Purimfest 1946”.

The cover of the October 28, 1946 edition of Newsweek. In its coverage of the Nuremberg executions, it states: “Only Julius Streicher went without dignity. He had to be pushed across the floor, wild-eyed and screaming: ‘Heil Hitler!’ Mounting the steps he cried out: ‘And now I go to God.’ He stared at the witnesses facing the gallows and shouted” ‘Purimfest, 1946.’ (Purim is a Jewish feast) … A groan came from inside the scaffold. Critics suggested afterward that Streicher was clumsily hanged and that the rope may have strangled him instead of breaking his neck.”

*The Avner code is actually not an ELS at all. Rather, the Ramban said that the third letter of each word spells “Avner”. These letters are not equidistant.

**The Talmud (Megillah 16a) states that Haman also had a daughter who committed suicide. In 1946, Hermann Göring was sentenced to death as well, but committed suicide the night before. Interestingly, Göring was known to be a cross-dresser. The hangings took place on October 16, 1946, just days after Rosh Hashanah 5707 (תש״ז) and fittingly, on the holiday of Hoshana Rabbah, the “Great Salvation”.

Who is Ahashverosh?

This Wednesday evening marks the start of Purim. The events of Purim, as described in the Book of Esther, take place in the Persian Empire during the time of King Ahashverosh. Who is this king? Is there a historical figure that matches up with what we know of the Biblical Ahashverosh? And when exactly did the Purim story happen?

Ahaseurus and Haman at Esther’s Feast, by Rembrandt

Not long after Jerusalem was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar and the Jews exiled to Babylon, the Babylonian Empire itself fell to the Persians. This was prophesied by Isaiah (45:1), who went so far as to describe the liberating Persian King Cyrus as “mashiach”! In one place (Megillah 12a), the Talmud states that he was obviously not the messiah—though perhaps a potential one—while in another (Rosh Hashanah 3b) it admits that he was “kosher”, and this is why his name (Koresh in Hebrew and Old Persian) is an anagram of kosher.

According to the accepted historical chronology, Cyrus took over the Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE. The Temple was destroyed some five decades earlier in 586 BCE. Our Sages, too, knew that the Babylonian Captivity lasted less than the seventy years prophesied by Jeremiah. They explained that although Cyrus freed the Jews before seventy years, they were unable to actually rebuild the Temple until seventy years had elapsed. In secular chronology, its rebuilding thus took place in 516 BCE. This was in the reign of the next great Persian king, Darius (r. 522-486 BCE). His son and successor was the famous Xerxes I (485-465 BCE), or in Old Persian Khshayarsha, ie. Ahashverosh.

Despite the name, many believe that the Ahashverosh of Purim is not Xerxes I. Scholars have suggested other possibilities, including one of several kings named Artaxerxes. The problem with Artaxerxes is that first of all the name does not match at all, being Artashacha in Old Persian, and second of all the name actually appears elsewhere in Scripture, in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, as Artachshashta (אַרְתַּחְשַׁשְׂתָּא). This is clearly not Ahashverosh (אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ). Having said that, Ezra 6:14 may imply that Artachshashta and Ahashverosh are one and the same. This verse lists Cyrus, then Darius, then Artachshashta, whereas we know from historical sources that following Cyrus was Cambyses, then the more famous Darius, followed by Xerxes I.

The Book of Daniel complicates things further. Daniel speaks of a Darius that conquers Babylon. Yet we know for a fact that it was Cyrus who conquered Babylon. Some scholars therefore say that Daniel is confusing Darius with Cyrus. Others say this “Darius the Mede” conquered Babylon alongside Cyrus, and this version has been accepted by many in the Jewish tradition. Later, Daniel 9:1 says that Darius was a son of Ahashverosh! Hence, some Jewish sources state that the Persian king Darius was the son of Esther. This suggests an entirely different Darius, and historical sources do speak of three Dariuses, the last one being defeated by Alexander the Great.

Perhaps the only way to find the real Ahashverosh is to ignore the other Biblical books and focus solely on Megillat Esther. In this case, the name Ahashverosh only fits Xerxes. There were two Xerxeses in ancient Persia. Xerxes II, though, ruled for just 45 days before being assassinated. That leaves us with Xerxes I. Does the Purim Ahashverosh match the historical Xerxes?

Xerxes the Great

Xerxes was born around 518 BCE to King Darius I and his wife Atossa, who was the daughter of Cyrus the Great. Xerxes was thus a grandson of the first Persian emperor. When Darius I died, his eldest son Artobazan claimed the throne. Xerxes argued that he should be king since he was the son of Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus. Ultimately, it was Xerxes that was crowned, thanks to his mother’s influence. This may be related to the Talmud’s suggestion that Ahashverosh claimed his authority through his wife Vashti, who was the daughter of a previous emperor, while Ahashverosh was just a usurper.

Xerxes immediately solidified his rule and crushed a number of rebellions. He melted down the massive idolatrous statue of Bel, or Marduk, the chief Babylonian god, triggering a number of rebellions by the Babylonians. Xerxes thus removed “king of Babylon” from his official title in an attempt to wipe out any mention of the former Babylon. He remained as “king of Persia and Media, great king, king of kings, and king of nations”.*

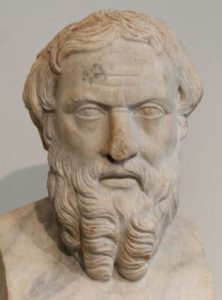

Xerxes is undoubtedly most famous for his massive invasion of Greece in 480 BCE, and particularly the difficulties he experienced at the Battle of Thermopylae (where he faced off against “300” Spartans). Returning home without victory, he focused on large construction projects. The ancient Greek historian (and contemporary of Xerxes) Herodotus (c. 485-425 BCE) notes that Xerxes built a palace in Susa. This is, of course, the Shushan HaBirah, “Susa the Capital” mentioned multiple times in the Megillah. Herodotus further states that Xerxes ruled from his capital in Susa over many provinces “from India to Ethiopia”, just as the Megillah says.

Bust of Herodotus

Herodotus also writes how Xerxes loved women and regularly threw parties where the wine never stopped flowing. Indeed, Megillat Esther speaks of the mishteh, literally “drinking party” that Ahashverosh threw. More specifically, Herodotus wrote how Xerxes returned to Persia from his failed Greek invasion in the “tenth month of his seventh year” and spent a lot of time sulking with his large harem of women. Incredibly, the Megillah also states that “Esther was taken unto king Ahashverosh into his palace in the tenth month, which is the month Tevet, in the seventh year of his reign” (Esther 2:16). This is unlikely to be a coincidence.

More amazing still, among the historical records from the time of Xerxes I that have been found we find the name of a court official named Marduka. Interestingly, this Marduka is given no other titles. It isn’t hard to see the connection to Mordechai, also an untitled official in the court of Ahashverosh.

Xerxes’ reign came to an end in 465 BCE when he was unceremoniously assassinated. His eldest son Darius, who should have succeeded him, was killed, too. This once again may relate to the Jewish tradition of Ahashverosh having a son with Esther called Darius.

However, Xerxes’ son Darius was the child of his queen Amestris, or Amastri, the daughter of a Persian nobleman. Historical sources speak of her in the most negative of terms. Herodotus writes that she buried people alive, and she apparently brutally tortured and mutilated a relative she wanted to punish. She was jealous of her husband’s extramarital affairs, and power-hungry in her own right. Although the name Amestris may sound more similar to the name Esther, Amestris’ character fits the profile of a cruel Queen Vashti quite well (see Megillah 12b).**

A Historical Nightmare

One of the greatest issues in Biblical chronology is the problem of the so-called “missing years”. As mentioned, secular scholarship has 586 BCE (or 587 BCE) as the year of the Temple’s destruction and 516 BCE as its rebuilding. Traditional Jewish dating has around 424 BCE (or 423 or even 421 BCE) for the destruction and 354 BCE (or 349 BCE) for the reconstruction. That’s a discrepancy of some 160 years!

Generally, it is concluded that the Jewish traditional dating is simply wrong, as the Sages did not have access to all the historical and archaeological sources that we have today. As we wrote in the past, the Talmud and other ancient Jewish sources do have occasional historical errors, and this has already been noted by rabbis like the Ibn Ezra and Azariah dei Rossi (c. 1511-1578). Still, the traditional Jewish dating need not be thrown out the door just yet.

In his The Challenge of Jewish History: The Bible, The Greeks, and The Missing 168 Years, Rabbi Alexander Hool makes a compelling case for rethinking the accepted chronology. He brings an impressive amount of evidence suggesting that Alexander the Great did not defeat Darius III, but rather Darius I! After Alexander, the Seleucids did not rule over all of Persia, but only the former Babylonian provinces, while the Persian Empire continued to co-exist alongside the Greek. Interestingly, there is another version of Megillat Esther (sometimes called the Apocryphal Book of Esther) which may support the theory. While the apocryphal version is certainly a later edition and not the authentic one, it still provides some additional information which may be useful. This Book of Esther actually says Haman was a Macedonian, like Alexander the Great, which fits neatly with Hool’s theory. Having said that, Hool’s theory is very difficult to accept, and would require rewriting a tremendous amount of history while ignoring large chunks of opposing evidence. Elsewhere, though, he may be right on point.

Hool suggests that Cyrus and the mysterious “Darius the Mede” are one and the same person, with evidence showing “Darius” is a title rather than a proper name. He argues that “Ahashverosh” may be a title, too, and concludes that the Ahashverosh of Purim is none other than Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE), the son of Cyrus. This suggestion fits well with the chronology presented in Jewish sources (especially Seder Olam) and with the Tanakh (where, for example, Darius I is the son of Ahashverosh in the Book of Daniel). It also fits with the description of Cambyses given by Herodotus, who says Cambyses was a madman with wild mood swings, much like the Ahashverosh in the Megillah. The timing is excellent, too, fitting inside the seventy year period before the Second Temple was rebuilt and while the Jews were still in exile mode.

Identifying Cambyses with Ahashverosh opens up a host of other problems though. The Megillah has Ahashverosh reigning for at least a dozen years, whereas Cambyses only reigned for about seven and a half. The other details that we know of Cambyses’ life and love interests do not match Ahashverosh either. Point for point, it seems that Xerxes I still fits the bill of Ahashverosh much better than anyone else, despite the chronological mess.

At the end of the day, history before the Common Era is so frustratingly blurry that it is difficult to conclude much with certainty. Without a doubt, there are historical errors and miscalculations in both secular scholarship and in ancient Jewish sources. It seems the identity of Ahashverosh and the exact chronology between the destruction of the First and Second Temples is one mystery that can’t be solved at the moment.

*Perhaps Xerxes’ father Darius is the one called “Darius the Mede” (being unrelated to Cyrus). This makes more sense chronologically if Daniel was one of the original Jewish exiles, as the Tanakh suggests. The Book of Daniel should have said that Ahashverosh was the son of Darius, and not vice versa. In fact, the Talmud (Megillah 12a) admits that Daniel erred in some chronological details. This may be why the Book of Daniel is not always considered an authoritative prophetic book, and is included in the Ketuvim, not the Nevi’im. In Jewish tradition, Daniel is typically excluded from the list of official prophets.

**The Talmud suggests that Vashti was the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar (Megillah 10b) or Belshazzar (Megillah 12b), while Ahashverosh was only the son of their stable-master. This makes little sense chronologically or historically. Scholars have pointed out that this extra-Biblical suggestion in the Talmud may have been adapted from the popular Persian story of the king Ardashir I (180-242 CE), which would have been well-known in Talmudic times.