At the end of this week’s parasha, Chukat, the Torah tells us about the war between the Israelites and the Moabites. The Torah says woe to “the people of Chemosh” who will be lost and destroyed (Numbers 21:29). Chemosh is the name of the chief deity of the Moabites. It is interesting that the Torah names this idol, considering that there’s a clear mitzvah to completely obliterate the names of false idols and never so much as mention their names! (Exodus 23:13) The Talmud explains that if a name of a certain idol is recorded in the Torah, then we are obviously permitted to pronounce it in the course of learning and reading the Torah (Sanhedrin 63b).

Others comment that the prohibition of mentioning idol names is only if actually employing the names like idolaters might, such as in the form of worship or reverance, or by swearing on an idol’s name for business deals or in a courthouse. (See the Rambam’s Avodat Kochavim 5:10-11, and the Ramban on Exodus 23:13). It would even be forbidden for a Jew to make a gentile swear in the name of his false god, or for a Jew to tell a fellow Jew to meet him by the statue of a certain idol. That said, it is not prohibited to mention the names of idols for valid educational purposes and warnings about idolatry. (If you can’t clearly name and identify the idols, it might be difficult to educate people on avoiding them!)

The Haftarah for this week’s parasha builds on the same theme, with the hero Yiftach delivering a long historical speech, and telling the Moabites: “that which Chemosh your god gives you to possess, you may possess; and all that which יהוה [YHWH], our God, has driven out from before us, we shall possess!” (Judges 11:24) The Haftarah makes a point to specifically name Hashem multiple times, highlighting the greatness of YHWH over the false idol Chemosh. This reminds us of the mitzvah mentioned countless times throughout the Tanakh that the Jewish people should spread the name of God far and wide, to “call in God’s Name”—a practice that goes all the way back to Abraham himself, who “planted an eshel tree at Beer-Sheva, and from there called in the name of YHWH, the Everlasting God.” (Genesis 21:33)

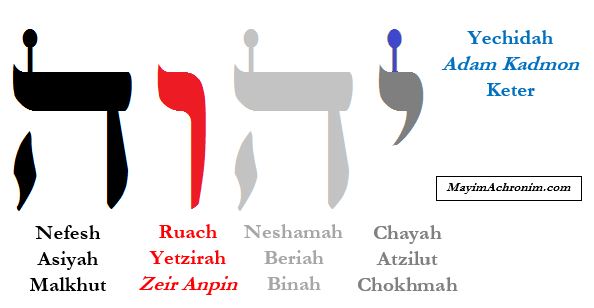

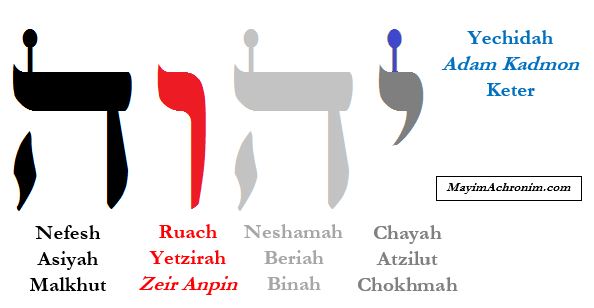

The parts of God’s Ineffable Name (the four letters and the “crown” atop the Yud) correspond to the five levels of soul, the five mystical dimensions or olamot, the five groupings or “faces” of the Sefirot, as well as the five books of the Torah.

This begs the question: what does it mean to “call in God’s Name”? And are we even allowed to pronounce the various names of God? It is common knowledge that we don’t pronounce the Ineffable Name, YHWH, but what of all the other titles for God, such as Elohim, Adonai, and El Shaddai? Can we utter these names outside of prayers and Torah readings?

The Evolution of Ineffable

Originally, the Ineffable Name of God was not “Ineffable” at all. In Biblical times, it was used freely by Israelites, and frequently embedded within people’s names (usually without the final letter Hei) like Eliyahu, Yeshayahu, Yirmiyahu, Yehudah, Yehoshafat, Yehoyada, and so on. In the Book of Ruth we read of the common greeting YHWH imachem, “God be with you”, to which the recipient would reply: yevarekhekha YHWH, “God bless you!” (Ruth 2:4) Even today there is a fairly widespread custom to say these phrases when a person gets called up to the Torah, before reciting the blessings, except that now YHWH is typically replaced with “Hashem”.

Meanwhile, the Torah commands the kohanim to pronounce the Name when blessing the congregation: “And they shall place My Name upon the Children of Israel, and I will bless them!” (Numbers 6:27) The Name itself is the conduit of God’s special blessing. We still do the priestly blessing today, but without the actual pronunciation of God’s Name, in which place the kohanim say Adonai or Adonoi. It makes one wonder if the blessing still has the same effect if the kohanim are not actually placing God’s Name “upon the Children of Israel” as the Torah commands. So, how did Adonai come to replace YHWH?

Clearly, the Tanakh does not prohibit pronouncing God’s Name, and only warns against pronouncing God’s Name in vain, which is one of the Ten Commandments. The Mishnah (Sanhedrin 10:1) presents a minority opinion that someone who pronounces God’s Name has no share in the World to Come. Again, this must be referring to someone who pronounces the Name in vain, since we know the Name was known and used even in Talmudic times. In one place (Avodah Zarah 18a), the Talmud speculates on the deeper reasons for why Rabbi Chanania ben Teradion was executed by the Romans, with one opinion suggests he may have been too careless with pronouncing the Ineffable Name in public, and should have been more discrete. In another place (Kiddushin 71a), the Talmud says the Sages would teach the Ineffable Name once or twice in seven years. It is here that the Talmud affirms to avoid pronouncing the Ineffable Name with its actual four letters, and instead to say “Adonai”.

The earliest origin of using Adonai in reference to God is Genesis 18:3, when God appears to Abraham. Three angels then show up, and Abraham says: “Adonai, if it please you, do not go on past your servant!” The classic question here is: to whom does Adonai refer? Was Abraham speaking to God, or to the three angels that suddenly showed up? At first glance, the latter makes more sense, and Abraham was referring to the three mysterious figures as Adonai, “my lords”, in the plural. Hospitable Abraham was asking the three to stick around and not pass him by.

Rabbinic tradition, however, concludes that Adonai refers to Hashem here, and Abraham was telling God not to “pass by” or leave while he goes off to assist the three unannounced guests. This is where Adonai is first linked to YHWH, and the fact that “Adonai” is plural is not an issue, the same way “Elohim” is plural. The plurality is a form of respect, as is still found in many languages (including Russian and French) to refer to an elder or authority figure. It used to be the case in English, too, where “you” used to be the plural and “thou” the singular. Over time, the respectful plural “you” became the standard singular, while the informal “thou” disappeared.

Interestingly, while Adonai was instituted in order to avoid pronouncing the Ineffable Name in vain, over time Adonai itself became a holy name that shouldn’t be said in vain! Today, it has become common for people to instead say Hashem, “The Name”. Sometimes people (especially musicians) will say “Amonai” instead of Adonai—but this is highly problematic because Amon was the name of a chief deity of the ancient Egyptians! Other times, people will refer to the Ineffable Name by saying the actual letters sequentially, as Yud-Hei-Vav-Hei. This is perfectly appropriate, and was the practice of the Arizal (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria, 1534-1572). Yet, as expected, people tend to add extra (unnecessary) fences and now many will say Yud-Kei-Vav-Kei.

In Sha’ar haMitzvot (on parashat Shemot), the Arizal’s primary disciple Rabbi Chaim Vital notes how “My master of blessed memory [the Arizal] told me that one should not pronounce the four letters of God’s Name unless he does so through a milui, as follows: Yud-Hei-Vav-Hei”. (אמר לי מורי זלה”ה כי אמיתות פי’ דבר זה הוא שלא יקרא ד’ אותיות ההוי”ה ככתבן בלי מילוי אבל אם גם יקראנו במילוי כזה יו”ד ה”י וי”ו ה”י.) Rabbi Vital goes on to explain that the Arizal was careful to avoid pronouncing the names of certain angels, so Rabbi Vital asked him: “If we are allowed to always pronounce names of God like Adonai and Elohim, why would we be forbidden from pronouncing names of created angels?” (ופעם אחת שאלתי למורי זלה”ה כי הרי שמות אדני ואלהים וכיוצא אנו מזכירים אותם תמיד ואם כן למה אסור להזכיר שמות המלאכים הנבראים.) In other words, the names of angels are obviously less holy than names of God, so why are we careful with the former and not the latter? The Arizal explained that names of God are pure and can never receive any impurity, while names of angels can be manipulated, misused, and attract impurity. Hence, we can use names of God freely, but we should be more careful with the names of certain angels. The passage concludes by saying that, of course, when it comes to the names of common angels which have also become people’s names (examples given are Michael and Gabriel), these are permitted to use freely and as necessary.

We learn from this that it is not necessary to replace Elohim with Elokim, like many today do, or to fear using titles like Adonai. Similarly, names like El Shaddai are not ineffable, and can be pronounced as is, assuming it is done in a respectful manner or in the course of education or recitation of verses (so there is no need to say “Shakkai” in place of “Shaddai”). In fact, it is actually inappropriate to do so: Over the years, I’ve spoken to many recent baalei teshuva, converts, new students, and the like, and oftentimes these well-meaning people do not realize that Shakkai or Elokim are not genuine names of God at all. Because they heard others speak this way, they were unaware of the true name of God—and this is highly problematic and unfortunate.

For God’s sake, we really must use the appropriate titles, and “call in God’s Name” as the Torah reminds us many times. Our mission is to spread Godliness and awareness of Hashem far and wide, and to do so we must use the proper names of God, or else we spread confusion and misinformation. This sentiment was echoed in a detailed analysis of the issue by Rabbi Yitzchak Ratzavi in his Olat Yitzchak (II, 74 on Orach Chaim). There, he argues that such distortions of God’s names were never used by our Sages or referenced in any early Jewish holy texts, and that this is a recent phenomenon which actually denigrates God’s holy names!

דע שהזכרת שם אלקים בקו״ף במקום ה״א כפי שנפוץ בזמנינו, וכן קל במקום אל, קה במקום יה [שק״י במקום שדי, צבקות בשם צבעות] וכיו״ב לא נזכר שמץ מנהו בדברי חז״ל והקדמונים… ואדרבה י״ל שהוא גנאי לכנות כך לשמו ית׳

Know that mentioning “Elokim” with a kuf instead of a hei, as is common in our days, and similarly “Kel” instead of “El”, “Kah” instead of “Yah”, “Shakkai” instead of “Shaddai”, “Tzvakot” instead of “Tzva’ot”, and the like – these are not mentioned at all in the words of our Sages of blessed memory or the early rabbis… on the contrary, one could say that it is a denigration of God’s Names!

One thing that Rabbi Ratzavi points out in his historical examination is that these name-distortions were innovated by Ashkenazim who sought more stringencies, but were unheard of in the Mizrachi world, including the Yemenite community from which he hails. Indeed, Sephardic sources have always been far more balanced and logical in this regard, and truer to the Torah’s call for Jews to invoke God’s proper names. Rav Ovadia Yosef, for instance, was known to use the proper names of God in reciting verses both while learning and teaching.

To summarize: the Tetragrammaton YHWH is not to be pronounced (and few know the proper pronunciation anyway!) Adonai is the proper replacement when reciting verses—and does have its own status as a genuine name of God as well, so should not be misused. In colloquial speech, Adonai is replaced by Hashem. Other titles and appellations of God may be used, too, respectfully and not in vain, of course. These include six more names of God that are considered especially holy and, like the Tetragrammaton, are forbidden from being erased if written down: El, Elo’ah, Elohim, Elohai, Shaddai, and Tzva’ot (see Rambam’s Yesodei HaTorah 6:2). On the point of “not in vain”: saying names of God while reciting verses during prayers or Torah study (including Talmud study) is obviously not in vain, nor is it in vain in the course of teaching Torah or in the context of a shiur. It is also not in vain when singing verses from Psalms, various piyyutim and Shabbat zemirot (and I would even add: kosher Hebrew songs by modern-day artists), since it is a legitimate shevach or praise of God, sung with positive and spiritual intentions. Plus, they help to spread knowledge of God’s names throughout the world, as the Torah instructs us to do.

On that note, everyone agrees that we are now in Ikvot haMashiach, the “Footsteps of the Messiah”, and are gradually transitioning into the long-awaited Olam haBa, the “World to Come”. It is therefore worth noting that the Talmud (Pesachim 50a) states in this current world, we pronounce the Ineffable Name as Adonai, but in the World to Come, we will go back to properly pronouncing the four letters YHWH as in ancient times. In fact, the Talmud (Bava Batra 75b) says that in the future, three will be called by the Ineffable Name: the four holy letters will be appended to the name of the holy city of Jerusalem, and to the name of Mashiach, and to all of the tzadikim that will merit to be alive then:

עֲתִידִין צַדִּיקִים שֶׁנִּקְרָאִין עַל שְׁמוֹ שֶׁל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כֹּל הַנִּקְרָא בִשְׁמִי וְלִכְבוֹדִי בְּרָאתִיו, יְצַרְתִּיו אַף עֲשִׂיתִיו״. וְאָמַר רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: שְׁלֹשָׁה נִקְרְאוּ עַל שְׁמוֹ שֶׁל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: צַדִּיקִים, וּמָשִׁיחַ, וִירוּשָׁלִַים. צַדִּיקִים – הָא דַּאֲמַרַן. מָשִׁיחַ – דִּכְתִיב: ״וְזֶה שְּׁמוֹ אֲשֶׁר יִקְרְאוֹ ה׳ צִדְקֵנוּ״. יְרוּשָׁלַיִם – דִּכְתִיב: ״סָבִיב שְׁמֹנָה עָשָׂר אָלֶף, וְשֵׁם הָעִיר מִיּוֹם ה׳ שָׁמָּה״…

In the future, the righteous will be called by the Name of the Holy One, Blessed be He; as it is stated: “Every one that is called by My Name, and whom I have created for My glory, I have formed him, and I have made him.” (Isaiah 43:7) And Rabbi Shmuel bar Nachmani says that Rabbi Yochanan says: Three will be called by the name of the Holy One, Blessed be He, and they are: The righteous, and Mashiach, and Jerusalem. The righteous, as already explained. Mashiach, as it is written: “And this is his name whereby he shall be called: YHWH-Tzidkenu.” (Jeremiah 23:6) Jerusalem, as it is written: “It shall be eighteen thousand reeds round about. And the name of the city from that day shall be YHWH-Shammah.” (Ezekiel 48:35)

One could therefore argue that it may be the task of Mashiach himself to re-teach the world the true pronunciation of God’s Ineffable Name, and to restore the primordial task of “calling in God’s Name” wherever we go. Indeed, right after describing Mashiach in chapter 11, the prophet Yeshayahu tells us that in that future era, “you shall say: thank YHWH, call in His Name, publicize His deeds among the peoples; keep it in remembrance, for His Name is exalted!” (Isaiah 12:4) And the prophet Tzfanyah adds: “For then I will make the peoples pure of speech so that they will all call YHWH by name, to serve Him together.” (Zephaniah 3:9)

May we merit to see that day very soon!