This week’s parasha, Terumah, begins the Torah’s long and detailed descriptions of the Mishkan, or Tabernacle. More than just a “mobile sanctuary”, the Mishkan was constructed as a microcosm of the entire universe. The Midrash points out how each of the Mishkan’s components corresponded to an act of Creation (Midrash Aggadah on Exodus 38):

First in Genesis was “Heaven and Earth”, and this was symbolized by the Two Tablets in the Ark of the Covenant contained within the Mishkan’s “Holy of Holies”. Of the Ten Commandments, the first half deal with mitzvot between man and God, while the second half are between man and fellow. (The fifth, honouring parents, is thought to be a bit of both.) So, we can see how one Tablet would correspond to “Heaven” and the other Tablet to “Earth”!

Next on the list is the Rakia, often poorly translated as “Firmament”. This was created on the Second Day to separate “between the waters” above and below, ie. between the Heavens and the Earth. The Midrash states that in the Mishkan it corresponded to the parokhet, the curtain that separated the Holy of Holies from the rest of the Tabernacle. Interestingly, in describing the “Seven Heavens”, the Talmud (Chagigah 12b) teaches that the first and lowest of the Heavens—right beneath the Rakia—is called Vilon, literally meaning “curtain” in Latin (velum).

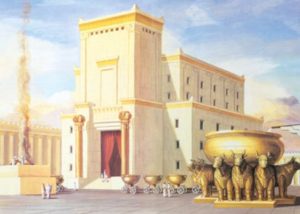

On the Third Day, God “gathered the waters” to form the oceans, and this paralleled the Mishkan’s kior, the copper laver where the kohanim washed. Later, King Solomon built a much larger “Molten Sea” in front of Jerusalem’s Temple, supported by a dozen statues of oxen (the connection between this Molten Sea and mathematical pi was discussed previously here). Also on the Third Day, God formed the lands and made them flourish with grasses and plants. Similarly, the Mishkan had the Shulchan with ever-fresh loaves of bread.

On Day Four, God created the luminaries, of which there are seven visible to the naked eye: sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The Seven Luminaries play a big role in ancient texts, both Jewish and non-Jewish. In fact, in many cultures and languages, the seven days of the week are named after them. In English: Saturday, Sunday and Monday are named after Saturn, sun, and moon. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday are named after the Norse gods Tiw, Woden (or Odin), Thor, and Frigg (or Frei), corresponding to Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus. The connection is easier to see in the French names for these days: mardi, mercredi, jeudi, and vendredi. The Midrash explains that in the Mishkan, the Seven Luminaries were represented by, of course, the luminous Menorah with its seven branches.

On the Fifth Day, God created winged animals, and corresponding to these are the Kruvim, the winged Cherubs on the Ark of the Covenant. The Midrash doesn’t say anything about fish, which were also created on the Fifth Day. Intriguingly, the Mishkan (and later Temple) had a variety of offerings including fruits, grains, and breads, birds and land animals—but no fish! However, the special blue tekhelet dye that was used in the Mishkan fabrics and priestly garments does come from sea snails, so perhaps we can add that to the list in the Midrash.

The main creation of Day Six was Adam. The Midrash says that God brought Adam into the Garden of Eden on that same day, leading the first human into that special holy place. Similarly, in the Mishkan we had Aharon serve as kohen gadol, representing Adam, and entering the Holy of Holies, the Mishkan’s special “Garden of Eden”. The Midrash adds that Aharon was greater than Adam, since Adam sinned in the Garden, but Aharon atoned for sin in the Holy of Holies. This further helps us understand the true role of the kohen: to restore some of the world’s lost holy light.

After Adam consumed of the Forbidden Fruit, God called out ayekah (איכה), “where are you?” (Genesis 3:9) As explored in the past, this word can be broken down into ayeh koh (איה כ״ה), “where is the 25?” The 25 alludes to the 25th word of the Torah which is ohr, “light”. So, God was really asking “Where is the light of Creation?” for Adam and Eve caused that light to be lost. All of Israel is called to be a light unto the nations, and restore that light to the world. Within Israel, the kohanim in particular had to take the lead. And they would bless the people of Israel to help them accomplish this task, as the Torah states: koh tevarkhu et bnei Israel (Numbers 6:23). In fact, the kohen himself is a koh-en, a bringer of that hidden light. The Midrash actually goes on to say that, really, all of Israel are likened to kohanim, and will all become kohanim in the future, as it is written, “You shall all be called ‘priests of God’ [kohanei Hashem], and ‘servants of God’ shall be said of you; you shall enjoy the wealth of nations and revel in their honour.” (Isaiah 61:6)

And Hashem promises many more rewards: in the merit of the parokhet that the Israelites made corresponding to the Rakia, God promises to make us all glow like the Heavens, as it says, “And the wise ones shall glow like the glow [zohar] of the Rakia…” (Daniel 12:3) In the merit of the Shulchan, God promises to bless the land and its fruits (Leviticus 26:4). In the merit of the Menorah, God promises to bring upon us the light of the Shekhinah, and magnify the light of the luminaries, as it says in Isaiah 30:26 that “the light of the moon shall become like the light of the sun, and the light of the sun shall become sevenfold…” Finally, in the merit of the Cherubs that correspond to the flying creatures, God will end the exile and fly us all back to Israel “like doves to their cotes” (Isaiah 60:8). This would have been very hard to imagine for most of history, until recent decades, as we can now literally fly to the Holy Land!

Thankfully, we have already seen these promises begin to be fulfilled right before our eyes. We are nearing the finish line, and we will soon see the return of Hashem’s Sanctuary, together with all of its holy vessels and the Ark of the Covenant, in an everlasting edifice, at its rightful place in the Holy Land.