This week’s parasha, Bechukotai, contains an infamous list of curses that could befall the Jewish people, has v’shalom, if they stray from God’s ways. Jewish history shows that we have indeed experienced such tragic curses over the millennia every so often, and not just in the distant past but recently on October 7. As difficult and inexplicable such events may be, we have to keep in mind that while they come at the hands of various political entities and ethnoreligious groups, ultimately the source of the pain is God Himself. As the parasha tells us, the tragedies are both an unfortunate retribution for our transgressions, and a wake-up call to be better.

‘Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem’ by Francesco Hayez (1867)

One of the first such unspeakable catastrophes took place roughly twenty-five centuries ago, at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians. They massacred tens of thousands of Jews, enslaved and exiled many more, destroyed Jerusalem, and burned down the Holy Temple. Yet, the prophet Jeremiah quotes Hashem saying Nebuchadnezzar is His “servant” (Jeremiah 43:10), His instrument in bringing about punishment. The sad reality is that history’s wicked tormentors were tools of God. They would not arise had we not deserved it. We read in Isaiah 45:7 that “I am God, and there is no other; I form light and create darkness; I make peace and create evil, I am Hashem, doing all of these things.” If it is God’s Will to do such things, what does that make of the free will of the human tormentors?

Our Sages teach that when a person ascends to a high political position, and holds the lives of many in their hands, God limits that person’s free will. God will occasionally “harden their hearts” (as He did with Pharaoh) and steer their choices if necessary. This was described long ago by King Solomon when he said “Like channeled water is the heart of a king in God’s Hand; He directs it wherever He wishes.” (Proverbs 21:1) The Talmud cites this verse in saying that each person should pray “for a good king”, meaning we should pray that God direct political leaders to act justly and kindly with the populace (Berakhot 55a). God can cause a political leader to do more good, or to bring about punishment. And this takes us right back to October 7:

Everyone is puzzled by the fact that the Israeli government missed all the warning signs, was paralyzed by inaction on the morning of, and seemingly allowed the October 7 massacre to happen. It appears to be totally inexplicable and, not surprisingly, has given rise to multiple conspiracy theories. Did the government deliberately allow the massacre to happen? Did they want a serious external conflict to end the civil unrest that was taking place in the months prior to October 7? Did they have a hand in planning the attack? Did they purposely keep the border unguarded, or move military units away from the border, or give an abnormally large number of soldiers holiday vacations, or jam communication channels, or change permits to move the Nova festival from its original location right to the Gaza border? The theories are numerous, each more sinister than the next. Personally, I find them hard to believe, and although I am no fan of the government, it feels absurd to suggest that anyone could deliberately allow something like this to happen to their own people.

But then I was reading Jeremiah—the same Jeremiah that refers to Nebuchadnezzar as God’s servant, and the same Jeremiah from whom we read this week’s Haftarah. We find something quite amazing in the Book of Jeremiah: it is the one place in the Tanakh that describes a family called “Netanyahu”. (Another is briefly mentioned in a list in I Chronicles 25:12.) Jeremiah first speaks of a righteous court official named Yehudi ben Netanyahu (36:14). Yehudi delivers a scroll bearing Jeremiah’s gloomy prophecy to the king, and reads it before him. Judea’s King Yehoyakim refuses to heed the warning and thinks he is safe from the Babylonians. He scoffs and burns the prophetic scroll of Jeremiah. We hear no more of Yehudi ben Netanyahu after this.

We then read how Jeremiah’s prophecy was tragically fulfilled. The Babylonian armies arrived, destroying Jerusalem and the Temple and starting the grim period of the Babylonian Captivity. However, the Babylonians did not expel all the Jews from the Holy Land, and even allowed the Jews some autonomy to continue governing themselves. They appointed a Jewish leader named Gedaliah ben Ahikam as governor of Judea. Gedaliah reassured the remaining Jews that everything would be okay; to stay in the Holy Land and rebuild.

Here we are introduced to another Jewish leader, called Ishmael ben Netanyahu (40:8). A descendant of the Davidic monarchy, he had dreams of becoming king and making himself the undisputed leader of Israel. Gedaliah, of course, stood in his way. Ishmael made a secret alliance with the king of Ammon (same place as today’s Amman, capital of the Palestinian state of “Jordan”) to assassinate Gedaliah. Gedaliah was warned of Ishmael’s sinister plans, but dismissed the rumours, thinking no self-respecting Jew could ever stoop so low.

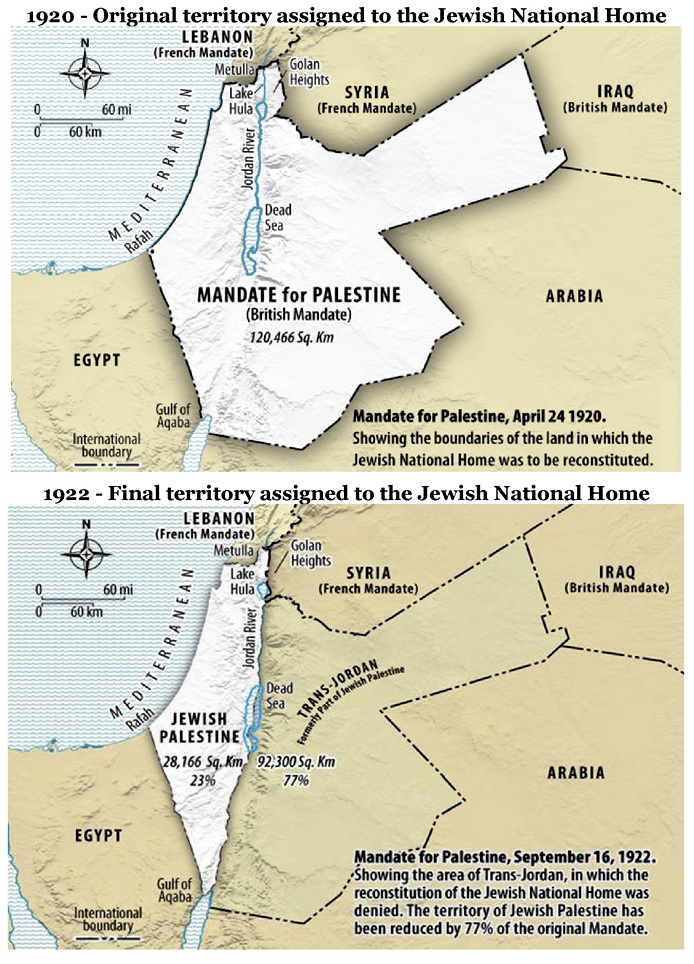

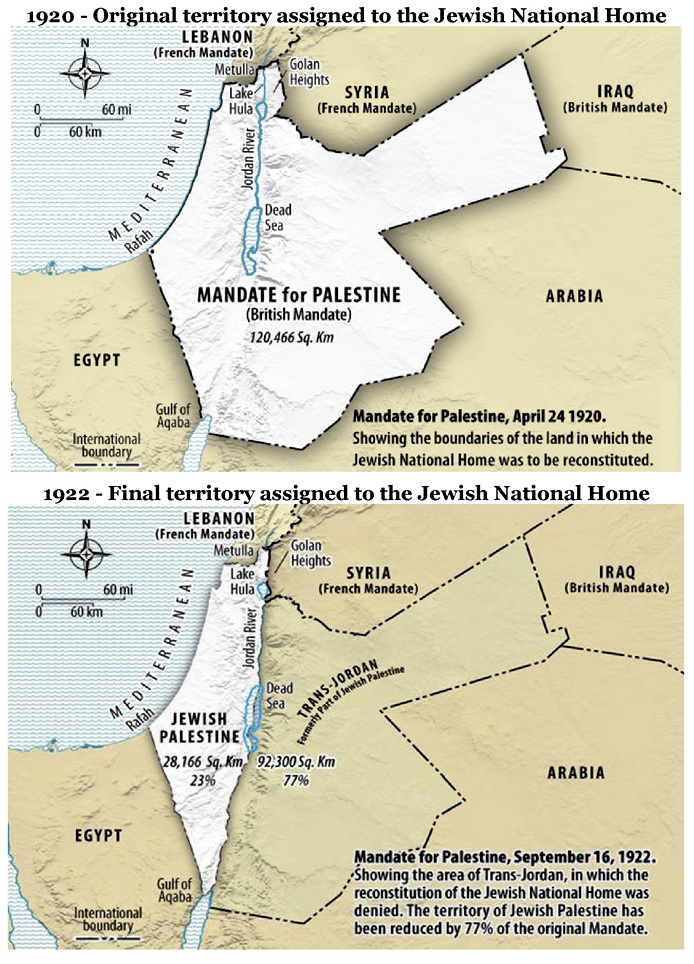

Although the entire British Mandate for Palestine was originally promised to the Jewish people, the British suddenly gave away more than two-thirds to the Arabs to form a new Palestinian state now called “Jordan”. (Credit: Eli E. Hertz)

But then, “in the seventh month” (Tishrei), Gedaliah was having a holiday feast and Ishmael joined him for the yom tov meal (41:1). Wicked Ishmael suddenly struck down Gedaliah “and all the Jews who were with him” (41:3). The next day, pilgrims “came from Shechem, Shiloh, and Samaria” to bring holiday offerings. Ishmael came out to greet them and invited them into town before turning on them and slaughtering them, too (41:7). Ishmael threw all the corpses into a cistern. He didn’t stop there:

Ishmael carried off all the rest of the people who were in Mizpah, including the daughters of the king—all the people left in Mizpah, over whom Nebuzaradan, the chief of the guards, had appointed Gedaliah son of Ahikam. Ishmael son of Netanyah carried them off, and set out to cross over to the Ammonites. (41:10)

Ishmael took hostages and fled back to Ammon. A Judean general named Yochanan ben Kareach finally figured out what’s going on and chased after Ishmael with his men, managing to free the hostages. Ishmael, however, escaped and we don’t know what happened to him afterwards.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the frightened and traumatized Judeans feared the Babylonians would come back to punish them for the death of the Babylon-appointed governor Gedaliah. Despite Jeremiah’s protests and assurances that all would be fine, the remnant of Jews decided to flee to Egypt. The result of Ishmael’s treachery was that the Holy Land lost its last Jews, along with its semi-autonomous Jewish government. The last traces of the Kingdom of Judea were officially obliterated.

For this terrible tragedy, we still observe the “Fast of Gedaliah” today every year immediately following Rosh Hashanah. Though the Tanakh doesn’t say exactly which holiday it was, according to tradition the Gedaliah massacre occurred on Rosh Hashanah. Since we don’t fast on holidays, the fast is observed on the third of Tishrei. However, a careful reading of the Tanakh suggests that the holiday may have been Sukkot, hence the pilgrims that came the following day to bring offerings. Altogether, the narrative is eerily similar to what we experienced last Sukkot in Tishrei, when Ishmaelites came into the land and slaughtered Jews peacefully celebrating a holiday, while taking other Jews hostage.

Strangely, the villain in the Jeremiah narrative (also recounted in II Kings 25) is a power-hungry Jewish leader named Ishmael ben Netanyahu. It would be another millennium before an Ishmaelite by the name of Muhammad would arise, and henceforth “Ishmael” would always be associated with the Muslims. If this episode in Tanakh is not only historical, but prophetic, I wonder what it might mean for all of us today.

I am reminded of the fact that our own Netanyahu was all too kind to the Ishmaelites, giving record-high work permits to Gazans to enter Israel (the Bennett government gave 10,000 before Netanyahu came back to power last year and doubled it to 20,000), transferring Qatari suitcases of cash to support them, and refusing pre-emptive strikes when warned by military officials. The same Netanyahu has yet to fulfil a single objective in the current war. Nearly eight months later, most of Hamas’ tunnel infrastructure is still in place, their leaders still at large, rockets still being fired on Israel, and worst of all, a multitude of hostages still in captivity. The government of Israel is paralyzed, the Knesset remains a circus of corruption (on both sides left and right, secular and “religious”), and “there is no one to rely on but our Father in Heaven.” (Sotah 49b)

Will today’s Netanyahu be more like the righteous Yehudi ben Netanyahu—who supported Jeremiah the Prophet and sought to lead people towards truth and repentance, while confronting the corrupt government of Yehoyakim—or is he more like Ishmael ben Netanyahu, a power-hungry manipulator and a collaborator with Israel’s enemies, a facilitator of Jewish massacres? Will he go down in history as a real “Yehudi”, or as an imposter “Ishmael”? I hope time will prove the former to be the case, but I fear the reality is fast-approaching the latter. If Benjamin Netanyahu does not make some dramatic changes for himself and his country, he may well end up like Ishmael ben Netanyahu long before him; shamefully fleeing his country, remembered for centuries thereafter as a villain.

Whatever happens, Jeremiah in this week’s Haftarah reminds us of a critical principle never to lose sight of: “Cursed is the man who trusts in man… Blessed is the man who trusts in God; and God shall be his security.” (17:5-7)