Abraham’s Journey to Canaan, by Jozsef Molnar (1850)

After two parashas that span the first two millennia of civilization, the Torah shifts its focus to the origins of Israel and the Jewish people starting with, of course, Abraham. Abraham is probably most famous for something that he actually isn’t: being the first monotheist. Noah was a monotheist long before Abraham, as was Noah’s son Shem, who was already a priest of the one Supreme God (El Elyon, as in Genesis 14:18). In Jewish tradition, it is said that Shem established the first yeshiva, and the patriarchs studied there. Was Abraham the first monotheist? No, but he is described as being the first person to actively preach monotheism to the world. He took it upon himself to crusade against idolatry—and the immoral behaviours that went with it.

Some of our Sages also state that Abraham invented the concept of a positive mitzvah. This means drawing closer to God not by abstinence and asceticism but through acts of kindness and the performance of physical actions. For this reason, the gematria of “Abraham” (אברהם) is 248, equal to the number of positive commandments in the Torah. Not surprisingly, Abraham is well-known for his legendary hospitality, his great compassion, and his ceaseless efforts on behalf of his fellow man.

Jewish tradition describes Abraham’s house as having a front door on each side so that guests wouldn’t have to look for the entrance. Meals were always on the house, as long as the guest was willing to thank God for it. Of his compassion, we read in the Torah how Abraham questioned God before the destruction of Sodom, seeking to exonerate the people despite their cruelty (Genesis 18). In this week’s parasha, Lech Lecha, we read of all the “souls that they had made” (Genesis 12:5), the countless people that Abraham and Sarah inspired and brought closer to God. In fact, the Meshekh Chokhmah (of Rabbi Meir Simcha of Dvinsk) on Genesis 33:18 states that Abraham later migrated to Egypt specifically because it was the capital of idolatry and impurity at the time, and Abraham wished to bring some light to that dark place.

What else do we know about Abraham? Extra-Biblical texts reveal some intriguing details in the life of Judaism’s first patriarch.

Discovering God

There are three major opinions as to when Abraham came to know God. The Talmud (Nedarim 32a) holds that he first recognized his Creator when he was three years old. This is deduced from Genesis 26:5, where God says Abraham had “listened to My voice”, ekev asher shama Avraham b’koli. The term “ekev” (עקב) has a numerical value of 172, and since we know Abraham lived 175 years, we learn that Abraham had listened to God’s voice for 172 of them, starting at age 3.

The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204), meanwhile, writes in his Mishneh Torah that Abraham came to know God at age 40 (Hilkhot Avodat Kochavim 1:3). A more commonly-held view is that Abraham came to know God at age 52. This is based on the Talmudic statement that history is divided into three eras: the first 2000 years being the era of “chaos”, the next 2000 years being the era of Torah, and the final 2000 years being the era of Mashiach (Avodah Zarah 9a). Since we know that Abraham was born in the Hebrew year 1948, and the era of Torah started in the year 2000, Abraham must have been 52 when he came to know God.

One way to reconcile these three opinions is as follows: Abraham first realized there must be one God when he was three years old. By age 40, he was ready to begin his life’s work, and set forth in preaching his message. This got him into a lot of trouble, for which he was imprisoned, and ultimately sentenced to death. The Talmud (Bava Batra 91a) clarifies that he was imprisoned for 10 years. Then came the day of his execution. Abraham was thrown into the flames of Ur Kasdim when he was 52, and at this point God actually revealed Himself to Abraham for the first time, miraculously saving him from death. Therefore, there are those who say it wasn’t God who chose Abraham, but Abraham who chose God.

Abraham was already preaching long before he received any kind of prophecy or communication from Hashem. He logically deduced there must be one Creator to this world, and recognized the folly of idolatry on his own. He then took it upon himself to teach this truth, despite never having “heard” anything from God, or being summoned to do so. God chose him precisely because of this incredible initiative. We learn this explicitly from Genesis 18:19, where God says:

For I have known him, that he commands his children and his household after him, that they should keep the way of God, to do righteousness and justice; therefore God brings upon Abraham that which He has spoken of him.

God chose Abraham because he was already teaching others to be more Godly! At age 52, the God that Abraham had been preaching about for so long finally revealed Himself, in miraculous fashion. This sets off a new 2000-year era, that of Torah and prophecy, spanning from Abraham until the times of Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi, who compiled the Mishnah, thus putting the Oral Torah in writing for the first time.

Abraham the Kabbalist

The Talmud (Bava Batra 91a) states that Abraham was world-famous for being an unparalleled astrologer and healer. According to tradition, he was also a great mystic. It is believed that he authored, or in some other way originated, Sefer Yetzirah, the “Book of Formation”, one of the most ancient Kabbalistic text. The book explains how God fashioned the universe through the Hebrew letters. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 67a) suggests that mastery of this text would allow the mystic to create ex nihilo, out of nothing, and such was done by Rav Oshaya and Rav Chanina every Friday afternoon. These two rabbis would create a chunk of veal, and make a barbecue!

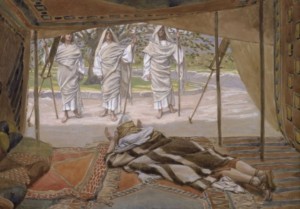

‘Abraham and the Three Angels’ by James Tissot

It appears the same was done by Abraham. We read in Genesis 18:7 that when the angels visited him, Abraham hastened to “make” a calf, v’imaher la’asot oto. The Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush Wisser, 1809-1879) comments on the Torah’s strange choice of verb by stating that Abraham literally created a calf through the wisdom of Sefer Yetzirah. This is why, he explains, the next verse has Abraham serving butter and milk. It is unthinkable that Abraham would serve veal with dairy—an explicit Torah prohibition—unless the veal was of his own creation, and was therefore not real meat that once had a soul. Abraham may have been the first person to serve vegan burgers.

Where did Abraham get this wisdom? According to one tradition, the angel Raziel (literally “God’s secret”) taught these mysteries to Adam. Adam passed it down to his son Seth, and onward it went down to Noah, then to his son Shem. Midrashic texts have Shem teaching Abraham, circumcising Abraham (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 29), and even ordaining Abraham as a priest (Midrash Aggadah, Genesis 14:19).

Alternatively, Abraham received mystical knowledge on his own. Kabbalah implies something “received”, and is often seen as being conferred directly by the Heavens to those who are worthy. In his commentary on Sefer Yetzirah, the Ravad (Rabbi Avraham ben David, c. 1125-1198) lists the names of the angels that taught our patriarchs this mystical wisdom:

The master of Shem was Yofiel. The master of Abraham was Tzadkiel. The master of Isaac was Raphael. The master of Yakov was Peliel. The master of Yosef was Gabriel. The master of Moshe Rabbeinu was Metatron. The master of Elijah was U’maltiel. Each of these angels passed down Kabbalah to his disciple, whether through a book or orally, in order to enlighten him, and to inform him of future events.

According to the Book of Jubilees (12:25), Abraham was also taught Hebrew directly from Heaven. It had been lost following the Great Dispersion of the Tower of Babel. Now, the Holy Tongue was restored. Of course, it wouldn’t have been possible for Abraham to learn Kabbalah and the mysticism of Sefer Yetzirah without knowledge of Hebrew, upon which it is all based. Interestingly, the Book of Jubilees (11:6) also paints Abraham as a great engineer. He first became famous for inventing a seed-scattering device attached directly to a plow, as well as a method for keeping birds from eating the seeds of farmers.

The Torah tells us that at the end of his life, Abraham gave over his entire inheritance to Isaac, his rightful heir, but left various matanot, “gifts”, for his other children (Genesis 25:6). He then sent those other children eastward, to live outside the borders of Israel, so that it would be clear that the Holy Land belongs solely to Isaac and his descendants. What were these gifts? The Sages state that these were kernels of mystical wisdom to take with them. Some say this was white magic, and others black magic. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 91a) associates it with impure wisdom of some sort. Many see in these gifts the mystical wisdom that would give rise to the ancient religions of the Far East. So perhaps there is a connection after all between the Hindu concept of Brahman—and the Hindu priestly caste of Brahmins—with the name Abraham.

While Abraham is generally seen as a forefather—whether biological or spiritual—of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, he is also a forefather of many other nations through his many other children that we often forget about (see Genesis 25). Our Sages say he is called “Avraham” because he is av hamon goyim, the father of a multitude of nations. He might very well be the father of all the world’s major religions, too.