This week’s parasha, Terumah, begins with God’s command for the Israelites to build a Mishkan, an Earthly “dwelling place” for the Divine. God tells Moses (Exodus 25:2-8):

Speak to the children of Israel, and have them take for Me an offering; from every person whose heart inspires him to generosity, you shall take My offering. And this is the offering that you shall take from them: gold, silver, and copper; blue, purple, and crimson wool; linen and goat hair; ram skins dyed red, tachash skins, and acacia wood; oil for lighting, spices for the anointing oil and for the incense; shoham stones and filling stones for the ephod and for the choshen. And they shall make Me a sanctuary and I will dwell in their midst…

God requests that each person donate as much as they wish to construct a Holy Tabernacle. He concludes by stating that when the sanctuary is built, He shall dwell among them. The Sages famously point out that the Torah does not say that God will dwell in it, but in them. The sanctuary was not a literal abode for the Infinite God—that’s impossible. Rather, it is a conduit between the physical and spiritual worlds, and a channel through which holiness and spirituality can imbue our planet.

In mystical texts, we learn that the Mishkan was far more than just a temple. Every piece of the Mishkan—every pillar and curtain, altar and basin, even the littlest vessel used inside of it—held tremendous significance and represented something greater in the cosmos. In fact, the whole Mishkan was a microcosm of Creation. This is the deeper reason for why the prohibitions of Shabbat are derived from the construction of the Mishkan. The passage we cited above appears one more time in the Torah, in almost the exact same wording, ten chapters later. In that passage, we read the same command for each Israelite to donate the above ingredients to build a sanctuary. The only difference is that in the second passage, the construction of the Mishkan is juxtaposed with (Exodus 35:1-2):

Moses called the whole community of the children of Israel to assemble, and he said to them: “These are the things that God commanded to make. Six days work may be done, but on the seventh day you shall have sanctity, a day of complete rest to God; whoever performs work on this day shall be put to death…”

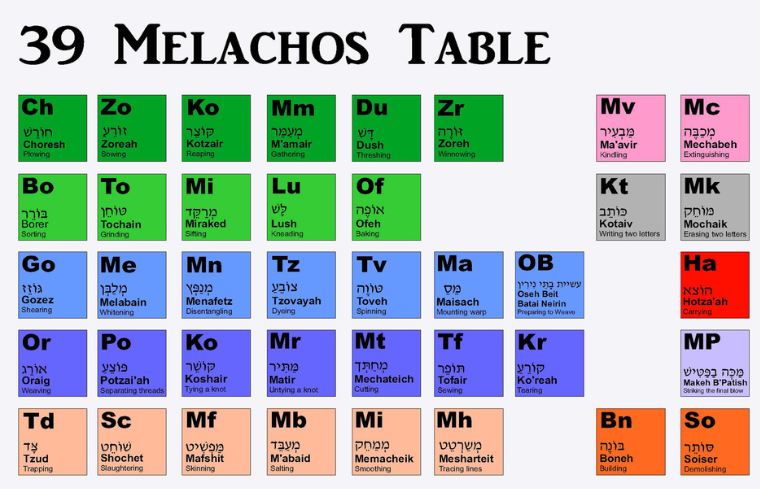

From this clear connection, the Sages learn that the actions required to construct and maintain the Mishkan are the same ones we must abstain from on the Sabbath. There are 39 such melakhot in all. On a more mystical level, these 39 works are said to be those same actions performed by God in creating the universe! For example, the first prohibited work (see Shabbat 7:2) is zorea, “sowing”, or seeding the earth, just as we read in the account of Creation that God said (Genesis 1:11) “Let the earth bring forth grass, herb-yielding seed, and fruit-tree bearing fruit after its kind, in which its seed is found on the earth.” Perhaps the most famous prohibition, mav’ir, “lighting” a flame, parallels God’s most famous Utterance, “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). Such is the case with all 39 prohibited works. In this way, when a Jew rests on the seventh day from such actions, he is mirroring the Divine Who rested from these works on the original Seventh Day.

The Mishkan and the Holidays

The Zohar (II, 135a) comments on this week’s parasha that the ingredients of the Mishkan symbolize the Jewish holidays. The first ingredient is gold, and this corresponds to the first holiday of the year, Rosh Hashanah. The second ingredient, silver, corresponds to Yom Kippur. This is because silver and gold represent the two sefirot of Chessed, “kindness”, and Gevurah, “restraint”. The latter is more commonly known as Din, “judgement”. In mystical texts, silver and gold (both the metals and the colours) always represents Chessed and Gevurah. Rosh Hashanah is judgement day, which is gold, and Yom Kippur is the day of forgiveness, silver.

The third ingredient, copper, corresponds to the next holiday, Sukkot. The Zohar reminds us that on Sukkot, the Torah commands the Israelites to sacrifice a total of seventy bulls, corresponding to the seventy root nations of the world. This is why the prophet Zechariah (14:16) states that in the End of Days, representatives from all nations of the world will come to Jerusalem specifically during Sukkot to worship God together with the Jews.

The Zohar explains that copper is Sukkot because copper (at least in those days) was the main implement of war, which the gentiles use to build their chariots and fight their battles. This, the Zohar explains, is the meaning of another verse in Zechariah (6:1), which states that “…there came four chariots out from between the two mountains; and the mountains were mountains of copper.” The Zohar concludes that the Torah prescribes the sacrifices to be brought in decreasing order (thirteen on the first day, twelve on the second, eleven on the third, etc.) to weaken the drive for war among the gentile nations.

The next ingredient is the special blue dye called techelet, which corresponds to Pesach. As the Talmud (Sotah 17a) states, techelet symbolizes the sea, and the climax of the Exodus was, of course, the Splitting of the Sea. Only at this point, the Torah states, did the Israelites believe wholeheartedly in God, and his servant Moses (Exodus 14:31). The Zohar therefore states that techelet holds the very essence of faith.

Following this is the purple dye called argaman, which is Shavuot. It isn’t quite clear why the Zohar relates these two. It speaks of purple being a fusion of right and left, perhaps referring to the fact that purple (or more accurately, magenta) is a result of a mixing of red and blue. This relates to the dual nature of Shavuot, having received on that day the two parts of the Torah (Written and Oral), and later the Two Tablets, in the month whose astrological sign is the dual Gemini. There is a theme of twos, of rights and lefts coming together. We might add that Shavuot is traditionally seen as a sort of “wedding” between God and the Jewish people, with the Torah being the ketubah, and Mt. Sinai serving as the chuppah.

The sixth ingredient, tola’at shani, red or “crimson” wool, corresponds to the little-known holiday of Tu b’Av. Although the Mishnah (Ta’anit 4:8) states that on Tu b’Av the young single ladies of Israel would go out in white dresses to meet their soulmates, the Zohar suggests that they also wore crimson wool, based on another Scriptural verse (Lamentations 4:5).

Tu b’Av is actually the last holiday that the Zohar mentions. The remaining nine ingredients correspond to the nine days after Rosh Hashanah, through Yom Kippur, ie. the “Days of Repentance”. This brings up a big question: The Zohar relates the ingredients of the Mishkan to the major Torah holidays: Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and the three Pilgrimage festivals (Pesach, Shavuot, Sukkot). Naturally, it omits Chanukah, Purim, the fasts and minor holidays, which are not explicitly spoken of in the Torah. So, why does it mention Tu b’Av? Before we even begin to answer this question, we should already recognize the huge significance of Tu b’Av, strangely one of the most oft-forgotten holidays on the Jewish calendar.

Tu b’Av: a Torah Holiday

The holidays that are not explicitly commanded by God in the Torah were all instituted by future Sages. Purim was instituted by Esther and Mordechai, and first celebrated in Persia. Yet, the Talmud tells us that the majority of the Sages in the times of Esther and Mordechai initially rejected their call to establish Purim as a holiday! (See Yerushalmi, Megillah 6b-7a.) Interestingly, historians and archaeologists have not found a single Megillat Esther among the thousands of Dead Sea Scrolls and fragments, suggesting that the Jews who lived in Qumran did not commemorate Purim. Clearly, it was still a point of contention as late as two thousand years ago.

Chanukah, meanwhile, is not found in the Tanakh at all. Although two Books of Maccabees exist, the Sages did not include them in the final compilation of the Tanakh. Similarly, the later Sages of the Mishnaic and Talmudic era did not find it fit to have a separate tractate for Chanukah, even though there is a separate tractate for every other big holiday.

The fast days are not festivals, but sad memorial days instituted by the Sages to commemorate tragic events. Tu b’Shevat appears to have no Scriptural origins. Yet, Tu b’Av does. The Talmud (Ta’anit 30b) tells us that one of the historical events that we commemorate on Tu b’Av is the fact that the tribe of Benjamin was permitted to “rejoin the congregation of Israel”. In the final chapters of the Book of Judges, we read how a civil war emerged in Israel, pitting all the tribes against Benjamin because of the horrible incident where a woman was brutally raped in Gibeah. The tribe of Benjamin was subsequently cut off from Israel, with their men forbidden from marrying women of other tribes. The ban was eventually lifted on Tu b’Av. The men of Benjamin were told:

“Behold, there is a festival of God from year to year in Shiloh, which is on the north of Bethel, on the east side of the highway that goes up from Bethel to Shechem, and on the south of Lebonah.” And they commanded the children of Benjamin, saying: “Go and lie in wait in the vineyards; and see, and, behold, if the daughters of Shiloh come out to dance in the dances, then come out of the vineyards, and take every man his wife of the daughters of Shiloh, and go to the land of Benjamin…” (Judges 21:19-21)

The Tanakh is clearly describing what the Talmud says would happen on Tu b’Av, when the young ladies would go out to dance in the vineyards to find their soulmates. The exact Scriptural wording is that this day is a chag Adonai, “festival of God”. This is precisely the term used by Moses during the Exodus (Exodus 10:9), possibly referring to Pesach, or more likely to Shavuot (as Rabbeinu Bechaye comments). It is also the term used later in the Torah to describe Sukkot (Leviticus 23:39). Thus, Tu b’Av is evidently a Torah festival, too! And this is why the Zohar singles it out from all the other, “minor” holidays. It seems Tu b’Av is not so minor after all.

The Zohar concludes its passage on Terumah by saying that although we do not have the ability to offer Terumah today, and there is no Mishkan for us to build, we nonetheless have an opportunity to spiritually offer up these ingredients when we celebrate the holidays associated with them. When one wholeheartedly observes Rosh Hashanah, it is as if they offered up gold in the Heavenly Temple, and during Yom Kippur one’s soul brings up silver. Over the days of Sukkot, there is an offering of copper up Above, and on Pesach it is techelet; on Shavuot, argaman, on Tu b’Av, tola’at shani, and on the Days of Repentance the remaining ingredients. On these special days, we help to construct the Heavenly Abode. And this is all the more amazing when we remember that Jewish tradition maintains the Third Temple will not need to physically be built as were the first two, but will descend entirely whole from Heaven.