As we count each day during Sefirat haOmer in the weeks between Pesach and Shavuot, we are conscious of the 24,000 slain students of Rabbi Akiva and observe a period of mourning. It is fitting to think of those victims as we ourselves focus on personal development and self-improvement during this time, in preparation for the Sinai Revelation on Shavuot—which didn’t just take place once some three millennia ago, but happens anew each year. Having said that, it is interesting that we seemingly have so many days of mourning to commemorate the tragedy, yet we don’t have such prolonged mourning for other terrible catastrophes in Jewish history (some of which are arguably much worse). Where did this extended mourning period come from?

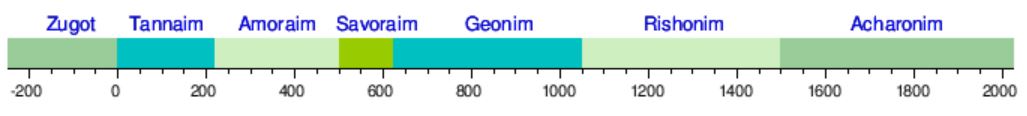

If we look in our legal texts, we surprisingly find very little. The Talmud says nothing about mourning in these days. It is brought down that some of the Geonim (c. 600-1000 CE) may have mentioned mourning during this period, and that there was a custom not to hold weddings between Pesach and Shavuot (see, for instance, the collection of Geonic responsa published in 1802 under the title Sha’arei Teshuvah, #278). It is strange then that the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204), who carefully codified the Talmud and the entire corpus of Jewish law up to that point (including the works of the Geonim!) makes no mention of mourning during the Omer in his monumental Mishneh Torah. The Rambam was Sephardic so one might argue that he may have omitted a custom that developed in Ashkenaz first. Yet, the Machzor Vitry, composed by Rashi’s disciple Rabbi Simchah of Vitry (in northern France) in the 11th century, fails to mention anything about mourning during the Omer either! Neither is it mentioned by great Rishonim like the Rif (Rabbi Isaac Alfasi, 1013-1103) or the Rosh (Rabbeinu Asher, c. 1250-1327).

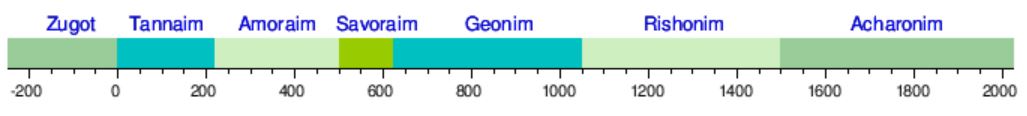

Timeline of Rabbinic history and halakhic eras

Its first notable mention appears to be the Arba’ah Turim of Rabbi Yakov ben Asher (the “Ba’al haTurim”, 1270-1340), son of the Rosh, who was Ashkenazi but lived in Spain. In Orach Chaim 493, he says it is customary not to have weddings during the Omer, though engagements are permitted. He then states that in some places it is also customary not to take haircuts. No mention is made of abstaining from music, avoiding reciting shehecheyanu, or any other mourning rituals. Interestingly, other sources from this time period (like Sefer Asufot) argue that the mourning period arose not because of Rabbi Akiva’s students, but because of the devastation of the Crusades on Ashkenazi communities! Later sources would combine both reasons, and explain that the mourning is both for Rabbi Akiva’s students and for the Crusades.

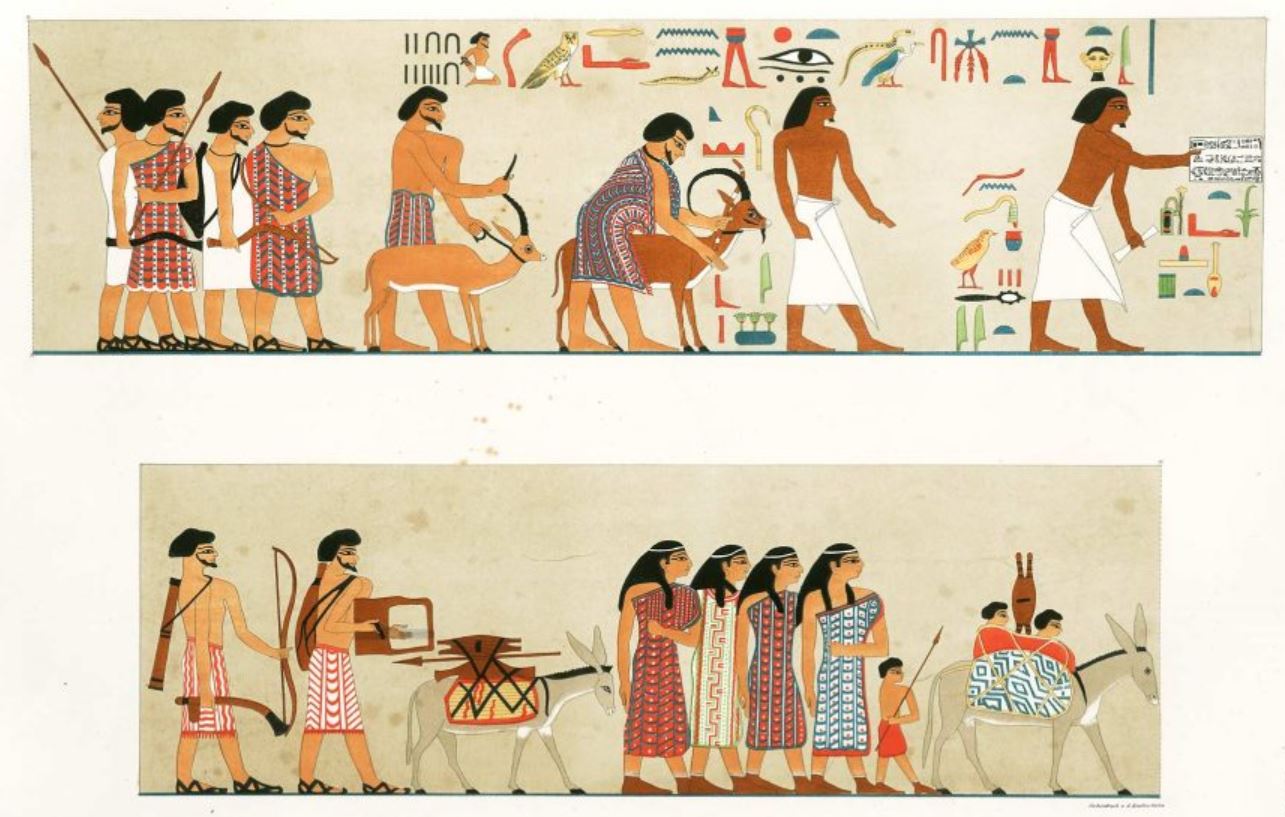

Massacres of Jewish communities around the time of the First Crusade (1096-1102)

It should be noted that there is an alternate, more mystical reason for mourning (or at least, for avoiding festivities) during the Omer: the Mishnah brings an opinion that the wicked in Gehinnom are judged specifically between Pesach and Shavuot (Eduyot 2:10). In truth, this is only a singular opinion of one Sage, contrasting an earlier statement that judgement in Gehinnom lasts a full 12 months. It is possible to reconcile the two opinions by saying that following a person’s passing, their soul is judged for up to 12 months, and then if the verdict is for the person to remain in Gehinnom, they are subsequently rejudged each year between Pesach and Shavuot. Since we know that the deaths of Rabbi Akiva’s students actually ended on Lag b’Omer and did not extend all the way to Shavuot (hence the mourning stops on Lag b’Omer), we might apply that same rule to the judgement in Gehinnom as well. In this case, we have yet another mystical reason for lighting bonfires on Lag b’Omer, as these would be appropriately symbolic of the “flames” of Gehinnom.

The above somewhat contradicts the notion that judgements take place specifically on Rosh Hashanah. We assume that all souls, both Jewish and non-Jewish, living and deceased, are judged on this day. Interestingly, the Arba’ah Turim (in Orach Chaim 581) explains that Jews customarily shave before Rosh Hashanah because, unlike gentiles, we don’t grow out our beards in fear of judgement! We are certain that God will judge us favourably. This notion presents something of a problem for the idea of not shaving because of the judgement in Gehinnom.

Haircuts and Music

Continuing our journey through halakhic history, the next major law code was the Shulchan Arukh (which was really only a summary of the larger Beit Yosef). Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575) produced it by integrating the Mishneh Torah with the Arba’ah Turim, and the Rif, plus updating it with newer established customs, as well as the occasional Kabbalistic practices. It was meant to be a universal code of law, and something like the authoritative “last word”, satisfying the majority of opinions. In our times, Rav Ovadia Yosef famously argued that the Shulchan Arukh should be the supreme code of Jewish law, especially in the land of Israel where it always held primacy since its publication.

Regarding mourning during the Omer, the Shulchan Arukh again mentions only weddings and haircuts. It explains that, of course, the mourning ends on Lag b’Omer, and doesn’t extend all the way to Shavuot. The Rama (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, c. 1530-1572) adds in his gloss for Ashkenazim that some have the custom to allow haircuts until Rosh Chodesh Iyar, and only start the mourning period after this. That actually makes a great deal of sense, since we consider the entire month of Nisan to be a festive month, and we don’t recite tachanun at all throughout the month. This is stated clearly in Masekhet Sofrim 21:2-3, which also says that fasting in Nisan should be avoided (except for the firstborn before Pesach). For this reason, many religious authorities opposed the Zionists establishing Yom HaShoah—Israel’s Holocaust Memorial Day—in Nisan, because there shouldn’t be a mourning day within the festive month. It is therefore quite ironic that, at the same time, many religious authorities typically encourage mourning practices in the same Nisan days for the Omer!

It must be repeated that our ancient Sages did not actually institute such mourning, and it is a later custom. Rabbi David Bar-Hayim argues that the Sages did not institute mourning during the Omer because they understood we already have enough mourning days on the Jewish calendar, particularly on Tisha b’Av and the three weeks leading up to it. If we add several more weeks of mourning during the Omer, plus all the other fast days and sad days on the Jewish calendar, it can become quite depressing and psychologically unhealthy. Rabbi Bar-Hayim adds that while we may have a minhag to mourn during the Omer, it is certified halakhah to honour Shabbat and appear presentable and regal on the holy day, therefore it is entirely permitted to trim or get a haircut before Shabbat, even during the Omer.

For many today, the biggest question during the Omer is regarding listening to music. None of the ancient sources speak of abstaining from music, all the way up to the Shulchan Arukh, and beyond. So where did it come from? In his commentary on the Shulchan Arukh, the Magen Avraham (Rabbi Avraham Gombiner, c. 1635-1682) adds that dancing at parties during the Omer is forbidden. Based on this, Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein (1829–1908) argued in his Arukh haShulchan (first published in 1884) that if dancing is prohibited, then we must extend the prohibition to music as well, since it inevitably leads to dancing. This appears to be the first clear argument anywhere for avoiding music during the Omer. The position has been rejected by others, as there is no direct guaranteed leap from music to dancing. After all, many people listen to music just to relax, or while driving or cleaning, or to motivate themselves to work or exercise, and so on. For these reasons, some only prohibit live music, not recorded music.

Rav Soloveitchik argued that the Omer mourning should have a precedent from other mourning practices, like the shiva, shloshim, or the year-long mourning following the death of a parent. Since the Omer mourning is likened to the latter, the prohibition is only on going to parties or concerts, but not listening to music in private. His contemporaries, Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Ovadia Yosef, disagreed on this and prohibited all music during the Omer. (In the case of Rav Ovadia, this is somewhat inconsistent, since he always argued for the primacy of Shulchan Arukh, which makes no mention of abstaining from music! Nonetheless, it seems he was upholding a modern-day stringency, even if it isn’t mentioned in his go-to law code.)

To summarize, there is no doubt that forbidding weddings between Pesach and Lag b’Omer is based on a valid ancient custom that likely goes back as far as the Geonim. (Though some, even today, do permit and hold weddings up through Rosh Chodesh Iyar.) Abstaining from haircuts is a bit more recent, but still has a source going back some 700 years. It should be remembered that many authorities starting from the Rishonim and up to the present allow haircuts and trimming (or even shaving) to stay presentable, especially in honour of Shabbat, or if necessary for work purposes. This is particularly true if a person is accustomed to trimming or shaving daily.

Finally, regarding music, there is no ancient source for the prohibition. While it is true that one should ideally avoid parties and concerts during the Omer, not listening to music in private is a very recent stringency, perhaps just over a century old. For those who simply cannot go so long without music, there is definitely room to permit it. Either way, there is no need to worry about passively hearing background music in the elevator or supermarket, nor any concern for those who make a living working in the music industry. Nor should a person who has a birthday during the Omer feel condemned to never be able to have a festive birthday party in their life! (See also ‘Should Jews Celebrate Birthdays?’) Lastly, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that, despite the seriousness, the Sefirat haOmer period is simultaneously a time of great joy. The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270)—who also said nothing about mourning during this time—described the whole period from Pesach to Shavuot as chol hamoed, like the intermediate days of a festival (see his comments on Leviticus 23:36). Sefirat haOmer is indeed a festive, positive, and happy time, especially because we have the opportunity to do a most-precious Torah mitzvah of counting the Omer, while eagerly anticipating a new year of Torah learning ahead starting on Shavuot.

Happy counting!

Make your upcoming Shavuot all-night learning meaningful with

Tikkun Leil Shavuot – The Arizal’s Torah Study Guide