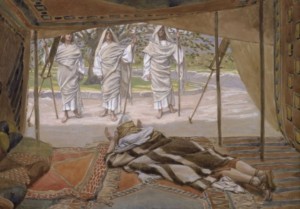

‘Abraham and the Three Angels’ by James Tissot

This week’s parasha, Vayera, begins by telling us that following Abraham’s circumcision, he was “sitting at the entrance of the tent as the day was hot.” (Genesis 18:1) The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1340) offers several interesting possibilities as to why the Torah had to mention this seemingly superfluous detail. One of the answers is that k’chom hayom, the heat of the day, is actually alluding to the heat of Hell. As is characteristic of the Ba’al HaTurim, he proves it mathematically, pointing out that the numerical value of k’chom hayom (כחם היום) is equivalent to “this is in Gehinnom” (זהו בגיהנם), when including the additional kollel.

The Ba’al haTurim also draws on a Talmudic teaching (Eruvin 19a) that Abraham sits at the “entrance” to Gehinnom and pulls out all who are circumcised from there! There is an exception to this, though, for being “circumcised” is more than just the one-time passive active of getting circumcised. A man also has to “uphold” his circumcision, meaning not to abuse that organ. Anyone who was promiscuous over the course of their life has their foreskin grow back in Gehinnom—and those people Abraham does not save!

That said, what exactly is Gehinnom? Is it the equivalent of “Hell”? Does Judaism have a concept of such an eternal place of torment? It is common to hear that Judaism does not have such a notion, and that the Tanakh does not describe such a place. Yet, later Jewish literature is actually quite rich with discussion of a hellish torment of some sort for certain wicked individuals in the afterlife. What is the truth?

Origins of Hell

Aside from brief allusions, the Torah of Moses does not openly speak of any kind of afterlife. The simple reason for this is that God did not want us to focus on the afterlife, the focus should be on the here and now. The Torah is a manual for living properly in this world. Moreover, we shouldn’t be fulfilling God’s commands only because we seek a reward. This is not exactly a pure motive, and the Mishnah reminds us not to be “like those who serve their master for a reward” (Avot 1:3). Similarly, serving God in order to avoid damnation is also not the holiest of motives. Rather, we should fulfill His commands because it is the right thing to do, and because it draws us closer to Him. The Talmud (Sotah 22b) actually speaks of seven types of hypocritical Pharisees, and two of the seven are those that serve God strictly out of fear of punishment, and those who serve only for the love of reward. It is therefore understandable why the Torah generally avoids speaking of the afterlife, save for a small number of brief references.

Most often in Tanakh, we are told of a she’ol, loosely translated as the “underworld”. This term is first introduced by Jacob while grieving for Joseph—whom he presumed dead (Genesis 37:35). Jacob later uses the term again when he feared losing Benjamin, too, saying his soul would suffer immense torment (Genesis 42:38). We then see how Korach and his followers were punished by being sent to Sheol alive (Numbers 16:30-33). Finally, in Ha’azinu, we are told that God’s wrath burns with flames all the way down to the bottom of Sheol (Deuteronomy 32:22). This is probably the earliest direct reference to a burning hell of some sort. Later in Hannah’s Prayer we are told that God “puts to death and brings to life; casts down to Sheol and raises back up” (I Samuel 2:6). From this we learn that hell is not a place of permanent wrath, and those who are sent there may return, for God raises souls “back up”. Job, however, says that some go there and never come back (7:9).

Next, it was David’s turn to pray (II Samuel 22), and in his song which he sang when God saved him from “the hand of Saul” he said how “The snares of Sheol encircled me, the traps of death engulfed me.” This was a beautiful and poetic play-on-words from David, since Sheol is spelled identically to Shaul (שאול), “Saul”, from whom he had been saved. Here we see the clearest connection so far between death and Sheol. When David’s greatest royal descendent, King Hezekiah, prayed after his own recovery he said how he feared being “consigned to the gates of Sheol for the rest of my years, and I thought I shall never again see God…” (Isaiah 38:10) Here we learn that those who are sent to Sheol are cast away from God.

David’s son, Solomon, said that those who “forsake discipline” and “spurn reproof will die, Sheol and Avadon are opposite God—how much more so the hearts of men!” (Proverbs 15:11) Here we are introduced to a new realm far from God: Avadon. The Zohar (III, 54b) explains that Avadon is the deepest pit of Hell, from which none can escape. It literally means a place of “total abandonment”. In fact, Jewish texts speak of seven levels to Gehinnom (Sotah 10b), and the Zohar explains that Sheol is just one of the seven levels (as explored in the past here). The levels of Gehinnom are called, in order: “Pit”, “Grave”, “Silence”, “Filthy Mud”, “Sheol”, “Shadow of Death”, and “Underworld” (בּוֹר. שָׁחַת. דּוּמָה. טִיט הַיָּוֵן. שְׁאוֹל. צַלְמָוֶת. אֶרֶץ תַּחְתִּית). Where did the overarching term Gehinnom come from?

Origins of Gehinnom

Valley of Hinnom in 1948

The Valley of Ben-Hinnom, Gei ben Hinnom in Hebrew, or just Valley of Hinnom, is a lowly place outside the Old City of Jerusalem (which is up on a hill). Since Jerusalem is a holy place and priests walked its streets regularly, it was forbidden to bury the dead within its walls. Instead, the dead were buried in the valleys below, outside the city. Numerous such ancient burial chambers have been found in the Valley of Hinnom by archaeologists. Thus, from the earliest days we see an association between Hinnom and the dead.

Soon, the Valley of Hinnom served as a sort-of garbage dump for the holy city, too, and a place where impure things were taken out to be burned (see Radak on Psalms 27:13). It was also the place where the city’s rejected would flee, and where the wicked idolaters gathered. God would later tell the prophet Jeremiah to go to the Valley of Hinnom and warn the sinners there that they would be utterly destroyed: “A time is coming—declares God—when this place shall no longer be called Topheth or Valley of Ben-Hinnom, but Valley of Slaughter.” Another reason this valley was associated with fire is because it was said that people sacrificed their children to various false deities there, by passing them “through the flames”. Isaiah called this place a “firepit” (30:33), and in his concluding verse he describes how those wicked people who rebelled against God and were slaughtered, “their worms shall not die, nor their fires quenched…” (66:24) This final verse implies an eternal “burning” of the wicked.

One of the fundamental principles in Judaism (especially in Jewish mysticism) is that this physical world is a reflection of the spiritual world. So, just as there is a Jerusalem down here, there is a Yerushalayim shel Ma’alah, a “Heavenly Jerusalem” above. Just as there was a Garden of Eden down here for the righteous to delight in, there is a Garden of Eden above for the souls of the righteous. Similarly, just as there was a Gehinnom down here for the sinners and idolaters, there is a spiritual one for the wicked to receive their punishment. In fact, the spiritual worlds pre-existed the physical, and Gehinnom was already forged on the Second Day of Creation (see, for instance, Yalkut Shimoni I, 5).

This punishment in Gehinnom is not spiteful or vengeful, but a fitting retribution for the sins of the wicked. It is not about imposing pain and cruelty, but about rectifying and purifying their contaminated souls. As such, the Mishnah states that the punishment of the wicked in Gehinnom lasts a maximum of 12 months (Eduyot 2:10). The Zohar (I, 62b, 68b) comments on this that the Great Flood lasted 12 months for the same reason, as God had decreed a “Hell on Earth”. And, just as the Great Flood involved boiling water from below and freezing rain and hail from above, so too is the judgement in Gehinnom divided up into six months of fire and six months of ice. However, it appears that this is only for the worst of sinners. An alternate opinion in the same Mishnah above says the punishment really just lasts from Pesach to Shavuot, ie. the 49 days of Sefirat HaOmer. This provides us with a deeper reason as to why this time is traditionally a period of “mourning”, introspection, and personal development. The Bartenura comments on the Mishnah that the cleansing period doesn’t take place specifically in those weeks only, since people obviously die throughout the year, but rather that the punishment lasts a maximum of seven Sabbaths, or 49 days.

The Sages agree that Shabbat extends to the netherworld as well, and the wicked souls enjoy a break on the Sabbath. The Ba’al haTurim (on Exodus 32:3) notes that one of the deeper reasons as to why we are forbidden from lighting a fire on Shabbat is to mirror God, who does not ignite the flames of Hell on Shabbat either. He further points out that when the Torah says that God rested on the Seventh Day, vayinafash (וינפש), it hints to the fact that the souls in Gehinnom rest, too: the numerical value of vayinafash is the same as “for those who are in Gehinnom” (אלה שבגיהנם)! The Zohar adds that the sinners in Gehinnom have a break on Rosh Chodesh as well (Zohar I, 62b). Here the Zohar also notes that the angel who holds the keys to Gehinnom is named Samriel. Interestingly, the Zohar teaches that when Israel recites amen, yehe shemeh rabbah during Kaddish, God’s mercy is aroused and He has compassion over the souls in Gehinnom. Thus, three times a day when Israel is reciting the prayer services—and the Kaddishes within them—the souls in Gehinnom get some relief! The Talmud (Shabbat 119b) similarly states that one who recites that line with full kavanah has the gates of Eden opened for him, among other benefits.

Having said all of the above, the Arizal taught that the majority of sinners don’t actually go to Gehinnom.

Hell on Earth

The Talmud (Chagigah 27a) tells us that Torah scholars are spared from the flames of Gehinnom. Studying God’s Word creates a spiritual protective barrier around one’s soul, preventing the Torah student from descending to Hell. The Arizal takes it a step further and says that most people are entirely spared from Gehinnom the first time around. Instead, they are sent back to Earth into a new body to try again. A person is typically given three such chances to improve upon their past life. If, after three reincarnations, the person has not been able to fulfill their mission and has only become worse, then they are sent to Gehinnom, since clearly reincarnation is not working out for them. If a person does improve with each reincarnation, then they can keep coming back even up to a thousand times. (See Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 4 and 22.)

All of this is secretly encoded in the Torah verses describing God’s 13 Attributes of Mercy, where we read that He “extends kindness to thousands, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; yet He does not remit all punishment, but visits the iniquity of parents upon children and children’s children, upon the third and fourth generations.” (Exodus 34:7) Since the Torah also tells us that each person dies only for their own sins (Deuteronomy 24:16), it doesn’t make sense that the sins of parents are passed on to their children. Instead, it means that a person’s sins pass on from one life to their next life, “to the third and fourth generations”, meaning up to a maximum of three reincarnations. This is further supported by Job 33:29-30, where we read that “Truly, God does all these things, two or three times to a man, to bring him back from the Pit, that he may bask in the light of life.” In other words, God spares a person from Gehinnom for two or three reincarnations, to let them live again and have another chance.

The Arizal further taught, based on the Zohar, that when the Tanakh spoke of kaf hakelah, the cosmic “slingshot”, it was secretly referring to reincarnation. This term comes from I Samuel 25:29, when the prophetess Abigail blessed her future husband David: “And if anyone sets out to pursue you and seek your life, the life of my lord will be bound up in the bounds of life with Hashem, your God; but He will fling away the lives of your enemies as from the hollow of a sling.” Some saw within this “sling” a type of punishment in Hell where one’s soul is “flung” back and forth across the universe. The Arizal said this “flinging” is simply referring to reincarnation, where the soul is “flung” from one body to another. (See Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 22; Zohar II, 99b. For more on the mechanics of reincarnation, see here.)

The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) seemingly had a totally different understanding. In his commentary to the tenth chapter of the Mishnah’s Sanhedrin, he gives a long exposition about the afterlife. He starts by outlining five different perspectives and beliefs among Jews: The first group believes in an eternal Eden for the righteous and an eternal Gehinnom for the wicked. The second group believes all reward will be in the Messianic Age, when humans will merit to live forever, while the wicked simply won’t be there to enjoy it. The third group similarly believes that the righteous will resurrect in the End of Days and enjoy a perfect world, while the wicked will not merit this. The fourth group believes life will continue more or less as it is now, except that Jews will no longer be subjugated and will be back in their land with a rightful kingdom. The fifth group combines all of the above, saying that after Mashiach comes, there will be a Resurrection of the Dead for the righteous to return, and then they will enjoy a renewed Garden of Eden on Earth forever.

The Rambam goes on to outline his vision, arguing that anything physical cannot be eternal or perfectly good. The perfect good is spiritual only, so the ultimate afterlife is an eternity basking in spiritual pleasure, beyond this world. He argued that righteous souls with refined intellects will merit this reward, while wicked souls and unrefined minds will simply be “cut off” and not exist any more. This view is somewhat at odds with the earlier Sages, who argued that the final Judgement Day will take place when body and soul reunite at the End of Days, then give their just reward or punishment. This was at the heart of a debate between Rabbi Yehuda haNasi and the Roman emperor Antoninus (as explored in the past here).

The Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, 1194-1270) went with that view, suggesting in his Discourse on Rosh Hashanah that those who pass away are in a temporary “sleep” mode until the Resurrection of the Dead at the End of Days. Then soul and body come back together, all are judged, and received their reward or punishment. How do we make sense of all of these diverging views? Thankfully, there is a way to reasonably synthesize all of these different perspectives, satisfying all opinions from the Mishnah and Talmud to the Rambam and Ramban, the Zohar and the Arizal. We can put it together as follows into one complete view on what happens to a person when their physical body dies:

Souls that need rectification are reincarnated. It is important to remember that souls are not bound by time like the body, and can be sent into a new form at any point across time and space. After three failures, they are directed to the future Judgement at the End of Days. Souls of the righteous that need no rectification and have no reason to return are immediately sent ahead to the Resurrection at the End of Days. Gan Eden and Gehinnom are actually right here on Earth—as they always were, and as described in Tanakh. The suffering for the wicked lasts twelve months as the Mishnah in Eduyot states, with body and soul together as maintained by Rabbi Yehuda haNasi. And here we might suggest something especially significant in light of what is happening in the world around us now.

The Mishnah states that the final apocalyptic war of Gog u’Magog lasts twelve months just like the judgement in Gehinnom. Perhaps they are really one and the same. The tribulations of Gog u’Magog are the suffering and final purification of souls before the advent of the idyllic Messianic Age. Like the Zohar’s description of the “Hell on Earth” Flood, the war of Gog u’Magog may serve as a “Hell on Earth” where all of the fire, brimstone, hail, and torment is experienced. In fact, the Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 44:21) suggests this very notion, saying that the exile, subjugation, and persecution of Israel is equivalent to the torment of Gehinnom, and God gave us the former in place of the latter!

Finally, all of this might explain the alternate opinion in the Mishnah that the duration of suffering will not last twelve months, but just from Pesach to Shavuot. We know that Pesach is the time of Redemption, so perhaps it will be the start of that last phase of “Hell on Earth” purification. The necessary judgements, wars, and travails can take place within the span of 49 days. Those that have a chance to be rectified will be rectified, while the hopeless wicked souls will be obliterated for good. After this we will wake up to an era of peace and prosperity; to a newly restored world, a Garden of Eden for the righteous.

May we see that day soon.

Pingback: Reincarnation in Judaism, Part 2 | Mayim Achronim