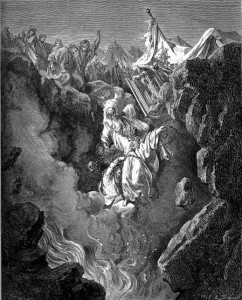

This week’s parasha, Korach, describes the rebellion instigated by Moses’ Levite cousin Korach. Korach’s main accusation was against Aaron and the Kohanim: why did they tale all the priestly services for themselves and left nothing for the lay Israelite? Had not God stated that all of Israel will be a holy nation of kohanim? (Exodus 19:6) Why did only a small group of people (Aaron and his descendants) suddenly become kohanim? His argument was actually a valid one, and Rashi (on Numbers 16:6) records that Moses even agreed with Korach to some extent, and said that he too wishes that all of Israel could be priests! Why weren’t they?

The classic explanation is because of the sin of the Golden Calf. Before this, there was no need for a special contingent of kohanim. Instead, the firstborn male of each family would automatically go into the priesthood. Many hold that there was no need for sacrificial offerings at all had it not been for the Golden Calf. After that grave sin, a rectification was needed in the form of sacrifices and related services. And, because only members of the tribe of Levi did not participate in the Golden Calf incident, they merited to become the priests that facilitate those rectifications.

Since Moses was up on Sinai, Aaron was in charge at the time, and he selflessly tried to take the sin of the Calf upon himself. Thus, it was Aaron specifically that was given the priesthood. Henceforth, every firstborn male would have to be redeemed from priestly service, as we read again in this week’s parasha (Numbers 17:15-16). This pidyon haben ceremony is still done today for a firstborn male child (under the right conditions), with five silver coins given to a kohen in order to redeem (or exempt) the boy from priestly service.

The big question is: if Korach was really correct about all of Israel being priests, why was so he severely punished? Did he really forget about the Golden Calf, and why it was that only Aaronides could be kohanim? Not likely. One possible answer can be found in last week’s parasha, where we read of the Sin of the Spies. There, God condemned Israel to remain in the Wilderness for forty years, and for that entire adult generation to perish. Before this, as many Torah commentators agree, what was meant to happen is that the Israelites would effortlessly reconquer and settle their Holy Land, build the Temple, and usher in the Messianic age, with Moses as Mashiach. Following the Sin of the Spies, that potential reality collapsed. This led directly to Korach’s rebellion in this week’s parasha.

Previously, when it was made clear that only Aaron and his sons would be kohanim because of the Golden Calf, Korach must have reasoned (correctly) that this is a temporary arrangement. Once the Messianic age begins, all sins are rectified, and everything would revert to its original state. Israel would once more be a “kingdom of priests” as God intended. However, because of the Spies God decreed for Israel to remain in the Wilderness, and for that whole adult generation (including Korach) to die. Korach realized the Messianic age would not be coming so soon, and he would never get to be a kohen—hence the rebellion.

For Korach, the nail on the coffin was, as the Midrash states (Bamidbar Rabbah 18:2), that he sought his own personal aggrandizement. He saw how Moses was the leader, and his brother Aaron was the high priest, and a younger cousin Elitzafan was appointed head of the Levites. Where was Korach’s honour? This was his fatal flaw. His rebellion was not really about elevating all of Israel to the status of priests. That was just a nice argument to rouse the masses. It was really about his own status and power. For this he failed, and for this he was punished.

How did he not see his own downfall? The Midrash (ibid. 18:8) adds that Korach foresaw that the great Samuel (Shmuel) would be one of his descendants. This was proof to him that he could not fail. And the Tanakh (Psalm 99:6) implies that Samuel was as great as Moses and Aaron combined. As the progenitor of Samuel, Korach therefore believed he had the power to overthrow both Moses and Aaron. The Midrash states that Korach miscalculated. Some of his sons did not end up participating in his rebellion, and repented wholeheartedly before the Earth swallowed up Korach and the rest of his family and supporters. These sons of Korach survived, and we even have multiple Psalms recorded in their name (such as Psalms 42 and 44). The Midrash concludes that from one of these great sons descended Samuel. And from I Chronicles 6:7 we learn that this son was named Asir (אסיר).

The Kabbalists take it one step further and reveal a far more intriguing link between Korach and Samuel, which actually goes all the way back to the first family.

Sparks of Cain and Abel

In multiple places, the Arizal (Rabbi Itzchak Luria, 1534-1572) explains the spiritual dynamics of the first sons, Cain and Abel. In Sha’ar HaPesukim on this week’s parasha (as well as on parashat Balak, and in Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 32, 36, and 39) he states how the souls of Cain and Abel were composed of smaller sparks. Abel’s contained 37 sparks, alluded to by the gematria of his name, הבל being 37. Cain’s soul contained 308 sparks, many of which he damaged with the sinful murder of his brother. These 308 sparks returned in Korach to be rectified. This, too, is alluded by the gematria of his name, קרח being 308. It was Moses who was able to rectify all of these sparks—the 37 of Abel and the 308 of Korach—and this is why the gematria of Moses’ name is 345 (משה), the sum of 37 and 308!

We have already briefly discussed how Moses rectified some of these sparks in the past (see here and here, for instance). What we have not mentioned yet is the connection to Samuel. The Arizal taught that of the 308 sparks of Cain, a portion of the pure ones that were not tarnished (particularly those associated with the soul level of Ruach) returned in Samuel. So, Korach contained all 308 sparks of Cain, including those good ones. As we’ve seen, Korach wasn’t all bad, and he had valid arguments. Those good parts of him reincarnated in Samuel. In other words, Samuel was a rectified Korach! He was Korach without the impure sparks and without the poor character traits. In fact, a closer look in the Tanakh reveals some incredible parallels between the two.

Korach sought to dethrone Moses and Aaron. He wanted to be the leader of Israel, like Moses, as well as the high priest, like Aaron. He wanted to be elevated from the rank of Levite to the rank of kohen. He hoped to be a part of the Messianic age. And all of this is precisely what happened with Samuel:

The Tanakh describes Samuel as the last judge of Israel (I Samuel 7:6). Recall that the judges were the leaders of the nation following Moses. In some ways, Moses can be considered the first “judge”. Samuel was the last. The Tanakh states Samuel was a Levite (I Chronicles 6:7-13), yet describes him as fulfilling priestly functions. In I Samuel 7:9 he is making a sacrifice like a kohen. More surprisingly, in I Samuel 2:18 he is wearing an ephod, a special garment typically reserved only for the kohen gadol. Some believe he was filling in for Hofni and Pinchas, the wicked sons of Eli the High Priest. Whatever the case, Samuel clearly takes on the role of a kohen, despite being a Levite.

We can now see why Samuel is described as being equivalent to both Moses and Aaron, for he alone acted as both supreme leader of Israel and the top priest of his generation. In this way, Samuel fulfilled all the desires of Korach: ascending from a Levite to a kohen, becoming the leader of the nation, and even serving as a high priest. And what of his desire for the Messianic era? Of course, it was Samuel who anointed King David, thereby establishing the Davidic dynasty, and the lineage of Mashiach.

In Samuel, those good sparks within Korach finally got everything they wanted.