‘Eliezer and Rebekah’ by Gustav Doré

In this week’s parasha, Lech Lecha, we are introduced to Abraham’s loyal servant, Eliezer (Genesis 15:2). Eliezer was a righteous man and wanted nothing more than to be a full-fledged part of Israel. He hoped to marry into Abraham’s family, too, but because he was a Canaanite, and the Canaanites were deemed cursed, it was not possible. Nonetheless, the Arizal (Sha’ar haPesukim on Chayei Sarah) explains that in his future life, Eliezer reincarnated in none other than Caleb, the righteous spy and leader from the Tribe of Judah. In fact, the Arizal explains that this is why Caleb went to visit the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron at the start of his spy mission (Sotah 34b). He specifically wanted to pray at the grave of his former master, Abraham, and hoped that just as Abraham had helped him in his past life, he would assist him again in the difficult journey he was on.

Interestingly, the minor Talmudic tractate Derekh Eretz Zuta actually states that Eliezer was one of nine immortal people who never died. These special people merited to enter the Garden of Eden alive and well. As a quick aside, Derekh Eretz Zuta is a fascinating tractate that reads like Pirkei Avot, with maxims from the Sages on ethics, morals, and life advice. It begins with the following statement:

The ways of a scholar are that he is meek, humble, alert, fulfilled, modest, and beloved by all. He is humble to the members of his household, sin-fearing, and judges people according to their deeds. He says “I have no desire for all the things of this world because this world is not for me.” He sits and studies, dusting his cloak at the feet of the scholars. In him no one sees any evil. He questions according to the subject-matter and answers to the point.

The last three verses in the first chapter tell us about some of the greatest figures in Jewish history. First the tractate points out (with citations to prove it) that God forged a covenant with seven people in Tanakh: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Pinchas, and David. One might notice that these are nearly the same as the Seven Shepherds made popular by the Sukkot ushpizin, with the exception being Pinchas in place of Joseph. The truth is that Pinchas and Joseph are spiritually linked, with Pinchas containing a spark of Joseph. Kol HaTor (Ch. 2) even states that Pinchas was the potential “Mashiach ben Yosef” of his generation. There is mathematical proof to this, too, with “Pinchas” (פינחס) being 208, exactly like “Ben Yosef” (בן יוסף).

We are then told that seven people were so righteous and holy that their bodies never decomposed: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Miriam, and Amram. Some also add David to this list. Finally, the chapter ends with nine people who merited to enter the heavenly Garden of Eden alive: Enoch, Eliyahu, Mashiach, Eliezer, King Hiram, Eved-Melekh the Cushite, Yaavetz “the son of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi”, Batya the daughter of Pharaoh, and Serach bat Asher. Some add a tenth person to the list: Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi. What was so great about these individuals?

Becoming Immortal

Enoch (Hanokh) was a seventh-generation descendant from Adam. Recall that in Adam’s genealogical list, Enoch is the only one that is not described as having died (Genesis 5:18-24). Instead, the Torah says that he went to “walk with God” and that God “took him”. According to the mystical tradition, he did not die and was transfigured into the angel referred to as “Metatron”. (For the whole story of Metatron, and his real angelic name, see the class here.)

A number of reasons are given for why Enoch merited immortality. First and foremost, he avoided the sins of the pre-Flood generations and remained a faithful servant of Hashem. In fact, according to the ancient Book of Jubilees (4:27-32), it was he that testified against the sinners on Earth (both humans and “fallen angels”) before the Heavenly Court. Jubilees also tells us that Enoch was the first scribe, teacher, and astronomer. It was he that taught humans the first calendar (4:21-22). The ancient mystical text known as the Book of Enoch (which is referenced countless times throughout the Zohar) is attributed to him. According to Midrash Talpiot (Letter Chet), Enoch was originally a shoemaker, and with every stitch he would meditate upon God and recite the verse Barukh shem kevod malkhuto l’olam va’ed.

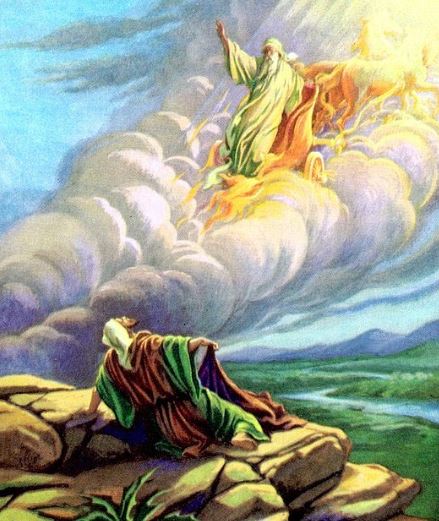

‘Elijah Taken Up to Heaven’

Similar to Enoch, the Tanakh clearly describes how Eliyahu never died and was taken alive to Heaven in “a fiery chariot with fiery horses” (II Kings 2:11). Eliyahu jumps into the Tanakh narrative quite suddenly, with no genealogy and no background story. This is because, according to tradition, Eliyahu was actually the same person as Pinchas, whom God had given an eternal “covenant of peace”. (For lots more on this, see ‘Pinchas is Eliyahu—and So Much More’.) Eliyahu, too, was “zealous for God”, and was one of the last remaining true prophets in a time of rampant idolatry. His miraculous performance on Mt. Carmel inspired the masses to return to Hashem (though unfortunately not for too long). For being so zealous in upholding God’s brit, he became the angel of brit, and bears witness at every brit milah ceremony.

Then we have Eliezer, Abraham’s trusted servant since his early days in Ur-Kasdim. According to Sefer haYashar, Eliezer was originally a servant of King Nimrod, and joined Abraham after seeing his miraculous escape from the fiery furnace. (Targum Yonatan 14:14 goes further and says Eliezer was also the son of Nimrod!) Eliezer is most famous for selflessly and faithfully arranging Isaac’s engagement to Rebecca. He was also a fierce warrior who fought bravely alongside Abraham. When we read in this week’s parasha that Abraham took 318 men with him to go to war against the four wicked kings, the Talmud (Nedarim 32a) clarifies that 318 men refers to just Eliezer (אליעזר), whose numerical value is 318! (As explored in the recent concluding class on the Noahide Laws, the number 318 is actually deeply significant in Kabbalah, and is associated with righteous gentiles like Eliezer.)

Next on the list is the Phoenician king Hiram of Tyre. Recall that he was the one that provided most of the materials and artisans for the construction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. He was a great friend of both Kings David and Solomon. For being so generous and helpful in building God’s House, he merited immortality. That said, a parallel passage in Yalkut Shimoni (II, 367) states that Hiram should not be on the list, and it should be Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi instead. His story is recounted in the Talmud (Ketubot 77b), leading off from a discussion about the terrible disease called ra’atan:

Rabbi Yochanan would announce: Be careful of the flies found on those afflicted with ra’atan [as they are carriers of the disease]. Rabbi Zeira would not sit in a spot where the wind blew from the direction of someone with ra’atan. Rabbi Elazar would not enter the tent of one with ra’atan, and Rabbi Ami and Rabbi Asi would not eat eggs from an alley in which someone with ra’atan lived. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, however, would attach himself to them and study Torah with them, saying: “The Torah is a loving hind and a graceful doe.” (Proverbs 5:19) If it bestows grace on those who learn it, does it not protect them from illness?

When Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi was on the verge of dying, they said to the Angel of Death: “Go and perform his bidding”. The Angel of Death went and appeared to him. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said to him: “Show me my place [in the afterlife].” He said to him: “Very well.” Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said to him: “Give me your sword, lest you frighten me on the way.” So he gave it to him.

When they arrived [at the gates of Eden], he lifted Rabbi Yehoshua [so he could see], and showed it to him. Rabbi Yehoshua jumped over to the other side. The Angel of Death grabbed him by the corner of his cloak. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said to him: “I swear that I will not come with you.” The Holy One, blessed be He, said: “If he ever in his life requested dissolution of an oath he had taken, he must return [as he can have his oath dissolved this time also]. If he did not ever request dissolution of an oath, he need not return.” [Since Rabbi Yehoshua had never requested dissolution of an oath, he was allowed to stay in Heaven.]

The Angel of Death said to him: “At least give me my knife back.” He did not give it to him [as he did not want any more people to die]. A Divine Voice emerged and said to him: “Give it to him, as death is necessary.” Eliyahu the Prophet announced before him: “Make way for the son of Levi! Make way for the son of Levi!”

Rabbi Yehoshua was a very pious and righteous man, so much so that he even taught Torah to people who were dangerously infectious. He merited to greet the Angel of Death and request how he would die. Rabbi Yehoshua asked to hold onto Death’s sword while Death showed him his portion in the afterlife. But he then tricked Death and jumped into Eden alive. He vowed never to leave, and since he had never broken or dissolved a vow while he was alive, he was permitted to stay in the afterlife, having never actually died or given up his body. (For those who might be wondering how it is possible to enter Heaven directly with a body, see here.)

Next on the list is a little-known Biblical figure named Eved-Melekh the Cushite. He is mentioned in one place, Jeremiah 38. When the prophet Jeremiah was predicting the destruction of Jerusalem, his critics had him arrested and thrown into a pit. He was nearing death when a eunuch named Eved-Melekh (literally “servant of the king”) besought King Zedekiah to spare the prophet. Zedekiah agreed, and Eved-Melekh took 30 men with him to save Jeremiah. For this selfless act, Eved-Melekh merited eternal life. We don’t know much else about this mysterious figure.

There are two women on the immortals list. First is Serach, the daughter of Asher. She was the one that broke the news to Jacob that Joseph was still alive. Jacob was so happy and thankful, he blessed Serach and she ended up living for centuries. We know this because she is mentioned both in Genesis 46, when Jacob’s family first descends to Egypt, and again in Numbers 26, when the Israelites who had come out of Egypt are numbered in the Wilderness! (The full story of Serach was explored in the recent class on Lebanon & Iran here. See also ‘The Incredible Story of Serach bat Asher’ in Volume One of Garments of Light.) The other woman on the list is Batya (or Bitiya), the daughter of Pharaoh, who found baby Moses and brought him up in her home. According to the Zohar (III, 167b), both women currently have Heavenly academies where they teach Torah.

That leaves us with two more mysterious figures on the list. One is referred to as “Yaavetz the son of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi”. This is absolutely puzzling, because nowhere do we see any discussion of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi having a son named Yaavetz! Nor are we told anything about why he merited such a great honour of entering Eden alive. In all of my research, I could not find anything about such a person. However, there is a person named Yaavetz mentioned in Tanakh. His story is told in I Chronicles 4, which begins “The sons of Judah: Perez, Hezron, Carmi, Hur, and Shobal.” The chapter records the descendants of the original Yehuda, son of Jacob. We are then told that “Yaavetz was more esteemed than his brothers; and his mother named him Yaavetz because she said, ‘I bore him in pain [otzev].’” Yaavetz was apparently a very famous individual, one of the greatest members of the Tribe of Yehuda, more esteemed than his kinsmen. Various commentaries on this verse say he did a great deal to spread Torah and mitzvot.

The following verse says “Yaavetz called on the God of Israel, saying: ‘Oh, bless me, enlarge my territory, stand by me, and make me not suffer pain from misfortune!’ And God granted what he asked.” (v. 10) It isn’t clear what exactly was causing Yaavetz so much pain, but the Tanakh says God granted his request to never suffer again. Presumably, that means he didn’t experience death either! With this in mind, I believe that the Talmudic statement on the immortality of “Yaavetz the son of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi” is a mistaken reading; it should be “Yaavetz the descendant of Yehuda”, the forefather of the Tribe and its first nasi. There is some extra proof for this because in the same chapter (I Chronicles 4:18) we find another immortal—Batya the daughter of Pharaoh!

The last puzzle on the list is Mashiach, strange because Mashiach has still not come. Does his inclusion in the list mean that when Mashiach does come, he will never die? This is at odds with other statements (such as Rambam on Sanhedrin 10:1) that suggest Mashiach will indeed die, and his son and grandson will rule after him (which makes perfect sense, since he needs to re-establish the Davidic dynasty). Isaiah 11:10 states that his resting place will be an honoured pilgrimage site. I think one reason why Mashiach may have been included in this list of immortals is to counter Christianity. The entire Christian religion is built upon the idea that the Messiah died to redeem the world. Christianity does not work without the death of the Messiah. (Its very symbol is the cross upon which he died.) So, maybe this is why the Talmud affirms the real Mashiach will never die at all! That said, in another place the Talmud has a similar list of immortals, but without any mention of Mashiach.

More Immortals

We find a parallel “immortals” passage in another minor Talmudic tractate called Kallah Rabbati. Over there (3:25), it’s not nine people that are listed, but seven: Serach, Batya, Hiram, Eved-Melekh, Eliezer, the grandson of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi, Yaavetz, and some say Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi. Interestingly, the grandson of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi is considered a different person from Yaavetz! The Yaavetz here is indeed the one in I Chronicles 4. The Talmud gives a good reason for the immortality of all the figures, but none for the grandson of Rabbi Yehuda. This only further proves that it should just read Yaavetz, the descendant of Yehuda, and not Yaavetz the son (or grandson) of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi.

Missing from the Kallah Rabbati list are Enoch, Eliyahu, and Mashiach. We can certainly understand why. Enoch and Eliyahu were different from the others because they didn’t just avoid death and enter Eden alive, but actually transfigured into angels. And, as discussed above, Mashiach shouldn’t really be in this list at all, since he should die like all human beings. Alternatively, one might argue that he will not die because he will usher in the era of Resurrection, when there will be no more death anyway. Perhaps Mashiach was mentioned in the first list only because he is expected to make a trip through Heaven at some point, much like Enoch was taken up to “walk with God” on a tour of the upper worlds. (The details of Mashiach’s trip to Heaven were discussed in the third part of the series on Mashiach ben Yosef here.)

To complete the analysis, we must mention two more sources. In addition to naming the nine immortals from Derekh Eretz Zuta, the same Yalkut Shimoni cited above adds that a total of thirteen people “never tasted death”. The additional four are the righteous Methuselah, son of Enoch, the longest-living person mentioned in Tanakh (though the Torah explicitly says that he did die, clocking in at 969 years), and the three sons of Korach. Recall that the Torah tells us all of Korach’s family perished, “but the sons of Korach did not die.” (Numbers 26:11) His three sons Asir, Elkanah, and Aviasaf survived, and went on to compose a number of Psalms that we still recite today. The Midrash explains that just as they were falling into the flaming pit with the rest of the family, they sang wholeheartedly to Hashem and were spared death. It seems they never died at all afterwards.

The phrasing of the above Midrash begs the question: Is there a difference between “entering the Garden of Eden alive”, and “not tasting death”? Our final source (Resheet Chokhmah, Chuppat Eliyahu Rabbah, 3:18) doesn’t think so, and says that “Nine people entered the Garden of Eden alive and did not taste death: Benjamin son of Jacob, Kileav son of David, Serach bat Asher, Batya bat Pharaoh, Eliezer the servant of Abraham, Eved-Melekh the Cushite, Eliyahu, Yaavetz son of Rabbi Yehuda, and some also say Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi.” The two new names here are Benjamin and Kileav. The latter is mentioned only in passing in Tanakh (in II Samuel 3:3, and seems to be called “Daniel” in I Chronicles 3:1). Nonetheless, the Talmud (Shabbat 55b) says he was entirely sinless. The Talmud here actually says Benjamin and Kileav did die, but only “because of the Serpent”, ie. due to Adam and Eve bringing death into the world in Eden, not because they themselves deserved to die. The same is true for Amram, father of Moses, and Yishai, father of David.

To summarize, the indisputable list of immortals is: Eliezer, Eved-Melekh, Batya, Serach, and Yaavetz, plus Enoch and Eliyahu who transformed into angels. The ones that were likely immortal, but subject to some dispute, are Hiram, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, and the three sons of Korach. And the ones that are probably not immortal, but are so righteous and special that they could be, are Methusaleh, Benjamin, Kileav, Amram, Yishai, and Mashiach.

Shabbat Shalom!