This week we begin reading the third book of the Torah, Vayikra, called “Leviticus” in English because it mainly focuses on priestly laws and Temple services—facilitated by the tribe of Levi. We know that only a specific clan within the tribe of Levi, the descendants of Aaron, were the kohanim directly responsible for the offerings and rituals. The rest of the tribe of Levi had other tasks, including overseeing the refugee cities across the Holy Land, educational roles, supporting the kohanim, and serving as singers and musicians in the Temple. That last role was so significant that our Sages state a sacrifice that was brought without musical accompaniment was not valid!

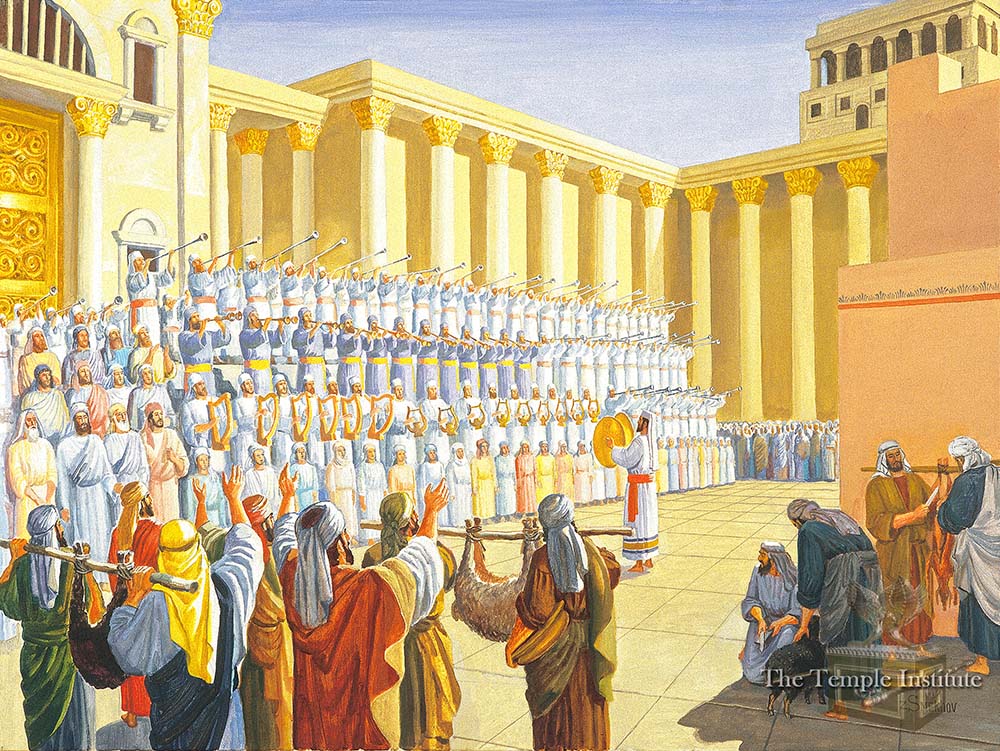

“The Levitical Choir” in the Temple, with harps, lyres, trumpets, flutes, and cymbals. (Credit: Temple Institute)

The Sages devote several pages to these matters in the little-known tractate Arakhin. The Mishnah (2:3) begins by describing the use of trumpets, lyres, and flutes in the Temple. It concludes by providing several opinions as to who were the main musicians, whether they were slaves, Israelites from the family of Pegarim and Tzippara or, of course, the Levites. The Talmud (10a) then goes into a discussion about which special days require recitation of Hallel, and suggests that in ancient times Hallel was musically accompanied by a flute, halil. The proof is Isaiah 30:29, which states: “For you shall be singing as on a night when a festival is hallowed; there shall be rejoicing as when they march with flutes, to come to the Mountain of God, to the Rock of Israel.” This teaches both that we must sing to God on a holiday (“when a festival is hallowed”)—as we indeed do through Hallel—and that it should be accompanied by flutes!

We are then told that we don’t say Hallel on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur because these are more solemn days of judgement. The angels protested to God that the Jews aren’t singing, and He replied: “the King is sitting on the throne of judgment and the books of life and the books of death are open before Him, yet the Jewish people should sing joyous songs of praise before Me?” (Arakhin 10b) We also learn here that we don’t need to recite Hallel on Purim because the Megillah itself is a form of Hallel, and qualifies as a song praising God.

The Talmud then tells us about other instruments used in the Temple, including a copper cymbal and a magreifa. The latter was composed of ten pipes, and was something like a mini-organ. The Talmud notes that an actual organ was not found in the Temple. The Talmudic term is a hyrdolim, the Greek hydraulis, or hydraulic organ. It could very well be that the magreifa is the same instrument as the ‘asor mentioned by King David (Psalm 92). ‘Asor means “ten” and it is thought to be a ten-stringed instrument, but it might actually be the ten-piped magreifa.

We are then presented with a discussion regarding whether the primary component of music were the vocals or the instruments? (There are arguments in favour of both positions, with no clear conclusion.) Finally, we learn that without music, the sacrifices were invalid (11a). Rabbi Meir uses a Torah verse (Numbers 8:19) to prove that “just as the atonement is an indispensable component of the offering, so too the song of the Levites is indispensable.” Rav Yehuda adds: what does it mean when the Torah commands to “serve with the name of God”? (Deuteronomy 18:7) It means to serve God through song!

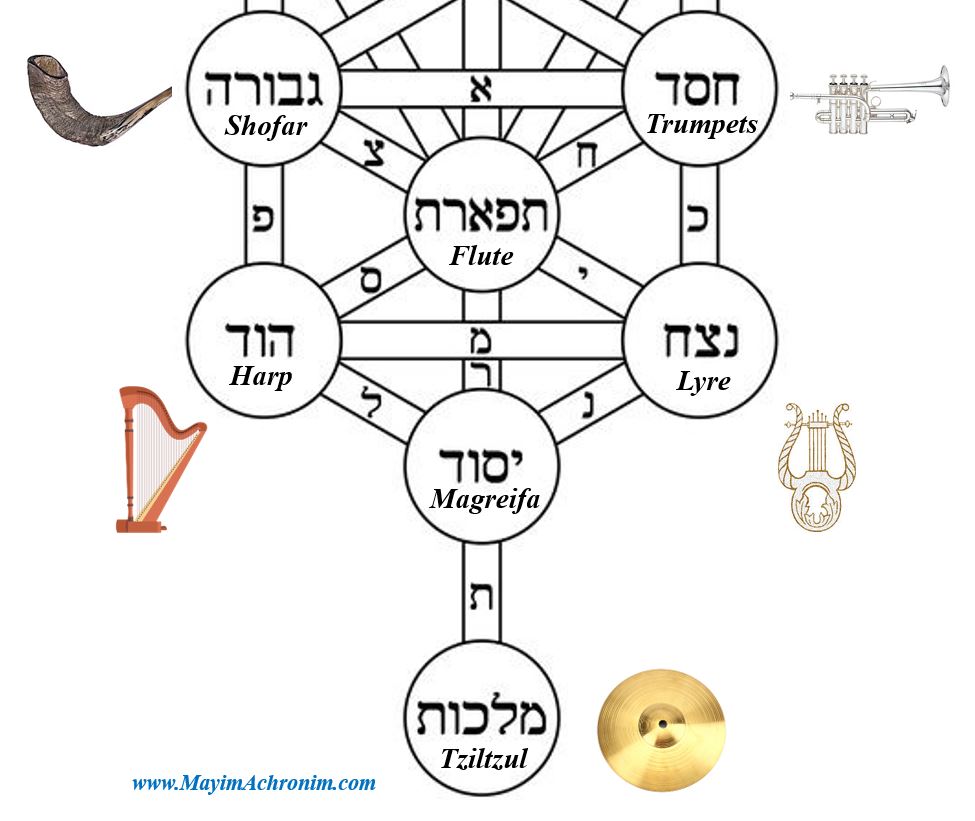

Altogether, we find a total of seven instruments used in the Temple: the trumpets (hatzotzrot) and the shofar, the lyre (navel), the flute (halil), and the magreifa, plus the harp (kinor) and the cymbal (tziltzul). The latter is the only percussion instrument, and parallels the timbrel (tof) mentioned in Psalm 81:3 as one of the instruments used on the holidays. These neatly parallel the seven lower Sefirot (which themselves parallel the seven musical notes):

The trumpets were made of silver (as God commands in Numbers 10:2), and silver is always indicative of Chessed. Meanwhile, the shofar blast is meant to blow away the “left side” of the Sitra Achra and subdue Satan, corresponding to Gevurah on the left. The central halil which accompanied most of the services and the Hallel lines up with the central Tiferet. The twin instruments harp and lyre (which is really just a portable mini-harp) are the twin Sefirot of Netzach and Hod. That leaves the piped magreifa for Yesod and, finally: The tziltzul (cymbal) parallels the percussive tof introduced in the Torah as the choice instrument of Miriam when she led the ladies in song at the Splitting of the Sea (Exodus 15:20). It corresponds to the feminine Malkhut.

The seven instruments played in Jerusalem’s Holy Temple, and how they correspond to the seven lower Sefirot.

There is a further allusion to this special set of instruments in the final 150th psalm of King David:

Halleluyah, praise God in His sanctuary; praise Him in His heavenly stronghold. Praise Him for His mighty acts; praise Him for His exceeding greatness. Praise Him with blasts of the horn [shofar]; praise Him with lyre [navel] and harp [kinor]. Praise Him with timbrel [tof] and dance; praise Him with minim and ugav [corresponding to magreifa and halil]. Praise Him with resounding cymbals [tziltzul]; praise Him with loud blasts [teruah of the trumpets]. Let all that breathes praise God, Halleluyah!

Now, the Mishnah above specifically states that these instruments accompanied the offerings on a yom tov, and in Psalm 92 (Mizmor Shir l’Yom haShabbat), King David says it is good to praise God on Shabbat with the harp, lyre, and other instruments. If that’s the case, why is playing musical instruments halakhically forbidden on Shabbat and yom tov today?

Musical Instruments on Shabbat

The Mishnah states that the Sages enacted certain fences to preserve the sanctity of Shabbat. These extra restrictions are referred to as shevut, and the Mishnah (Beitzah 5:2) lists them as follows: “One may not climb a tree, nor ride on an animal, nor swim in the water, nor clap his hands together, nor clap his hand on the thigh, nor dance.” The Talmud (Beitzah 30a) then comments that regarding clapping and dancing, “nowadays, we see women do so, and yet we do not say anything to them.” So, it seems the Sages were not especially strict regarding the musical prohibitions. Later, the Talmud explains why the Sages forbid clapping and dancing: “so that one wouldn’t repair a musical instrument.” (36b) Some read this to say “so that one wouldn’t create a musical instrument”, which makes a lot more sense, since we know building something new is forbidden on Shabbat.

Elsewhere, the Mishnah adds to the discussion in stating: “One may tie [on Shabbat] a string that came loose from a harp in the Temple, but not in the rest of the country. And tying the string to the harp for the first time is prohibited both here and there.” (Eruvin 10:13) So, in the Temple (where music was played on Shabbat), fixing strings on a harp was permitted. Outside the Temple, however, such fixing was not permitted. And tying up the strings for the first time—ie. creating the instrument—is forbidden everywhere on Shabbat. Either way, the typical musician neither creates nor fixes his own instruments (as this requires a specialist). Thus, later sources read the prohibition as not just one of repairing or creating an instrument, but even just tuning an instrument. On the following page (Eruvin 104a), the Talmud seems to prohibit all instrumental production of sound on Shabbat. The reason appears to be the same: lest one come to fix a musical instrument.

The Rambam (Hilkhot Shabbat, Ch. 23) and Shulchan Arukh (Orach Chaim 399) both go on to ban clapping on Shabbat because it might lead a person to tune an instrument. However, the Rama (Rabbi Moshe Isserles, c. 1530-1572) comments that we are no longer stringent regarding clapping, mirroring the statement of our Sages in Beitzah about the clapping and dancing women. He adds that the typical musician wouldn’t fix his own instrument anyway, so there is further room for leniency. He also permits whistling on Shabbat, and even Sephardic poskim are lenient when it comes to whistling using one’s mouth.

To summarize, we went from being allowed and encouraged to play instruments on Shabbat in the Tanakh, to limiting musical instruments on Shabbat to the Temple, and then to prohibiting musical instruments on Shabbat entirely. And then some went even further to prohibit clapping, tapping, flicking, and dancing. All apparently because we might inadvertently “fix” an instrument. Objectively speaking, the rationale is pretty weak. And it begs the classic question:

How much power and authority do rabbinic extras and stringencies really have? Does something d’rabbanan have the power to override a clear d’oraita? (For more on this perplexing question, see ‘Do Jews Really Follow the Torah?’ in Garments of Light, Volume One.) After all, King David said it is good to praise God on Shabbat with a harp and a lyre (Psalm 92). Isaiah said we should do the same on holidays with flutes (30:29). The Torah clearly commands that we should blow our trumpets on holidays: “And on your joyous occasions, your festivals and new moons—you shall sound the trumpets over your offerings and your sacrifices. They shall be a reminder of you before your God: I, Hashem, am your God.” (Numbers 10:10) And since the Sages instituted prayers instead of offerings nowadays, one can further argue that we really should accompany our prayers with musical instruments!

The Mishnah cited above says the halil accompanied Hallel, and the Talmud adds that the offerings were no good if they didn’t have musical accompaniment. So why don’t we accompany our own offerings with music? Why not recite Hallel to the sound of a halil like they used to? If music was played in the Temple on Shabbat, it implies there is nothing inherently wrong with playing music on Shabbat. It is not genuine hillul Shabbat, though it would be hillul shevut, transgressing an extra rabbinic prohibition. Yet, even that prohibition was in order to prevent someone from fixing an instrument, and this isn’t applicable in the vast majority of cases. Indeed, we find that Jews in times past, at least as late as the era of Rishonim, did play musical instruments on Shabbat. In fact, the Meiri (Rabbi Menachem “Don Vidal Solomon” Meiri 1249-1315) criticizes the students of the Ramban (Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman “Nachmanides”, 1194-1270) for playing musical instruments on Shabbat! (Magen Avot, 10)

Now, one could argue that playing musical instruments is a creative exercise, and Shabbat is about restricting creative labours. On a more mystical level, God created the world through sound, speaking the cosmos into existence. There is scientific evidence to support this, as quantum physicists who hold by String Theory posit that the entire universe—and all of its fundamental forces—can be reduced to a set of vibrating “strings”. Everything comes down to vibrations. So, we don’t play our string instruments on Shabbat, and avoid making new vibrations altogether. While intriguing, this argument is faulty because we are still allowed (and encouraged) to sing and speak on Shabbat, so we are making creative vibrations anyway!

Another explanation, offered by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, is that on Shabbat we avoid instrumental music because we want to empower the human voice. We use our own God-given bodily “instruments” to produce sound. This is somewhat related to the approach of Rabbeinu Chananel (c. 980-1055), who ties the prohibition of music on Shabbat to avoiding excessive sound or noise on Shabbat (Shabbat 18a). Music can be highly positive and spiritual, but it can also be cacophonous and harsh. On Shabbat, we want to give our ears a rest. This is a particularly solid argument for today’s day and age, when music is readily available round-the-clock and people are exposed to music constantly, every day. It’s certainly a good idea to give our ears a rest from music at least one day a week!

Maybe this is the real reason why our Sages prohibited musical instruments on Shabbat, despite the fact it was once permitted. Another reason might be related to the wider statement that once the Temple was destroyed, all music was forbidden, even singing! (Gittin 7a) Of course, such a universal ban on music was never accepted. Yet, the prohibition of music on Shabbat was accepted—perhaps because music on Shabbat was particularly associated with the Temple services.*

That initial universal ban on music may seem extreme and bizarre: how could the Sages ban music when it is so important and spiritually significant? Perhaps our Sages did not envision the Temple would be in ruins for so long. After all, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 97a) brings an opinion that the time of Mashiach would begin in the year 4000 (or 240 CE). When they made such a ban, they probably though it was temporary, and the Temple would soon be rebuilt and music restored. Yet here we are, nearly two millennia later. There is a light at the end of this long tunnel, though, and it seems we are finally close to the Redemption now; to the rebuilding of the Temple, along with the return of all forms of uplifting music, inside the Temple and outside the Temple, on weekdays and even on Shabbat.

Shabbat Shalom and Chag Purim Sameach!

For more on music in Judaism, see:

‘Kabbalah of Music and the Piano’

‘Listening to Non-Jewish Music’

‘Kabbalah of Music’ (Video)

*Interestingly, Conservative Judaism began to permit music in the synagogue on Shabbat in the 1950s, arguing that since we consider the synagogue a “mini-Temple”, the principle of ain shevut b’mikdash should apply to the synagogue as well! For an extensive halakhic analysis of music on Shabbat from two Conservative scholars, see here.