This week’s parasha, Toldot, begins with a focus on Isaac, now forty years old and finally married. Commenting on this, the Zohar says some incredible things. Embedded here in the Zohar is a deeply mystical text known as Midrash HaNe’elam, “the Hidden Midrash”. It is both an integral part of the Zohar (with others sections of it peppered throughout the Zohar’s many volumes) and a distinct work with its own flavour. It, too, dates back to the 2nd century CE teachings of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. Midrash HaNe’elam explains that Isaac was “brought back to life”, so to speak, by his wife Rebecca. How so?

We find that after the Akedah, Isaac seemingly disappears from the narrative. The Torah tells us that Abraham returned to Be’er Sheva, but nothing is said of Isaac. There are various opinions as to what happened to Isaac during this time. Whatever the case, he reappears only when Rebecca is brought to marry him, at the end of last week’s parasha. As such, the Zohar says that Rebecca was responsible for “resurrecting” Isaac. With this as an analogy, Midrash HaNe’elam segues into a discussion of the Resurrection of the Dead and the End of Days.

There is a lot more to this than meets the eye, since our Sages teach that Isaac, Yitzchak (יצחק), is an anagram of ketz chai (קץ חי), literally “lives at the end”, or “lives [again] at the End of Days”. One of the meanings of this is that Isaac’s life is a model for understanding the End of Days. And so, Midrash HaNe’elam goes on to outline the events of the End of Days, based partly on the life of Isaac and Rebecca. In the same way that Isaac was “resurrected” in his fortieth year, the Resurrection of the Dead for all righteous souls is said to take place forty years into the Messianic Era. Before this, at the start of the Messianic Era, Jews will return to Israel from around the world, ending the long exile, and the Jerusalem Temple will be rebuilt.

Midrash HaNe’elam makes an interesting prediction regarding the timing of these events. There are certain years of history that are particularly auspicious to usher in the End of Days. The Zohar sees a hidden allusion to one such auspicious year in Leviticus 25:13: “In this Jubilee year, each of you shall return to your plots.” The Zohar asks: why does the Torah say this Jubilee year? It should have just said that on each Jubilee, once in 50 years, every Jew returns to his ancestral plot of land in Israel. The answer is that the Torah is secretly referring to the final Jubilee, when all Jews will finally be free. The Zohar then suggests that the word hazot (הזאת), “this”, hints to the year in which it will happen. If read in the standard notation of Hebrew chronology, ה׳זא״ת, it would give an exact year: the ה referring to our current millennium, and the זא״ת adding up to 408. This works out to the year 5408 AM, or 1647-1648 CE. (Our current year is ה׳תשפ״ב, 5782 AM).

Thus, the Zohar states that one particularly auspicious time for the Redemption to begin is in the year 1648. Indeed, Jews at that time waited fervently for the arrival of Mashiach. This was greatly exacerbated by the fact that the years prior to 1648 marked the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, the deadliest conflict in the continent’s history (relatively, it was even worse than World Wars I and II). At the same time, in 1648 raged Khmelnitsky’s uprising that saw countless Jews slaughtered in a series of pogroms across Eastern Europe. Many Jews unsurprisingly believed it must have been the devastating End Times war as described in detail in the Tanakh by prophets like Ezekiel and Zechariah.

One Jew at the time took advantage of the messianic fervour and the difficult state of the Jewish people. In 1648, a mystic from Smyrna named Shabbatai Tzvi (1626-1676) declared himself the long-awaited messiah. Sadly, multitudes of Jews became convinced that he must be the one. When word got to the Ottoman sultan, he had Tzvi arrested and forced him to convert to Islam or die. Tzvi chose to convert to spare his life. At this point, the vast majority of the Jewish world recognized him as yet another imposter. However, a small group of Jews continued to believe in the supposed messiahship of Shabbatai Tzvi, giving rise to a “Shabbatean” cult that persisted for some time afterwards. When Tzvi died, with no Redemption in sight, even fewer followers remained. 1648 was long passed, and it seemed nothing had changed.

Was, then, Midrash haNe’elam wrong? At first glance, it appears so. However, when we unravel the convoluted strings of history, we find that this Midrash haNe’elam prophecy may indeed have ushered in, perhaps with a hint of irony, the modern era.

1648: Birth of the Modern Era

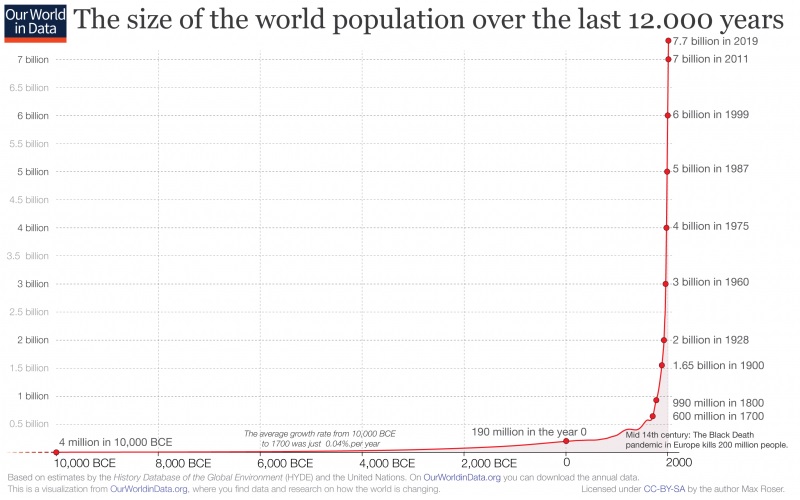

Historians look back at 1648 as a hugely significant year. With the end of the catastrophic Thirty Years’ War, things started to change dramatically. Some mark this time as the start of the “Age of Reason”, and a new era of humanism. Interestingly, it has been pointed out that since 1648, Earth’s population has been on a continuous, near-exponential rise.

A number of critical things happened in 1648 that changed the planet forever. The end of the Thirty Years’ War reshaped the Western world and was the driving force behind the future unification of various central European states into a new and powerful Germany. Across the channel in England, the deeply-religious Puritans took over the government, had King Charles I executed and, in that same January of 1649, received a request to allow Jews to resettle in England. Jews had been expelled from England back in 1290 and were forbidden from living on the island. After some important work by Rabbi Menashe ben Israel, Jews were finally permitted to come back.

Famous portrait of Rabbi Menashe ben Israel by Rembrandt. Rembrandt was a close friend of the Jewish community, and produced multiple prized works depicting the Jews of Amsterdam.

Meanwhile, the Shabbatean movement that launched in 1648 had its own lasting impacts on the course of Judaism. In the 1700s, rabbis around the world fought tirelessly to destroy any shreds of Shabbateanism that might have remained. Possibly the most vocal was Rabbi Yakov Emden (the Ya’avetz, 1697-1776), son of the famed Chakham Tzvi. Another was Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov (1698-1760), founder of Hasidism. In fact, the main reason why the Baal Shem Tov decided to launch the Hasidic movement publicly is to counter Shabbateanism, to provide a kosher alternative for those seeking mysticism and redemption, as well as to “reignite” Judaism after the depressing disappointment of Shabbatai Tzvi.

One of the most renowned experts on the history of Shabbateanism (as well as Hasidism) was Gershom Scholem. He argued, based on earlier sources, that one of the reasons the Baal Shem Tov died so young is because of his grief over the new quasi-Shabbatean cult of the Frankists (see Scholem’s Kabbalah, pg. 300). Thankfully, Frankism didn’t last long at all, and Shabbateanism essentially disappeared altogether. However, Scholem argued that many former Frankists and Shabbateans found a comfortable home in the new movement of “Reform Judaism” (pgs. 304-308). In fact, the first Reform temple in Prague was founded by a group of Frankists! Other former sectarians were led towards the Haskalah, the so-called Jewish “Enlightenment”.

Why did former Shabbateans flock to Reform and Haskalah? The main reason is because the Shabbateans had argued, as did the Christians long before them, that since the messiah had come there was no longer any need to keep the laws of the Torah (or most of them anyway). Like Christianity before it, Shabbateanism became an antinomian (ie. anti-law) movement. It was secular at its core (though still claiming to be “mystical” and “spiritual”). It is therefore no wonder that former Shabbateans rushed to Reform and Haskalah, both of which were secular, anti-Torah outlets.

Now let’s piece all of the above together:

That special year prophesied in the Zohar—1648—saw the origins of Germany, and the start of the Jewish return to England. It saw the birth of Shabbateanism, which led (whether directly or indirectly) to the rise of Reform, Haskalah, and, lehavdil, Hasidism. With Hasidism, the deepest wisdom of the Torah began to be openly revealed around the world. With Chabad Hasidism in particular, the modern baal teshuvah movement took off, and myriads of Jews exiled around the world began to return to the Torah, in fulfilment of Biblical prophecy. Meanwhile, fueled by secular Jews (thanks to the influence of Reform and Haskalah), the Zionist movement which had originally begun as a strictly religious movement, took off as well. While the First Aliyah (1881-1903) was almost entirely made up of Hasidic Jews from Russia and Eastern Europe, the Second Aliyah (1904-1914) was mostly made up of idealistic secular Zionists.

A few years later, the Balfour Declaration (the anniversary of which is this week) made a renewed Jewish state possible. Arthur Balfour was the English foreign secretary who was close friends with a number of influential English Jews. It was the British wresting the Holy Land from the Ottomans during World War I (with the help of their Jewish Legion) that allowed Israel to be formed on a political level. And the final impetus for this was, of course, the Holocaust, perpetrated by Germany.

We can therefore see how 1648 was an absolutely pivotal year both in world history, and in Jewish history. The return of the Jews to England allowed them to eventually become wealthy and influential there, leading to Balfour’s sympathy and declaration. The seeds of Germany’s unification in 1648 would ultimately lead to World War I, allowing the British to capture the Holy Land from Germany’s Ottoman ally. It would later result in the Holocaust which, as terribly tragic as it was, did result in more global support for a Jewish state. And as horrible as Shabbateanism proved to be, there was something of a silver lining in that it sparked several new and diverse Jewish movements, ultimately leading to renewed interest in returning to Israel, and renewed interest in returning to the Torah.

One might be tempted to point to all kinds of popular modern-day conspiracy theories here, but there is no need to resort to conspiracy at all. The truth is, we know that God is in charge of everything that happens, and Himself carefully weaves the tapestry of history. Nothing happens unless it is meant to and, one way or another, all goes according to His plan. This does not absolve those who commit evil, for even when such wicked people veer the world off course, God finds a delicate way to, eventually, bring it back on track. This is one of the great joys of learning history, and it is a privilege to live at a time when so much historical information is freely available, for it allows us to see God’s fingerprints through it all.