Rabbi Shlomo Goren blows the shofar by the Western Wall during the 1967 liberation of Jerusalem.

This Thursday evening, the 18th of Iyar, we mark the mystical holiday of Lag b’Omer. Ten days later, on the 28th of Iyar, we commemorate Yom Yerushalayim, when Jerusalem was liberated and reunified in 1967 during the miraculous Six-Day War. At first glance, these two events may seem completely unrelated. However, upon deeper examination, there is actually a profound and fascinating connection between the two. To get to the bottom of it, we must first clarify what actually happened on these dates in history to uncover their true spiritual significance.

Did Rashbi Die on Lag b’Omer?

It is commonly believed that Lag b’Omer is the yahrzeit, or hillula, of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, better known as Rashbi. Recall that Rashbi was one of the five remaining disciples of the great Rabbi Akiva. He would go on to spend some 13 years in a cave with his son, penetrating the depths of Torah and learning with the angel-prophet Eliyahu. The mystical teachings he later revealed were recorded by his disciples and transmitted in secret for centuries, until collected into the Zohar and first published in the 13th century.

The Zohar completely transformed Judaism, impacting every aspect from prayer and ritual to law and custom. It is said that the mystical circle of Rabbi Moshe de Leon decided to publish the Zohar in the 13th century primarily in order to save Sephardic Jewry. At the time, Jews in Spain were assimilating in huge numbers. Rabbi Moshe de Leon sought to inject new life into Judaism, to show the deeper meaning behind the laws and narratives of the Torah. The Zohar revolutionized the Jewish worldview from one that was about serving God to one that was about serving God through rectifying the cosmos. In the mystical conception, every Jew has tremendous importance and a unique mission to repair the universe. No longer reserved only for the few initiates, the publication and revelation of the Zohar gave every Jew an opportunity to be a mystic. And it worked! Sephardic Judaism was reinvigorated and stayed strong for centuries, to the present day, having never succumbed to any significant secularist or reformist movements.

A few hundred years later, the Ashkenazi world started to face similar issues as the Sephardis had. When secularism swept Europe’s Jews in the 18th and 19th centuries, the first Hasidim understood what needed to be done. They looked at the Sephardic playbook and introduced (or re-introduced) the Zohar to the public. With mysticism infused into daily life, the Hasidic movement exploded and spread rapidly across Europe. (The Hasidic Ashkenazi siddur is still referred to as Nusach Sefarad, to the confusion of many!) The Zohar played such an important role that one of the early Hasidic leaders, Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz (1726-1791), emphatically stated that “the Zohar has kept me Jewish”.

And so, the teachings of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai saved Judaism, twice. Therefore, there is much to celebrate on Lag b’Omer, a day commemorating the revelation of these teachings. While it is generally said that Rashbi died on Lag b’Omer, and that was the day that he revealed the teachings, this is not quite accurate. First of all, Rashbi taught his disciples for many years, and at least one of his students, Rabbi Abba, had been recording the discourses all along (see Scholem’s Kabbalah, pg. 219, citing Rabbi Moshe Galante’s commentaries). We know what it was, specifically, that Rashbi revealed on his deathbed, for this is a distinct text called the Idra Zuta, and it makes up only a very tiny part of the Zohar.

Rabbi Chaim Hezekiah Medini (1834-1904) was born in Jerusalem and went on to serve as the chief rabbi of Crimea for 33 years. He eventually returned to Israel and served as chief rabbi of Hebron. He was revered by both Jews and Muslims as a holy man. Rabbi Medini presided over some of the first modern settlements in Israel, and described this as “holy work”, and the key for realizing the Final Redemption.

Now, there is essentially no evidence to suggest that the Idra Zuta happened on the 18th of Iyar, which is always the 33rd day (ל״ג) of the Omer (hence Lag b’Omer). Nowhere in the writings of the Arizal, for instance, is there a mention of Lag b’Omer being connected to the death of Rashbi. In Sdeh Chemed, Rabbi Chaim Hezekiah Medini (1834-1904) noted that Lag b’Omer is the day Rabbi Akiva started teaching his five last disciples—Rashbi being one of them—and when Rashbi also received his semikhah.

The Talmud (Yevamot 62b) tells us that Rabbi Akiva lost 24,000 students between Pesach and Shavuot, and the Roman “plague” that consumed them ended on Lag b’Omer. Rabbi Akiva found five new students that day and started teaching them. However, Rabbi Akiva was executed before he could complete their training, and did not ordain them himself (with the exception, possibly, of Rabbi Meir). The Talmud records elsewhere (Sanhedrin 14a) how they were ordained:

The wicked kingdom [of Rome] decreed against Israel that anyone who ordains will be killed, and anyone who is ordained will be killed, and the city in which they ordain will be destroyed, and the signs identifying the boundaries of the city in which they ordain will be uprooted.

What did Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava do? He went and sat between two large mountains, between two large cities, and between two Shabbat boundaries—between Usha and Shefaram—and there he ordained five elders. And they were: Rabbi Meir, and Rabbi Yehuda, and Rabbi Shimon [bar Yochai], and Rabbi Yose, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua.

When their enemies discovered them, Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava said [to the newly-ordained]: “My sons, run for your lives.” They said to him: “Our teacher, what will be with you?” He said to them: “I will plant myself like a stone that cannot be overturned…” The [Roman soldiers] did not move from there until they had pierced him three hundred times with iron spears…

To save Judaism from extinction, Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava found a secret place where he managed to complete the ordination of Rabbi Akiva’s five students, including Rashbi. Rabbi Yehuda sacrificed himself to save their lives. It appears that they got their semikhah on the same day they had begun learning with Rabbi Akiva years earlier, on Lag b’Omer. Those five students went on to revive Judaism. So, this revival is what we commemorate on Lag b’Omer. If that’s the case, how did Lag b’Omer became associated with Rashbi’s passing?

Pilgrimage to Meron

Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620), in his extensive recordings of the Arizal’s teachings, only mentions Lag b’Omer once. In Sha’ar HaKavanot, he says that there was a custom to visit the graves of Rashbi and his son Rabbi Elazar on Mt. Meron during Lag b’Omer (see Inyan HaPesach, Derush 12). Rabbi Vital notes that the Arizal did once make such a pilgrimage with his family, too. However, Rabbi Vital also notes that the Arizal did not shave or cut his hair at all between Pesach and Shavuot. The custom of cutting hair at Meron did not originate with the Arizal. So, where did it come from?

Long before the Meron pilgrimage, there was a custom to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem on the 28th of Iyar. This is the yahrzeit of Shmuel HaNavi, the Biblical prophet Samuel. Samuel plays one of the most instrumental roles in the Tanakh, and he is so important that our Sages equated him with Moses and Aaron combined, based on Psalms 99:6: “Moses and Aaron among His priests; and Samuel, among those who call on His name—when they call to God, He answers them.” We see that Scripture places Moses and Aaron on one hand, and Samuel alone on the other, among those greats who get an instant answer when they call on God. The 28th of Iyar was once observed as a fast day commemorating the yahrzeit of Samuel (as codified in the Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chaim 580:1-2). On that day, many would make a pilgrimage to the prophet’s tomb, about 4 kilometres northwest of the Old City, atop a hill that provides excellent views of Jerusalem. (That hill is now the neighbourhood of Givat Ze’ev, a “settlement” named after Ze’ev Jabotinsky, and built atop the ancient Biblical town of Givon, “Gibeon”. We will come back to this.)

The important detail here is that Samuel was a nazir. From birth, he was dedicated to divine service, and “no razor ever touched his head” (I Samuel 1:11). Therefore, a custom emerged to take children to the tomb of Samuel, on the prophet’s yahrzeit, for the children’s very first haircut. (For more on this, see ‘The Mysterious Custom of Upsherin’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.) However, the Mamluks who were ruling over Jerusalem in the 15th century had imposed harsh restrictions on the Jews of Jerusalem and barred Jewish pilgrims, too. It wasn’t until the Ottomans took over in 1516 that things started to open up for the Jews. So, pilgrims attempting to reach Samuel’s Tomb were blocked and redirected. They went instead to the tombs on Mt. Meron. By the time Rabbi Vital was writing at the end of the 16th century, the custom of cutting hair at Samuel’s Tomb in Jerusalem shifted to cutting hair at Rashbi’s Tomb on Meron. It seems that soon enough the yahrzeit of Samuel was confused with the yahrzeit of Rashbi. This is why Lag b’Omer became associated with Rashbi’s passing.

In reality, as we have seen, Lag b’Omer was the day Rashbi became a student of Rabbi Akiva, and when he later received semikhah from Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava. It is also most likely the day when Rashbi first began revealing the secrets of the Zohar. Why would he choose this day for the revelation? There are several big reasons:

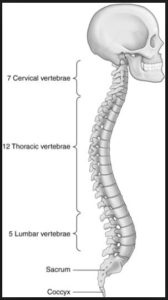

First, the number 33 plays an important role in mysticism. It represents the process of spiritual ascent. This is mirrored biologically in the fact that a newborn child has 33 bones on the vertebrae. There are 33 rungs from the bottom tip of the torso—a place of waste and excretion—up to the brain, the seat of the neshamah. As a person grows, the 33 bones fuse into 26, the value of God’s Ineffable Name. This is meant to signify, among other things, that one’s growth through life should be about attaining understanding of, and unity with, God. The purpose of the 33 is to reveal the wisdom of the 26. King David, who reigned for 33 years from Jerusalem, begged God to open his eyes, gal einai, so that he could unravel nifla’ot miToratecha, the wonders of God’s Torah (Psalms 119:18). Gal (גל), that term for unraveling the secrets of Torah, has a value of 33.

First, the number 33 plays an important role in mysticism. It represents the process of spiritual ascent. This is mirrored biologically in the fact that a newborn child has 33 bones on the vertebrae. There are 33 rungs from the bottom tip of the torso—a place of waste and excretion—up to the brain, the seat of the neshamah. As a person grows, the 33 bones fuse into 26, the value of God’s Ineffable Name. This is meant to signify, among other things, that one’s growth through life should be about attaining understanding of, and unity with, God. The purpose of the 33 is to reveal the wisdom of the 26. King David, who reigned for 33 years from Jerusalem, begged God to open his eyes, gal einai, so that he could unravel nifla’ot miToratecha, the wonders of God’s Torah (Psalms 119:18). Gal (גל), that term for unraveling the secrets of Torah, has a value of 33.

So, when Rashbi sought to reveal the secrets of Torah, he selected the 33rd day of the Omer. Moreover, in terms of the Sefirot of the Omer period, the 33rd day corresponds to Hod sh’b’Hod, “Splendour of Splendour”. Zohar itself means “radiance” or “splendour”. This was the ideal day to reveal the mystical light of the Torah. Finally, I believe Rashbi didn’t miss the fact that the 33rd day of the Omer is the 18th of Iyar, י״ח באייר, which is essentially an anagram of his own name, בר יוחאי!

Since ancient times, therefore, Jewish mystics would visit Rashbi’s tomb on Lag b’Omer. At some point in the 15th century (perhaps earlier), pilgrims that couldn’t reach Samuel’s Tomb at Givon went to Meron instead, knowing that others were journeying there around the same time. The fact that Lag b’Omer and Samuel’s yahrzeit are just ten days apart is no coincidence. And the same is true spiritually. What is the mystical connection between these days?

Rashbi and Yom Yerushalayim

On the 28th of Iyar, 5727 (June 7th, 1967), the IDF liberated and reunified Jerusalem during the Six-Day War. They subsequently liberated the rest of Judea and Samaria, the ancient heartland of the Jewish people. For the first time in two millennia, Jews had full access and control to their holiest sites, including Samuel’s Tomb. (Unfortunately, some of that control was subsequently given away by the politicians.) It is therefore most fitting that Samuel’s yahrzeit also became the day that the IDF liberated his tomb!

It has already been explained before (as Rabbi Ari D. Kahn does here, for instance) why the connection between the yahrzeit of Samuel and Yom Yerushalayim is significant. After all, it is Samuel that anointed Israel’s first kings including, most importantly, King David, who went on to lay the foundations of Jerusalem. Jerusalem is the “City of David”, the seat of the Davidic dynasty. It became the eternal capital of Israel. It is mentioned in the Tanakh more than any other place, nearly 700 times. It is the place to which we have faithfully faced over the course of three millennia of prayers. It was Samuel’s foundational work, more than any other, that led to the establishment of Jerusalem, so his day became Yom Yerushalayim. But what does this have to do with Rashbi?

We have already noted how the Zohar transformed every aspect of Judaism. It launched movements that resurrected the Jewish people and faith at least twice. And there is one more key development that came out of the Zohar: the quest for Redemption. In fact, one of the key goals of the Zohar is to hasten the Final Redemption. This is done through the path of rectification, and through the study of the Zohar itself. (For example, Zohar III, 124b, Ra’aya Mehemna, states that “…Israel shall taste of the ‘Tree of Life’, which is this book of the Zohar, and by this means shall they go forth from the exile in mercy.”)

More forcefully, the Zohar states that Redemption will come when Israel, at least on some level, takes matters into their own hands. The Zohar encourages Jews to be less passive and more proactive about their own fate. This is not just on the personal level, but also on the national level. In several places, it encourages Jews to settle the Holy Land and rebuild their rightful inheritance. For instance, in one passage (Zohar I, 139a, Midrash haNe’elam), the Zohar says that first Jerusalem should be rebuilt, then more Jews will be inspired to come back, and only then will we have the End of Days and the eventual Resurrection of the Dead. It bases this on Psalm 147, which says that God will “rebuild Jerusalem, gather in the exiles of Israel; heal their broken hearts, and bind up their wounds.” The order is clear: rebuild, then gather in, then heal the world.

In part because of this, many of the great kabbalists in history sought to settle in the Holy Land and worked hard to encourage others to do the same. This began with the Sephardis expelled from Spain, many of whom settled in Israel and rebuilt ancient towns. Already then, in the 16th century, they sought to re-establish a Jewish state, and actually got quite far, with Don Joseph Nasi being given a charter from the Ottomans along with the title of “Lord of Tiberias”. It continued with the mystics from Europe, both Hasidim (such as Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk, who led a large group of settlers) and non-Hasidim (such as Menachem Mendel of Shklov, a disciple of the Vilna Gaon). Of this we wrote in depth previously (see ‘The Kabbalah of Yom Ha’Atzmaut’). Finally, the Zionist movement itself was inspired, indirectly, by the Zohar. As outlined here, it was Rabbi Yehuda Alkali who published the manual for re-establishing a Jewish state that ended up in the hands of Theodor Herzl. It was Rabbi Alkali who established the Society for the Settlement of Eretz Yisrael in 1840, or 5600, the very year the Zohar had prophesied as the final possible starting point for the Redemption.

Therefore, it was really the Zohar that launched the original “settlement” movement. Without it—without Rashbi—the past few centuries would have played out very differently. Interestingly, it was a group of religious Jews back in 1886 that laid the foundations for a town around Samuel’s Tomb. That town didn’t last, and was later occupied by the Jordanians following the Independence War. The area was liberated in 1967 during the Six-Day War, which sparked a new “settler” movement. (The miraculous Six-Day War has also been credited with launching the modern Ba’al Teshuva movement, having inspired so many Jews.) Ten years later, Givat Ze’ev was established around Samuel Tomb by a new generation of “settlers”, and is now a thriving community. Fittingly, the 28th of Iyar, according to the Sefirot of the Omer, corresponds to Chessed sh’b’Malkhut, “Kindness in Kingdom”. It is a spiritual gate that opens blessings especially for rebuilding God’s everlasting kingdom.

The seeds of all of this were planted by Rashbi nearly two thousand years ago, after a devastating catastrophe in which the Romans slaughtered countless Jews, hunted down rabbis, destroyed Jerusalem again, then renamed Judea to “Palestine” in an attempt to wipe out the memory of the Jews for good. Rashbi survived those Romans, and revealed precisely what was needed to reverse all that they did, including the ultimate rebuilding of Jerusalem, and all of Israel with it. Therein lies the hidden connection between Lag b’Omer and Yom Yerushalayim.

Pingback: The Zohar Prophecy of the Six-Day War | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Physical Blemishes & Spiritual Heights | Mayim Achronim